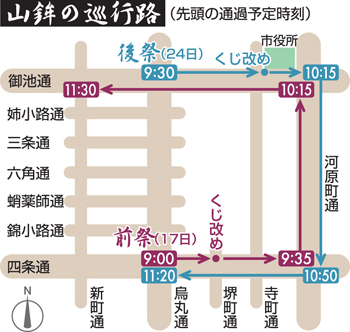

The floats with their tightly-packed musicians and gorgeous tapestries (some of Silk Road origins) are the highlight of the month-long festival. This year there are two parades, the Saki Matsuri with 24 floats and the Ato Matsuri (today) with 10 floats.

The Gion Matsuri is a complex month-long festival in Kyoto, with events spread out over the 30 days which are all directly related to this millennium-old event. In the grand parades there are 33 floats involved altogether, each with its own history, tradition and religious orientation. But there is far more to the festival than its main parade, and there have been significant amendments this year. The best single overview of it all can be found in the article below, courtesy of the Kyoto Visitors Guide (the page also has a full list of the month-long events).

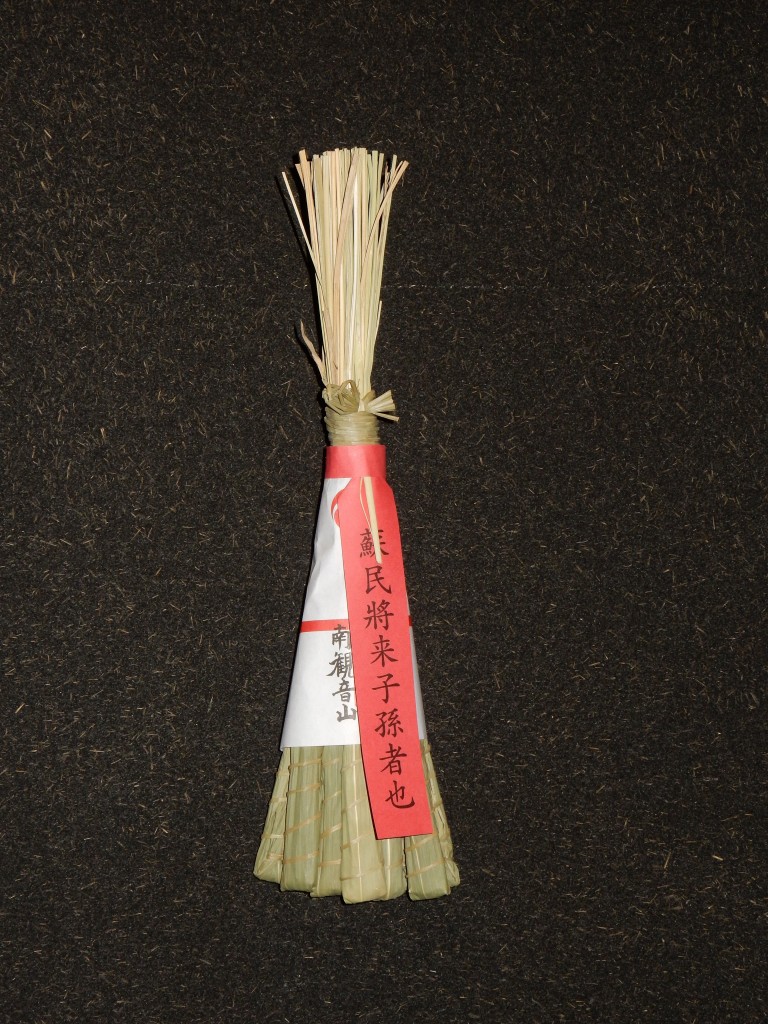

The chimaki charms for warding off pestilence and evil demons lie at the religious centre of the festival. Each float has its own version, and one is even edible!

Key points

* origins in 869 as a festival against pestilence

* 2 mikoshi processions, one from Yasaka Shrine to the resting place (otabisho); the other back again a week later

* 2 parades of floats, which take place in the mornings of the mikosi processions (July 17 and 24)

* On the evenings before the parades, floats are open to visitors and their treasures displayed

”””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””””’

Gion Matsuri by the Kyoto Visitors Guide

Gion Matsuri – synonymous to Kyoto’s summer, is Kyoto’s biggest and most important and one of Japan’s three largest festivals. The city of Kyoto becomes filled with the energy of people who have waited for this exact moment a year ago, except, this year things are going to change!

This year, exactly 48 years in history, the Gion Festival will return to its original form. The current united-procession will be again separated into the Saki Matsuri and the Ato Matsuri, and this means that the year 2014 will truly be special for everyone who witnesses and participates in this historic moment.

