“In recent decades, debates have erupted and intensified about the relationships between religions, cultures, and the earth’s living systems. Some scholars have argued that ritual and religion can play a salutary role in helping humans regulate natural systems in ecologically sustainable ways. Others have blamed one or more religions, or religion in general, for promoting worldviews and cultures that precipitate environmental damage. Religious production in recent years suggests not only that many religions are becoming more environmentally friendly but also that a kind of civic planetary earth religion may be evolving. Examples of such novel, nature-related religious production allow us to ponder whether, and if so in what ways, the future of religion may be green.”

So runs the abstract for a paper entitled ‘A green future for religion’ by Bron R. Taylor. I must confess my interest was aroused by the notion of a ‘civic planetary earth religion’. Yes, please…

For the moment it’s of more than passing interest to witness the ‘greening’ of religions as the environmental crisis deepens. Even the Pope has been showing green credentials.

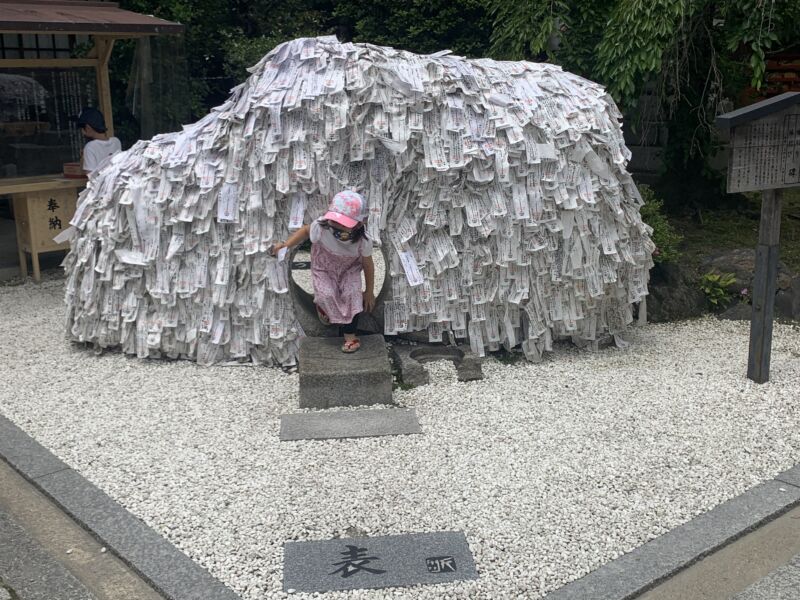

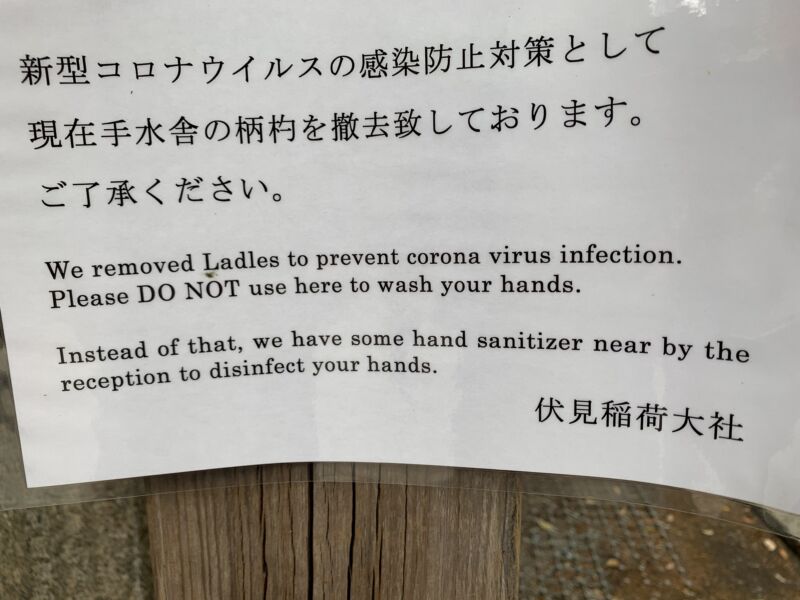

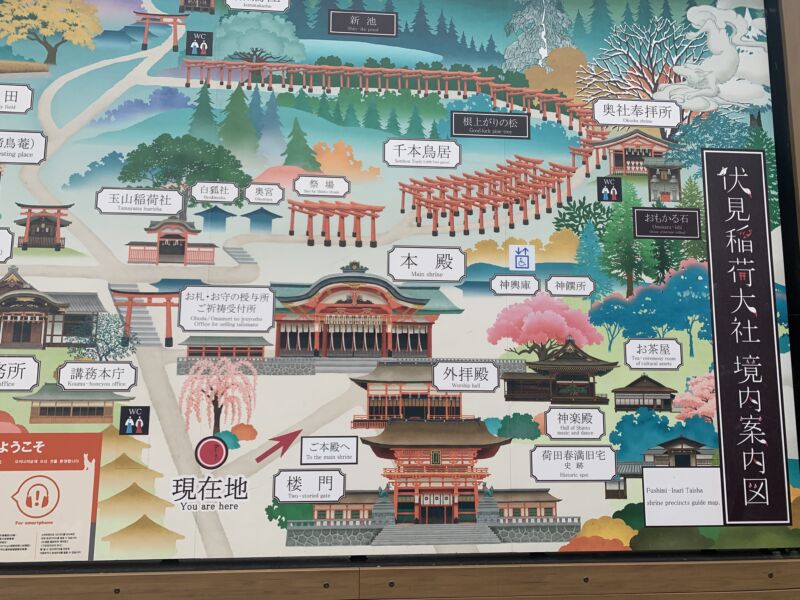

A striking example of a Shinto outreach to the green movement is currently being displayed in California with the recent establishment of the Shinto Shrine of Shusse Inari. The head priest has been pushing the environmental potential inherent in Shinto with slogans such as ‘Passing along eco-conscious traditions to the next generation’.

