I’m back from a brief visit to the wonderful island of Shiraishi. I don’t know how many times I’ve been round the island, but I do know that each time I wander about I always find something new and intriguing. This time it was the shrines to the side of the Shingon temple, another graphic illustration of shinbutsu shugyo (Shinto-Buddhist syncretism). I’ll write of them in a separate entry, but for the moment I want to strike a seasonal note with some more extracts from my long haibun (essay with haiku).

The autumnal tone is apposite, as I learnt to my shock that the population which had been 740 when I wrote my haibun six years ago has sunk as low as 625. It’s an alarming loss, and one that’s mirrored in many of the rural communities of Japan. Moreover, at least 60% of the population are aged over 60 years of age. Desolate shrines, diminished festivals, dejected kami is one of the effects as traditions come to the end of the line. All things must pass, but one can’t help feeling some melancholic mono no aware at the prospect…

(The full haibun can be seen here, and information about Shiraishi here.)

******************************************************************************

Autumn drew me back to spring discoveries. Retracing half-forgotten paths, I found the views had not changed, and the rocks looked like familiar old friends. Yet everywhere nature showed signs of winding down. A dead snake, drowsy wasps, mosquitoes too torpid to evade a casual swat. No caterpillar visitors now, barely any butterflies.

There was warmth in the greetings of human friends. These included the folk at the island’s sole café-bar and the delightful Amy Chavez, a free spirit who settled on Shiraishi to become the resident gaijin. Freelance writer and entrepreneur, she had managed to set up a yearly cycle divided between island summer, Bali winter and visits back to the US. Many dream of such a life, but few are brave enough to carry it out.

By now the beach lay empty, abandoned by the summer frolickers, yet the clear October days were sensual and warm. Others seemed to enjoy them just as much as I did.

Autumn daze –

Even the bees

Are basking

I was upbeat at being back, and it was not long before I turned to untrodden ways. Like a magician’s pocket, the island seemed able to supply a never-ending series of surprises. Rocks perched on the top of ledges, threatening to topple over at a touch; a bamboo grove of delicate finery filtering rays of golden sunshine onto the darkened ground; a mysterious cave which once housed a ritual round stone. It seemed impossible such a small island could offer so much.

For the islanders the primary concern is self-sufficiency, and in the early mornings one would pass old women on the way to their allotments. These island folk are doughty souls. I once fell into conversation with a sprightly seventy-five year old and complimented him on his vigour. ‘That’s nothing. You see those two,’ he said pointing at a small fishing boat. ‘He’s eighty-six and she’s seventy-nine.’

For the islanders the primary concern is self-sufficiency, and in the early mornings one would pass old women on the way to their allotments. These island folk are doughty souls. I once fell into conversation with a sprightly seventy-five year old and complimented him on his vigour. ‘That’s nothing. You see those two,’ he said pointing at a small fishing boat. ‘He’s eighty-six and she’s seventy-nine.’

You could see the dogged diligence in the island gardens, all neat trimmed bushes and orderly plants in the bare ground. I had passed by in springtime but hadn’t taken the time to stop and stare. Now I delighted in the details. Here would be a bonsai, there a collection of chrysanthemum, and over there a spirit house. Round this corner a roof tile with a ferocious devil, round that one a twisted pine.

November drizzle —

The dozing cat

Opens one eye

Bit by bit, I was getting a grip on the island’s history. There were tombs and artifacts from prehistoric times. It was said that the brother of Emperor Jimmu had stayed here in the legendary sweep of the Yamato clan across the Inland Sea. The Shingon temple had been set up in 1183 to pacify the souls of those killed hereabouts during the Gempei Wars, and the harbour dated from Edo times when its construction served to reclaim land from the sea.

Autumn fruit - persimmon

Autumn flowers - cosmos

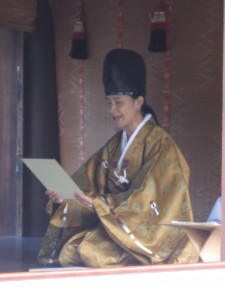

Manji applying some healing power.

At the temple’s autumn festival, which featured traditional dancing and the ceremonial burning of prayer sticks, I was given some protective healing by the island eccentric, Manji, using his ascetic powers. A cuddly uncle of a man, he lives in a dilapidated house by the harbour where he exhibits a display of kitsch such that one might take it for a junk shop. A friend to the wild life, he is followed wherever he goes by hungry birds, like a Japanese St. Francis. A friend to children too, he had once dressed up as Urashimataro, the Peach Boy, to welcome visitors to the island. The world needs more like him.

