The following is taken from an academic paper entitled Power Spots and the Charged Landscape of Shinto by Caleb Carter, assistant professor at Kyushu University. First published in the Japanese Journal of Religious Studies in 2018, the article considers the popularity of the ‘power spot’ phenomenon contrasted with the scepticism of the Jinja Honcho orthodoxy. I think it’s fair to say that Togakushi Shrine is a shining example of Shinto’s sacralisation of nature, surrounded by woods and lush greenery fed by sparkling streams.

*****************

Togakushi Jinja offers one example of a Shinto site that has been recently reinterpreted as a power spot. Situated in the mountains of northern Nagano Prefecture, the shrines lie just to the southwest of the jagged ridgeline of the peak bearing the site’s name. There are five shrines in total, three of which are fully staffed and operational. In the Edo period, Togakushi served as a jikimatsu of the Tendai institution, placing it directly under the head temple of Kan’eiji (in Edo). It was staffed by fifty-three cloisters and managed by a chief administrator who was dispatched from either Kan’eiji or Hieizan. At the start of the Meiji period, the Tendai priests and yamabushi (practitioners of Shugendo) of the site were compelled under government directives to cease all Buddhist activities and convert to Shinto or change professions.

The newly designated shrines joined the nascent, state-sanctioned order of Shinto and were classified as kokuhei shōsha, a distinguished rank that implied the site’s allegiance and tribute to the emperor and country. Today, Togakushi remains a Shinto site and is affiliated with Jinja Honchō, though there is an active interest among its clergy to revive aspects of its historical roots in Buddhist-Shinto-Shugendo combinatory practices.

Its reputation as a power spot has drawn many new outside visitors. According to residents with whom I spoke, this began with Ehara Hiroyuki, who published an extensive account of his visit to Togakushi in 2006 in his Spiritual Sanctuary series, claiming it to be a “sacred place of overwhelming power” with “especially high levels of energy”. Since Ehara’s endorsement, the number of visitors to Togakushi has steadily increased. While there was no significant jump directly following his visit, prefectural statistics show that the annual average of 1 million visitors to the region rose to 1.2 million in 2010 and again to 1.6 million in 2015 and 2016.

While a variety of factors account for this increase (including the Ancient Shinto trend), Togakushi’s notoriety as a power spot remains a major influence. Visitors drawn by this recent designation carry out many of the practices typical of those at an ordinary shrine, making it difficult, if not problematic, to distinguish between types of patronage.

Power spot enthusiasts continue to pray and make offerings at each haiden, talk about the kami, and observe general shrine etiquette. Nevertheless, certain patterns in behavior and language suggest common orientations in the power spot phenomenon. It is first evident in the heightened level of attention and reverence paid to particular natural objects like trees, stones, and waterfalls.

While the entire region of Togakushi is often said to be a power spot, a number of tall cedars and a small waterfall next to the main shrine of Chūsha stand out as especially popular. These objects have long been designated as sacred by the shrine (evident in the shimenawa ropes and shide strips of paper demarcating them), but their new designation has elevated their status among visitors.

Following prayers at Chūsha, visitors often stand before the waterfall, sometimes with palms facing outward. Many also lay their hands on the trunks of the large trees. I was told by older residents that this practice dates back as far as they can recall but that it has substantially increased under the power spot phenomenon. As for the basis of this power, visitors often describe it simply as an “energy” (enerugi ) that facilitates rejuvenation, purification, and healing. It is sometimes associated with the kami but more often attributed broadly to the earth and surrounding natural elements.

If visitors to Togakushi are entranced by the idea of the shrine’s qualities as a power spot, priests and residents of the village do not appear particularly perturbed by it. One male priest in his sixties reasoned that if one understands the kami as a source of power, the notion of Togakushi as a power spot is entirely conducive. The site, after all, is endowed with many local deities. Another priest (a man in his eighties) took a similar stance: as a local historian of Togakushi, he found the idea consistent with historical views of the mountain as a place of numinous power.

Nonclerical residents similarly associated this power with the kami or, more broadly, the natural landscape. There is also a positive economic side to the site’s new reputation. Like many rural communities, Togakushi Village has long struggled with a decreasing population and an aging community. Aiming to stave off further decline, regional municipalities around the country have been enacting policies, toted as gurīn tsūrizumu (green tourism), since the 1990s that promote domestic tourism. The issue became a national priority in 2008 under the newly conceived Japan Tourism Agency.

Togakushi residents themselves have long been aware of these downward trends. The new reputation of their shrines is welcomed by many. The Toga-kushi Tourism Association has made power spot pilgrimage a centerpiece of its campaigning efforts. In 2017 it promoted taxi tours featuring the region’s power spots on its official website. Users of the website could book a tour of Zenkōji, Togakushi, and nearby Akakura Onsen that combined cuisine, hot springs, and “encounters with the power of the gods” (kami no pawā o fureru). The Togakushi portion included access to all five shrines along with a lunch of soba noodles (the area’s famous dish) at one of the village’s restaurants.

Apart from the activities of the Tourism Association, local business owners have taken individual initiative.The façade of one gift shop just outside the torii at Chūsha was plastered with signs advertising “power stones” (pawāsutōn ) when I visited in 2015. As residents themselves, the priests also benefit from the overall uptick in tourism. Many of them are inn proprietors, descending from families who historically operated shukubō, or lodges that hosted confraternities (kō) centered on the worship of Togakushi’s buddhas, bodhisattvas, and local deities. With that baseline of support steadily shrinking, most have now opened their establishments to the public as inns. The rise in new visitors has, no doubt, helped to fill more rooms, as one priest informed me. It should be noted that the reception by priests to the notion of Togakushi as a power spot should be interpreted as a private view. The shrines do not overtly endorse the idea.