It takes courage to be a pioneer ahead of the game, and our respect goes out to Rev. Izumi Hasegawa for her trail-blazing activities. As a resident of Los Angeles, she is undertaking a daunting task in setting up a Shinto shrine with English outreach to the local population, yet thanks to her hard efforts she is managing to succeed against the odds.

Indicative of Hasegawa-san’s resolute and innovative spirit is the live stream of Shinto services she is offering, one of which will be starting on youtube even as this article is being written. It’s a Summer Blessing ‘to show respect and appreciation to the nature spirits and asking for blessings’. Here is part of the publicity for the event, which shows a revisioning of Shinto along pan-national and environmental lines.

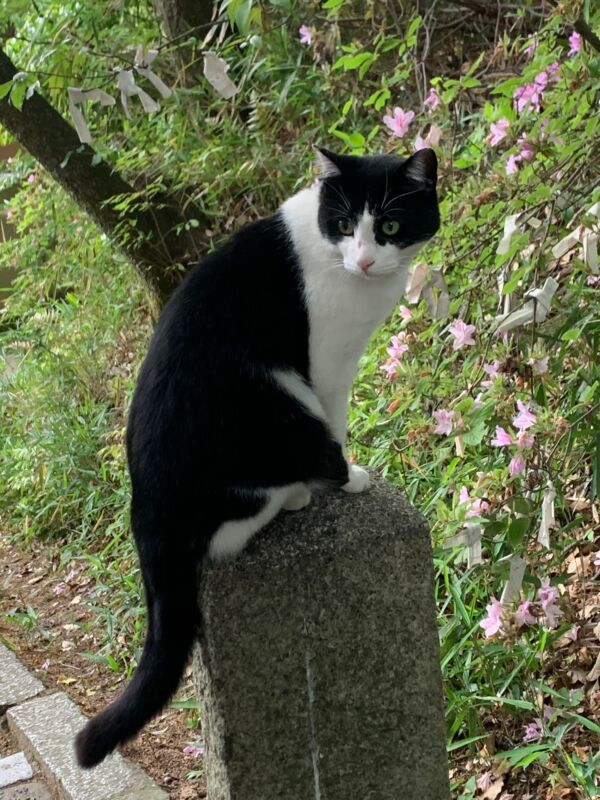

Shinto is a mindset and way of living with respect for nature, living things and our ancestors, and it has long been recognized as Japan’s cultural root. Unlike Buddhism, Christianity, or other religions, Shinto has no holy texts, and there is no individual founder. It is said that Shinto has been practiced for more than 2,000 years.

One of the most important elements of Shinto is paying respect and seeking harmony between people and nature, among our families, communities, and the world. In today’s society, the need to strive for these goals has become more apparent than ever before.

We hold various events introducing the traditional Japanese eco-conscious way of life so that future generations can enjoy nature as we do. Details about Shinto and these events can be found on our Newsletter, website, and social media.

Please join and enjoy our events!!

May the Nature Spirits/Kami-sama be with you!

Stay safe and be well!

Rev. Izumi Hasegawa

Shinto Shrine of Shusse Inari in America

www.ShintoInari.org

Instagram @ShintoInari

Facebook@ShintoInari

Twitter@ShintoInari

YouTube ShintoInari

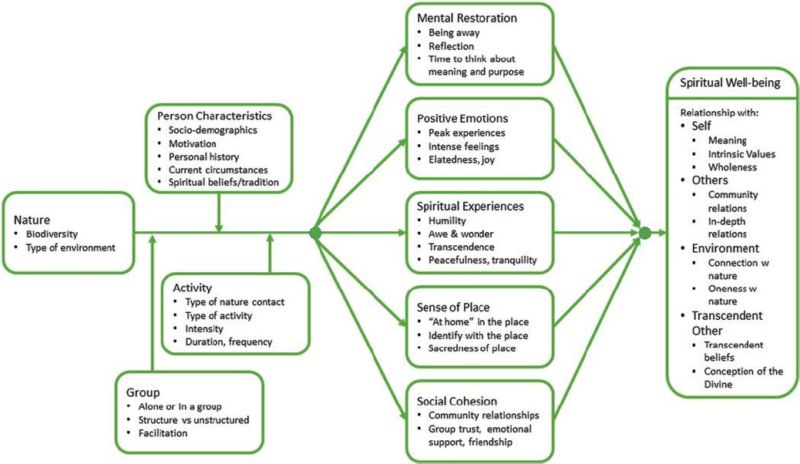

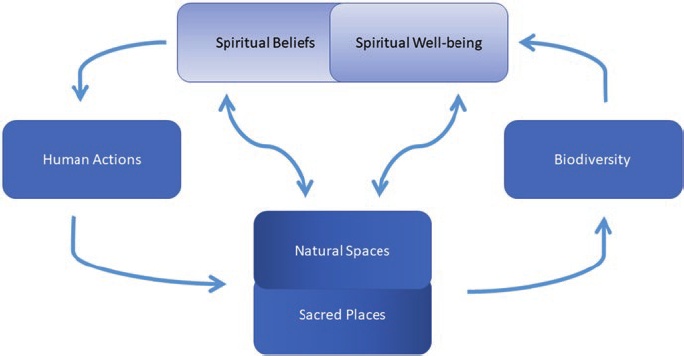

Biodiversity and Spiritual Well-being

Biodiversity and Spiritual Well-being