Falling leaves –

But you’re as chirpy

As a child

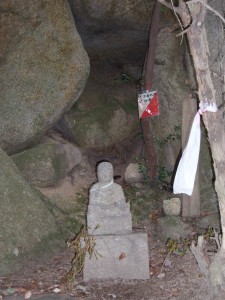

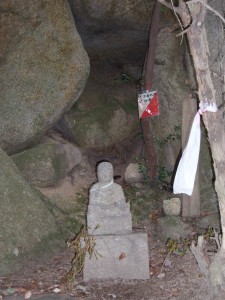

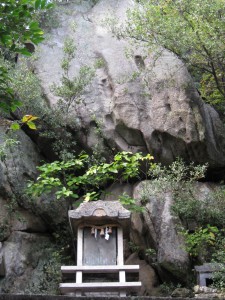

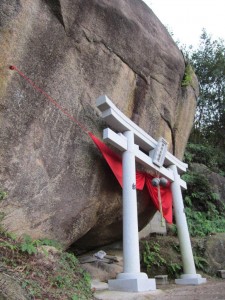

On my walks I had often come across small shrines and recognised them as part of a miniature ‘88 temple pilgimage’. Many of the Inland Sea islands have them because of their closeness to Shikoku, where Kukai (aka Kobo Daishi) had founded the original. I imagined the Shiraishi trail would take a few hours at most, like others I had walked. I was wrong. It takes two full days. Pretty amazing for an island that takes an hour and forty minutes to walk round.

The Edo-era follk who set up the route knew the topography well, for the small shrines are set with geomantic care in places with a numinous aura. Some are in the thick of groves, some on cliff edges overlooking the sea, and some in the clefts of enormous boulders. One even sits inside the ruin of a sixth-century tomb.