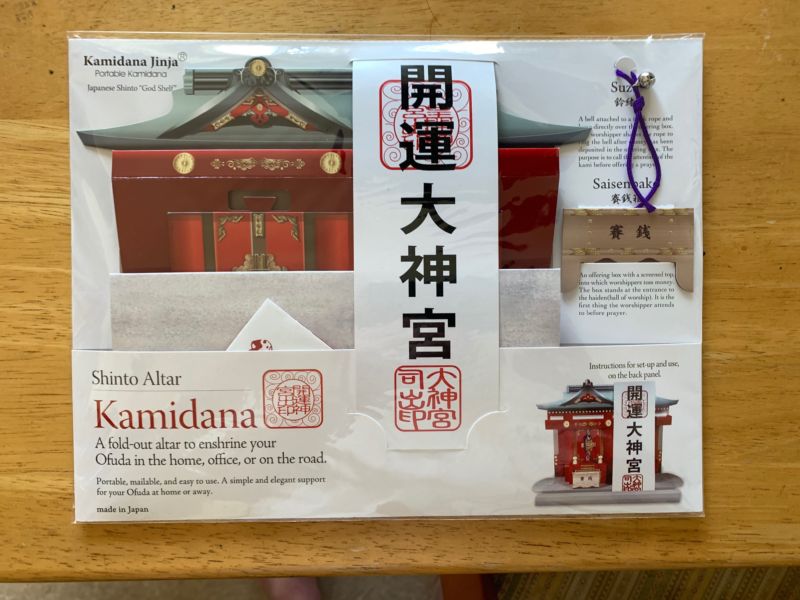

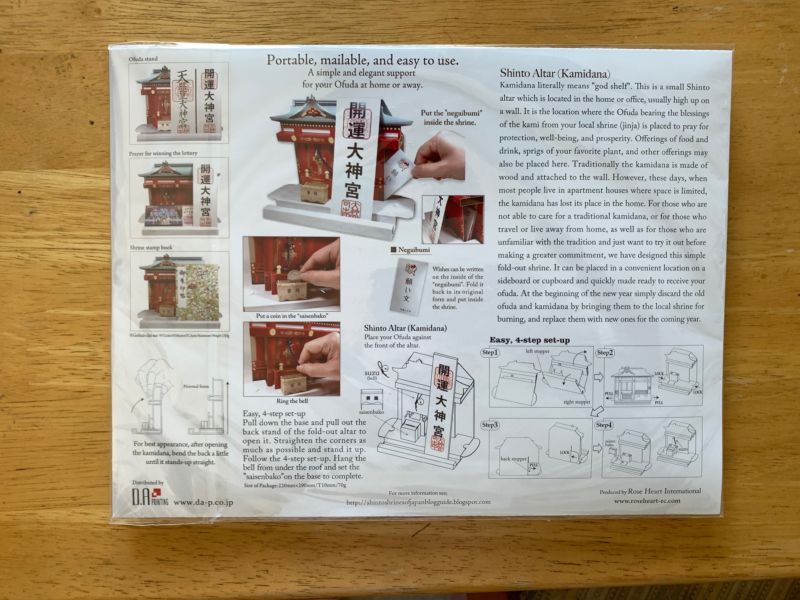

Indeed, their official publications, including books, newsletters, and fliers, do not mention the term “power spot.” That said, hints of implicit approval occasionally emerge. In 2015 I purchased a playful stamp foldout at Chūsha that centered on the “three great power spots of northern Shinano.” Alongside Togakushi, it featured the neighboring Iizuna Shrine and the temple of Zenkōji in Nagano City, a nod to their historical connections and sign of continued coordination. Echoing the sentiment of the priests with whom I spoke, the cartoon imagery represents the power of the three sites through their respective deities. In addition to this souvenir, subtle endorsements sometimes appear on the shrines’ official website under its “news” headlines. In the summer of 2017, these included one hyperlink connecting to a guidebook to Japan’s power spots and another to a popular blog on power spots, both of which featured Togakushi.

Reactions from the clerical community at Togakushi were largely consistent with my findings at other shrines. A middle-aged female shrine attendant at Takachiho Jinja noted that the shrine neither promotes nor rejects its reputation as a power spot. In a separate conversation, one of its younger priests elaborated on this stance with his own take: the shrine lends itself to multiple interpretations, power spots included. As such, he welcomes power spot seekers and does not find the concept to be necessarily wrong or misguided. That said, he prefers a more expansive definition for the site—one that does not cling too narrowly to a specific set of terms and discourse.

I received a similar response from a priest of nearby Heitate Jingū, a village shrine located in central Kyushu that has received national attention in recent years as a power spot. When I asked him if the shrine was a power spot, he replied with a twinkle in his eye that he doesn’t know (Wakaranai…) —a response that leaves the door open for flexibility on the issue. He then offered his own interpretation: those who come to his shrine to “receive power” (pawā o itadaku) should later reciprocate by engaging in work that will benefit others.

The most unease I encountered—excepting Ise—came from a young male priest at Aso Jinja, located in the Aso Caldera of central Kyushu. He too did not oppose the idea of power spots and felt grateful for the increased number of visitors it brought. That said, he expressed some annoyance with those who rushed in and out of the shrine, consumed primarily by its status as a power spot and uninterested in further engaging with it.

While his feelings are probably shared by others in the Shinto clergy, the general impression I received was twofold: one, the reputation as a power spot contributes to the overall economic well-being of communities otherwise facing long-term downward trends; and two, the idea of the power spot is viewed as compatible with long-standing notions about the power of the kami. These responses represent local economic and religious concerns that, for the most part, Jinja Honchō has not given significant weight.

********************

For more on power spots by Caleb Carter, explaining the development of power spots in Japan, click here. For a previous posting on Togakushi, see here.