The Saki Matsuri, its style and schedules will basically stay the same, and the parade being gorgeous and boisterous with many floats as usual. In contrast, for the revived Ato Matsuri, it will be held in a much quieter atmosphere as there will be no stalls, nor extra goodies, etc. For tourists who can stay a bit longer, you may have a great chance to see the contrast of both the gorgeous and fun Saki Matsuri along with the solemn and beautiful Ato Matsuri like the light and shadow of the festival.

The ropework involved in the massive wooden floats is an example of immaculate Japanese craftsmanship (not a single nail is used).

History of Gion Matsuri

Throughout history, Japan has suffered many times from serious epidemics, floods, fires, earthquakes and recently tsunami. These were always viewed as signs that the ”gods” and ”goddesses” were not pleased. To appease the deities and pray for the deceased, rituals called goryo-e were held which over time, developed into festivals associated with a certain shrine. The Gion Matsuri, one of Japan’s oldest and largest goryo-e festivals, is dedicated to Yasaka Shrine (also known as the Gion Shrine).

The first goryo-e in Kyoto was held in 869 in response to a devastating plague. In desperation, the reigning emperor decreed that special prayers be recited at Yasaka Shrine. The prayers were successful and from then on were repeated any time the imperial capital was beset by a plague or natural disaster. This was how the Gion Festival came to be.

Though the festival began as a religious purification ritual, by the end of the Kamakura period (1185-1333) it had also become a way for certain craft guilds and kimono textile merchant families to show off their wealth and expertise.

From the late 16th century onwards, as a result of the growing prosperity of Kyoto’s textile merchants, textiles from China, Persia, and even Europe, imported via the Silk Road, were added to the floats. During the Edo period (1600-1868) and early Meiji period (1868-1912), the floats and the city of Kyoto were badly damaged by war fires on several occasions. However, each time the citizens worked hard to rebuild everything and the festival continued to grow in popularity and fame.

Floats offer different items for sale, with their stalls staffed by neighbourhood volunteers of all ages.

Behind the Scenes – Revival after almost half a century

In traditional Japanese festivals, people transfer the deity from one shrine to a special place during the festival, and then, return it to the original place as the festival ends. Therefore, two rituals are naturally very important: the one to welcome the deity and the other to return it to the original place.

The ritual to carry the deity out is called the Shinko-sai Festival while the one that returns the deity is called the Kanko-sai Festival. In the Gion Matsuri Festival, the Shinko-sai Festival is held on the 17th and the Kanko-sai Festival is on the 24th of July.

Gorgeously decorated floats were considered to be the preliminary celebration before the important mikoshi processions. Also, there is an important meaning to entertain the deity with beautiful crafts & treasures and with special kinds of festive music, to harmonize the religious solidarity and joyfulness together in this special occasion.

The float parade prior to the Shinko-sai Festival is called the Saki Matsuri (Preceding Festival) and the parade prior to the Kanko-sai Festival is called the Ato Matsuri (Later Festival). Hence, the original Gion Matsuri Festival used to have two float processions.

The backstreets of downtown Kyoto are illuminated for a few days by the bright lanterns of the floats

During Japan’s high economical growth period, the parade routes had to be changed due to increasing car traffic on roads, etc. In 1966, the Saki Matsuri and Ato Matsuri were merged and only one parade took place on July 17th until last year, 2013.

There are several reasons for the revival of the original festival this year, but one reason is that the voices on reviving the original festival have increased recently, to rethink and recognize the meaning of the Gion Festival once again.

A second reason is that the numbers of locals who knew and experienced the original festival held more than half a century ago are now slowly decreasing, and it is regarded as the best timing to return them while those locals are still able to share their advice to younger generations to inherit the festival’s traditions.

So this year, the Gion Matsuri Festival has returned to its original form. In order to succeed the tradition of the festival faithfully, two float parades will again commence. The original form of the festival that has existed for over 1000 years will return to the present-day, at last.

Some of the treasures displayed during the festival are exquisite works of art, such as this sliding screen by Maruyama Okyo from the late eighteenth century

By way of celebration, Japan Today carried a piece about a portable shrine being ferried across Matsushima Bay, north of Tokyo. It was part of the 67th Shiogama Port Festival in Shiogama City, Miyagi Prefecture. Two local mikoshi were paraded through the streets before being loaded aboard decorative boats and transported throughout the bay, accompanied by up to 100 fishing vessels.

By way of celebration, Japan Today carried a piece about a portable shrine being ferried across Matsushima Bay, north of Tokyo. It was part of the 67th Shiogama Port Festival in Shiogama City, Miyagi Prefecture. Two local mikoshi were paraded through the streets before being loaded aboard decorative boats and transported throughout the bay, accompanied by up to 100 fishing vessels.

It is believed that yabusame was first performed in the Usa region of Kyushu by order of Emperor Kimmei (509-571) at the site of Usa Shrine (the earliest Hachiman shrine in Japan) to pray for peace and abundant harvests. However, the first recorded yabusame performance was in 1096, for the retired Emperor Shirakawa. Hachiman is a popular deity who protects warriors, agriculture and generally looks after the well-being of the community.

