There is a long article on a website entitled Hemp Culture in Japan by David Olsen, which covers the plant’s many connections with traditional culture. Though the author is evidently not an expert on Shinto, he does make reference to a large number of books, as can be seen in the extract below from the full-length piece. (For those wishing to read the whole piece or follow up on the book references, please click here.) It’s worth noting that hemp is a variant of the cannabis plant; marijuana is a different variant.

******************************************************

Hemp Culture in Japan by David Olsen

Hemp was already a well-established crop by the time written language and recorded history appear during the Yayoi Period. The indigenous Ainu on the northern island of Hokkaido made their colorful costumes from hemp fiber during this period, circa the 3rd century AD (Constantine 1992). These people lived in patriarchal clan groups and wore clothes of hemp and bark. Also, the complex Shinto system of multiple patriarchal deities developed as numerous clans each adopted a patron saint. (Hooker 1996)

Hemp field in France (courtesy Wikicommons)

A few centuries later, Bukkyo (Buddhism) made a similar journey starting from India across the Himalayas to China, on to the Hermit Kingdom of Korea, and ending up in Japan. In the long migration from India to China, the teachings of the Buddha were modified. However, from China to Korea, the basic tenets remained unchanged.

Upon arriving to Japan however, the natives adapted and intertwined Buddhism with both the traditional mythological religion of Shinto and their reverence for hemp. Shinto is the ancient ‘way of the gods’, a ritualistic expression of profound respect for the kami (the intrinsic god-like spirit) in nature. Purity and fertility are held paramount, and hemp is considered a symbol of both.

The Kojiki (the native chronicle of Japan) relates that after creating Japan, the ‘primal pair’ [Izanagi and Izanami] consulted each other saying, “We have now produced the great eight-island country, with the mountains, rivers, herbs and trees. Why should we not produce someone who shall be lord of the universe.” (Moore 1991) This pair then begot the founding goddess-figure, Amaterasu Omikami (sun goddess) who is enshrined at Ise.

The prayer recited at the shrine is called Taima (hemp) [Jingu taima refers in fact to the Ise amulet]. Hemp [seed], salt and rice are the sacred staples that are used as part of all the rites at the shrine (Yamada 1995). The emperor himself is regarded as a direct descendant of these gods and acts as the high priest of the folkloric Shinto belief.

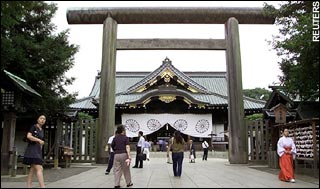

“At Shinto jinja (shrines) and Buddhist tera (temples), certain objects are symbolically made from hemp. For example, the leg-thick bell ropes, and the noren, a short curtain that hangs over the doorways and brushes the top of the head as one enters the room, must be hempen. The noren acts as a symbolic purification rite, meant to cause evil spirits to flee from the body.” (Robinson 1996)

Indeed, the Shinto priests and faithful used hemp fibers as symbolic elements in their religious ceremonies. One such use was the waving of a gohei (a short stick) with undyed hemp fibers attached to the end. Shaking these asa fibers above the patron’s heads apparently drove the evil spirits from the soul. Further, hemp was a symbolic gift of acceptance and obedience from the groom’s family to the bride’s in times of matrimony (Robinson 1996).

Historically, the priests dressed in hemp robes as well. It is in death that Shinto and Buddhism blend into a common braid. The relatives continue to visit the graves, leaving offerings and praying in the Buddhist way. Yet at home, a family shrine with the departed’s picture and memorabilia is tended in the Shinto tradition with hand claps, incense, and worshipping of the kami (deity) within.