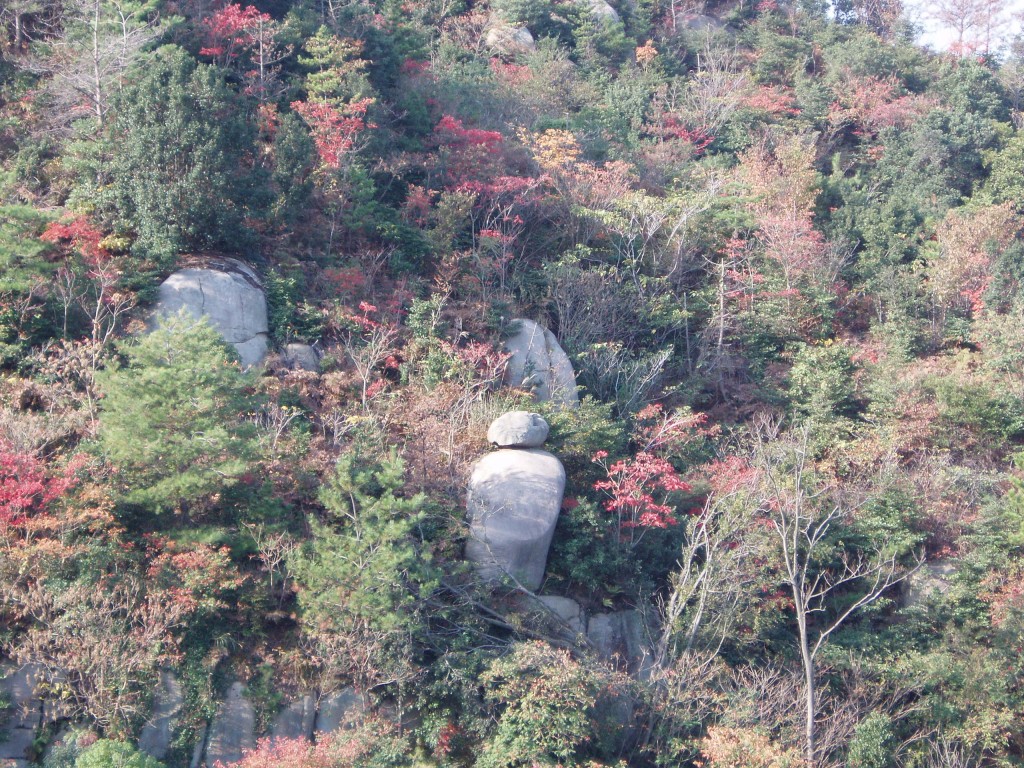

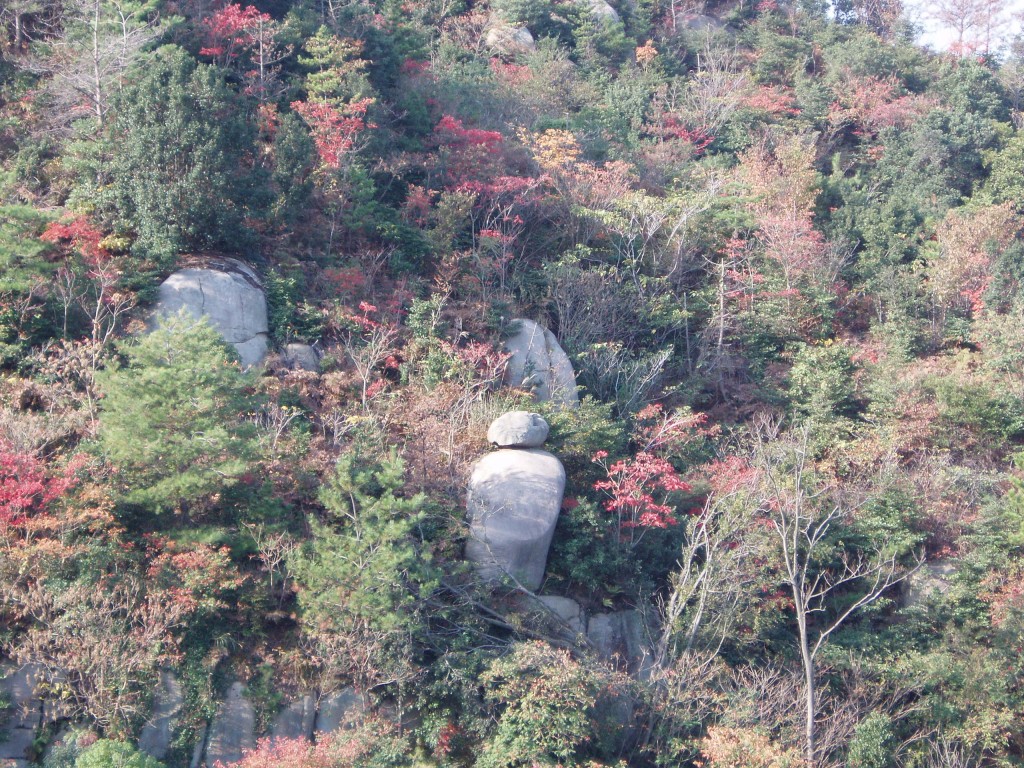

On a walk one day I had an unexpected surprise. Rounding a corner, I found myself faced with a hillside palette of multicoloured hues. There must have been something about the location that compelled the trees to dress up before their colleagues. It felt as if I’d stumbled on hidden treasure. No showy colours, no fiery red maples or bright gingko yellows, but subtle shadings woven into an evergreen background. Not a soul was to be seen: the picture was mine alone.

Autumn beauty —

The deafening silence

Of birdsong

With winter approaching, island life was winding down and it was getting time for me to leave. Morning walks had given way to afternoon strolls, and I spent the last few days walking the western side of the island to view the spectacular sunsets. Sometimes the beauty was so poignant that it tugged at the heartstrings.

A wintry chill –

Hard to hear the sound

Of the setting sun

Before I left, I revisited the table where I’d sat in the spring sunshine and written with such enthusiasm. There was little of the vibrancy that had been so evident before, only the persistent cawing of crows as they returned home. One group flew right across the face of the sun, black spots against the liquid orange, before heading for a small uninhabited island for the night. And as the fiery red glow spread slowly along the far horizon, the busy boats merged into darkness. My cycle of seasons had run its course.

Winter departure:

My heart reaching out

In its wake

For the islanders the primary concern is self-sufficiency, and in the early mornings one would pass old women on the way to their allotments. These island folk are doughty souls. I once fell into conversation with a sprightly seventy-five year old and complimented him on his vigour. ‘That’s nothing. You see those two,’ he said pointing at a small fishing boat. ‘He’s eighty-six and she’s seventy-nine.’

For the islanders the primary concern is self-sufficiency, and in the early mornings one would pass old women on the way to their allotments. These island folk are doughty souls. I once fell into conversation with a sprightly seventy-five year old and complimented him on his vigour. ‘That’s nothing. You see those two,’ he said pointing at a small fishing boat. ‘He’s eighty-six and she’s seventy-nine.’