It is believed that yabusame was first performed in the Usa region of Kyushu by order of Emperor Kimmei (509-571) at the site of Usa Shrine (the earliest Hachiman shrine in Japan) to pray for peace and abundant harvests. However, the first recorded yabusame performance was in 1096, for the retired Emperor Shirakawa. Hachiman is a popular deity who protects warriors, agriculture and generally looks after the well-being of the community. “Where is everybody today?” Angeles asks him. “Up at the shrine, for the ceremony,” he answers, nodding toward the hill over the road. Not wanting to miss out, we trot up to the shrine.

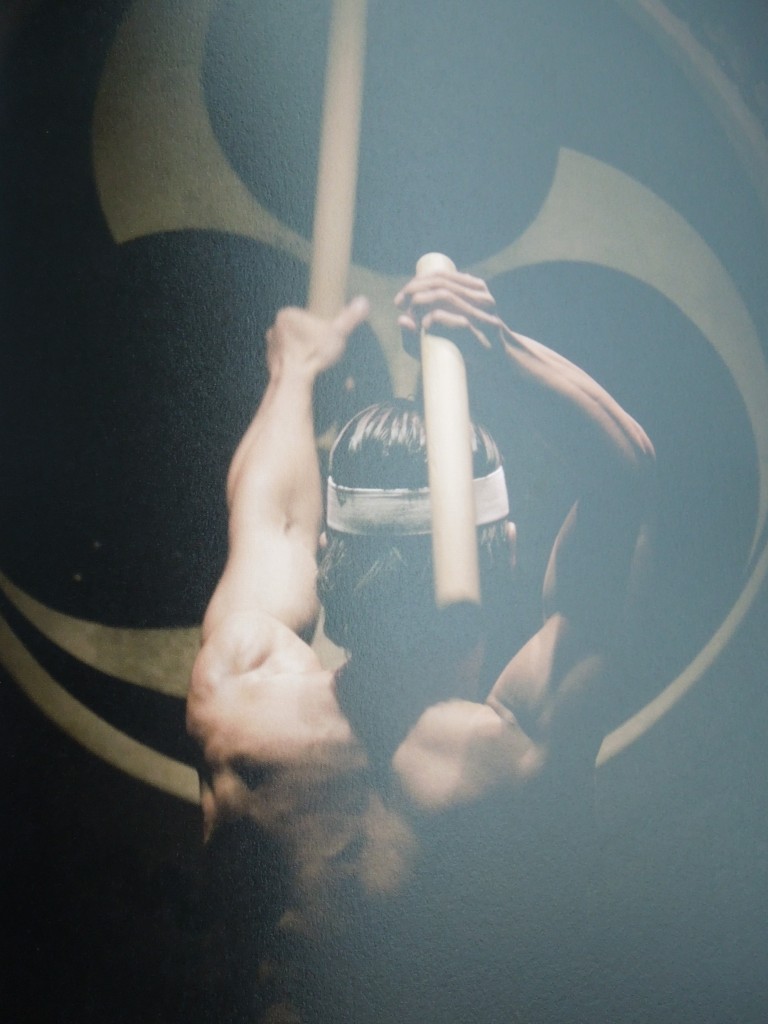

“Where is everybody today?” Angeles asks him. “Up at the shrine, for the ceremony,” he answers, nodding toward the hill over the road. Not wanting to miss out, we trot up to the shrine. Another rider joins the group: Toshie Aoshiba, a female of archetypal jockey build, no more than half the size of Susumu. Now comes a pivotal yabusame moment, as the rider places an arrow in his bow and pulls the bowstring taut. With a folded prayer-paper clenched between his teeth, he ceremoniously aims his arrow — first at the ground and then at the sky, to symbolize harmony between heaven and Earth — before firing the arrow off into the distant forest canopy. Enthusiastic applause ensues.

Another rider joins the group: Toshie Aoshiba, a female of archetypal jockey build, no more than half the size of Susumu. Now comes a pivotal yabusame moment, as the rider places an arrow in his bow and pulls the bowstring taut. With a folded prayer-paper clenched between his teeth, he ceremoniously aims his arrow — first at the ground and then at the sky, to symbolize harmony between heaven and Earth — before firing the arrow off into the distant forest canopy. Enthusiastic applause ensues.

Tosha says he achieves such intensity by using classical techniques as a base for his performances. Not solely focusing on the music, though, he also emphasizes visual presentation through dancing and dialogue. The result produces energetic moments that can just as easily slip into a moment of calm.

Tosha says he achieves such intensity by using classical techniques as a base for his performances. Not solely focusing on the music, though, he also emphasizes visual presentation through dancing and dialogue. The result produces energetic moments that can just as easily slip into a moment of calm.