The Japanese traveled long distances searching for salt, seeking enlightenment and following pilgrimages. In olden times, these merchants, wandering pilgrims and traveling believers were obliged to leave an offering to the sahe no kami (protective deities) before embarking on a journey. “These deities were represented by phalli, often of gigantic size, which were set up along highways, and especially at cross-roads, to bar passage of malignant beings who sought to pass . . . Standing as they did on the roadside and at cross-roads, these gods became the protectors of the wayfarers; travelers prayed to them before setting out on a journey and made a little offering of hemp leaves and rice to each one they passed.”(Moore 1991)

Hemp has various practical uses, including string and clothing (courtesy Rakuten)

In another old tradition, rooms of worship were purified by burning hemp leaves by the entrance. This would invite the spirits of the departed, purify the room and encourage people to dance. “On the first evening, fires of hemp leaves are lighted be-fore the entrance of the house, and incense strewed on the coals, as an invitation to the spirits. At the end of the three days, the food that has been set out for the spirits is wrapped up in mats and thrown into a river. Dances of a peculiar kind are a conspicuous feature of the celebration, which is evidently an old Japanese custom; the Buddhist elements are adscititious (derived from outside).” (Moore 1991).

This ritual took place as part of a Buddhist holy day for “giving respect and making amends with departed ancestors”. The current tradition at this August Obon festival involves the similar practice of leaving offerings of the departed’s favorite foods on the grave, perhaps to purify or satisfy the restless soul. At some time in the past, hemp leaves were likely a part of this ritual as well.

Zen (the meditative Taoist-influenced branch of Buddhism) was especially influenced by hemp. Samurai (elite warriors) and scholars who followed the subtle tenets of Zen express hemp’s inspiration in arts like haiku (short poems), aikido (a martial art), kyudo (archery) and chanoyu (tea ceremony).

A well-known children’s adventure story tells about a technique used by ninja (warriors) to improve jumping skills. The student ninja plants a batch of hemp when he begins training and endeavors to leap over it every day. At first this is no challenge, but the hemp grows quickly everyday and so does the diligent ninja’s jumping ability. By the end of the season, the warrior can clear the 3-4 meter high hemp. This certainly attests as much for hemp’s vitality as the ninja’s ability (Mayuzumi 1996, Masuda 1996).

The formal dress of the Samurai warriors was hempen as were the training clothes of meditators and martial artists. In kyudo (archery) the bow’s string is specifically hemp, which reflects a connection with the meditative practice of Zen as well as hemp’s toughness as a fiber (Mayuzumi 1996).

In an elaborate, pre-bout ceremony called dohyo-iri, the reigning Sumo wrestling grand champion Yokuzuma carries a giant hemp rope around his ample girth to purify the ring and exorcise the evil spirits. This continues even today, as the belt worn by Hawaiian-born champion Akebono is also made of hemp (Wein 1996-97).

Sumo champion Akebono doing the 'dohyo-iri' ritual (courtesy chijanofuji)

Hemp is also being grown in Nagano Prefecture for making the bell ropes, curtains and other essential goods for Shinto and Buddhist houses of worship (Maeda 1995). In this area, the hemp tradition lives on in festivals and dance. The Japan National Tourist Organization tells about this in their on-line brochure:

“Oasahiko Shrine: Just walking to this quiet shrine is a lovely experience. On either side of the road are 400 to 500-year-old black pines designated a Prefectural Natural Monument. Several wonderful festivals are held here: . . . a lion dance (shishi mai) in November to honor the god who brought hemp and cotton to the province . . .”

On the smallest of the four main Japanese islands (Shikoku) hemp is grown for the use of the imperial family. When Emperor Hirohito died in 1989, a coronation was held for his heir. Since Hirohito’s son was succeeding him as the ‘living entity of God’, there was to be a special Shinto ritual. In Shinto beliefs, hemp symbolizes purity, and the new emperor was bound by tradition to wear hemp garments, which had become unavailable over the course of his father’s long rule.

When a new Emperor ascends the throne in Japan, specific symbolic rituals and ceremonies usher in the passing into the new era. Even the years in modern times are measured by the Emperor’s years of reign, indeed history is divided into eras of rulers. As hemp is a symbol of purity in the Shinto tradition, the Emperor wears hemp robes for many of the ceremonies. The principal ceremony is called “Great rice offering” and while the details are a secret, there must be a roll of hemp waiting at the foot of the royal futon at the end of the day.

