A woman hugs a sacred tree at Kyoto's Seimei Jinja

In a sense, you could say that the whole notion of ‘power spots’ is a modern re-packaging of ancient notions, since many traditional sites were located in places felt to exude a certain ‘energy’. It explains why most of the modern power spots are in fact Shinto shrines, which were built in ancient times to honour the spirit of place.

There are something like 40 books on the subject in Japanese, including a whole series by Ehara Hiroyuki, a psychic who was promoted on television as a spiritual counsellor. The books are best-sellers but surprisingly do little more than list the traditional attributes of shrines like Shimogamo Jinja, saying what they are famous for and what the nearest eating places and tourist sights are.

Such is the attractiveness of power spots, though, that local authorities are keen to promote them for their tourist value. Green Shinto carried a piece before on Aomori’s promotion of its power spots. Now we have come across a listing of four Kyoto power spots: http://www.kyoto.travel/powerspots.html. It’s of interest because the page is in a sense official, run by the City of Kyoto and Kyoto Convention & Visitors Bureau.

I’m not sure how the officials selected the four power spots below, but the inclusion of Kiyomizu Temple at the expense of Shimogamo Jinja is a surprise, since the latter is widely known as ‘Kyoto’s power spot’. Standing at the confluence of two rivers with an ancient patch of woodland, the shrine reaches into the distant past before the city of Kyoto was ever thought of. It surely deserves inclusion!

*********************************************************

Kyoto’s Power Spots (spiritual spots)

Catching and drinking 'the magical waters' of Kiyomizu's original spring is popular with visitors

Worldwide attention is being drawn to power spots (spiritual spots), where one can obtain energy from the earth and nature. In this issue, we will introduce a number of Kyoto power spots.

Kurama

Since ancient times, Mount Kurama has been said to be the home of the spirits known as “tengu.” And it is also known, in recent years, as the birthplace of “reiki”.

The Kurama Temple was built on the mountain summit with Sonten (energy from the universe) as its major deity. The power from the universe is said to be particularly concentrated in the center of the six-pointed star located in front of the main sanctuary.

Kifune

Mount Kifune is located right next to Mount Kurama. It is a place where pure water flows from the well.

The Kifune Shrine was built as the place to offer prayers to the deity of water, and it has attracted believers since ancient times. The sacred water that flows abundantly from the stone wall is said to have a unique and high undulation property, so try drinking a mouthful and feel its pure energy.

It is only at this shrine that the words float up to the surface of the paper when a “water fortune telling card” touches this water.

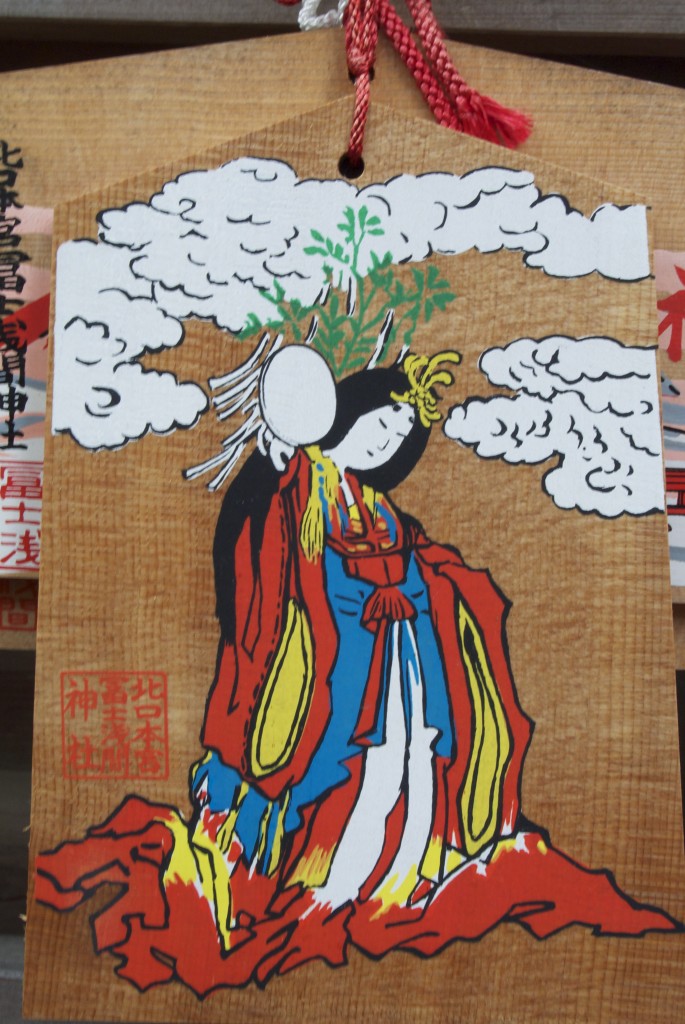

Seimei Shrine

Here fortune-telling is carried out through use of astrology (tenmondo) and other methods. This shrine is dedicated to the alchemist/fortune-teller Seimei Abe who lived one thousand years ago and was famous for his manipulation of spiritual power. It has gained fame for assisting in avoiding disasters and for curing illnesses and wounds, and even today, the ruins of Seimei Abe’s residence over which the shrine is built is famed as a power spot.

Kiyomizu Temple

Kiyomizu Temple has been designated a world heritage treasure and it is one of Kyoto’s major temples.

“Kiyomizu” means ‘beautiful water,’ and it was due to the discovery of the spiritual water at this site that the temple was built in this spot. If you drink from the “Otowa Waterfall” located in the temple precincts, it is said that your prayers for health and long life will be answered.

Kifune's popularity has shot up since it became recognised as a 'power spot'

People line up to pray on Kurama's 'power spot' in front of the temple