Since the last occurrence (pre W. W. II, Emperor Hirohito), hemp had been criminalized. A group of Shinto farmers in Tokushima-ken had thought ahead, planted a symbolic yet illegal crop, and presented the emperor with his new clothes made of pure local hemp (Gruett 1994, Bennet 1997). They are still producing this hemp crop for the exclusive use of the imperial family.

In the village of Koyadaira-mura and Yamakawa-cho town, the country people spun and wove the cloth into the sacred fabric called “aratae” (fine cloth) 13 meters long and 34 centimeters wide. The villagers presented it to the Imperial family so the ritual could go on (Bennet 1997). These farmers were rewarded for their efforts and continue to cultivate pure hemp exclusively for the Imperial family on their semi-tropical island between the “Seto-kai” (Inland sea) and the Pacific Ocean.

Household accessories such as washcloths and curtains continue to be sold, but are made from Chinese and Korean hemp. More recently, new hemp products from Western hemp manufacturers are taking off … Some Japanese realize this is an indirect trade.

“The struggle to liberate and revive hemp is therefore a struggle to renew Japanese culture and liberate the country from the occupation policies and colonial subjugation of the United States. Speaking spiritually, I believe this struggle is every bit as important as the movement in Okinawa today for the removal of the American bases. We are talking about physical and spiritual independence.” (Yamada 1995)

The national government also continues to maintain its own seed reserves. Since 1946, when Cannabis hemp was in short supply due to the war, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government Medicinal Plant Garden has maintained a seed stock and bred varieties of asa for research at a large secure complex in suburban Tokyo. Given the Japanese knack for detail and research, it is certainly a valuable cache of information and genetics. The director, Torao Shimizu, maintains that the plants are just to teach people what hemp looks like so they can dispose of it should it be found it growing in their area (Lazarus 1994). While the original intent seems to have been for medicinal use of Cannabis, this motive has been lost under a cloud of paranoia, though the use of seeds for medicine is common information. “The seeds are used as bird seed and can also be used as a medicine (asashijingan), as a mild laxative” (Kojien 1991, Wein 1997).

***********************************************

For a piece on Japan’s 2nd Annual Hemp Festival, please click here.

The clear link between foxes and Inari is documented in Edo Period illustrated works, in which there are depictions of “fox weddings” with humanized foxes going through weddings. In Kudamatsu, Yamaguchi Prefecture, in the Inari festival held on November 3 every year, there is a re-enactment of a wedding between foxes.

The clear link between foxes and Inari is documented in Edo Period illustrated works, in which there are depictions of “fox weddings” with humanized foxes going through weddings. In Kudamatsu, Yamaguchi Prefecture, in the Inari festival held on November 3 every year, there is a re-enactment of a wedding between foxes. A 2011 study, published in the Journal of Cosmology, reviews the “evidence associated with the fox representations [and] argues that the beginnings of hierarchy in Andean South America occurred with the rise of a priestly cult who maintained a complex knowledge of astronomy.” The article entitled “Ancient South American Cosmology: Four Thousand Years of the Myth of the Fox”, states:

A 2011 study, published in the Journal of Cosmology, reviews the “evidence associated with the fox representations [and] argues that the beginnings of hierarchy in Andean South America occurred with the rise of a priestly cult who maintained a complex knowledge of astronomy.” The article entitled “Ancient South American Cosmology: Four Thousand Years of the Myth of the Fox”, states: Shapeshifters, a separate Indo-European or Indo-Iranian development

Shapeshifters, a separate Indo-European or Indo-Iranian development

Green Shinto is privileged to carry this piece by Pat Ormsby, a licensed priest with Kompira Shrine. Resident in the environs of Mt Fuji, she has written previously about the

Green Shinto is privileged to carry this piece by Pat Ormsby, a licensed priest with Kompira Shrine. Resident in the environs of Mt Fuji, she has written previously about the