The Saio-dai arrives at Kamigamo Jinja with her retinue

One of Kyoto’s Big Three Festivals is reaching its highpoint on Wednesday (May 15). The Aoi Festival, sponsored by the World Heritage shrines of Shimogamo and Kamigamo, is the city’s oldest. According to the ancient record Nihon Shoki, the festival dates from the sixth century. Like the Gion Festival, there are a series of purification rites that take place prior to the big parade that is the centrepiece of the festival, when some 500 people take part in a procession dressed in historial garb, pinned to which is an aoi leaf (type of hollyhock). Over the next couple of days, Green Shinto will be featuring highpoints of the festival.

Today concerns the Saio-dai, a young lady who represents the imperial princess who in ancient times was attached to the shrine as titular head (Saio – the ‘dai’ of Saio-dai means representative). Because she is a symbol of purity, she should be young, unmarried and of a good family background with good manners. The girls are usually selected from families of ancient vintage with high esteem such as a background in traditional arts and crafts. This year, as can be seen below, she’s from an incense making family. Notice too that she has a most respectable and appropriate hobby – the tea ceremony.

The Saio-dai wears the most beautiful clothing and captures all the attention, with a throng of photographers clustered around her. During the rituals and the procession, she has to dress in the twelve-layered kimono (junihitoe) that was worn to the most formal ceremonies of the Heian court. The choice of the dazzling colours for the twelve layers was considered a fine art, and the result is usually a visual delight. The total weight of the costume comes to something like half the weight of the young female, and if the weather is anything like today (sunny and 27 degrees) it will be close to torture as the Saio-dai is paraded through the streets.

Congratulations and good luck to this year’s beauty queen!!

***************

Rika Ouno Selected as Aoi Festival’s 64th Saio-dai

Kyoto Shimbun 8 May 2019

Rika Ouno who has been selected as the 64th Saio-dai (dressed in ordinary kimono at a hotel in Kamigyo Ward, Kyoto)

Rika Ouno, a 23-year-old company employee living in Sakyo Ward, Kyoto, has been selected as the 64th “Saio-dai,” heroine of the Aoi Festival, which will be held on May 15. The festival is known as one of the three major festivals of Kyoto. This announcement was made by the preservation society of the Aoi Festival Procession, located in Kamigyo Ward, on April 15.

Rika Ouno is the second daughter of Kazuo Ouno, who manages “Ouno Kungyokudo,” a maker and seller of incense in Shimogyo Ward, Kyoto. She graduated from Doshisha University last September. This spring she began working for Murata Manufacturing Co., Ltd. While she was at Doshisha High School, she served as a captain of the lacrosse team. Her team won the national championship, and she was named the most valuable player. She began learning German during her high school days, and studied in Germany for a year during university. Her hobby is tea ceremony.

During a press conference held at a hotel in Kamigyo Ward, Ouno shared her recollections. “I was an elementary school student when I saw the Aoi Festival and was touched by the beauty of the women’s procession.” As she will be Saio-dai in the first Aoi Festival in Reiwa, or the symbolic reign of the new emperor, she said, “The Aoi Festival is the festival to pray for the peace and security of our country. I would like to play my role praying that the next reign is also peaceful. I will take care of my health to fulfill this duty.”

The role of Saio-dai was restored in 1956, taken from the tradition of “Saio,” or imperial princesses who served Kamigamo Shrine and Shimogamo Shrine in the Heian Period. The system of selecting a female commoner to replace the Saio has now become established, and the Saio-dai [Saio-replacement] has become an integral part of the Aoi Festival.

**************

For a report on the 2014 Saio-dai, click here. For an interview with a Saio-dai, see this original piece.

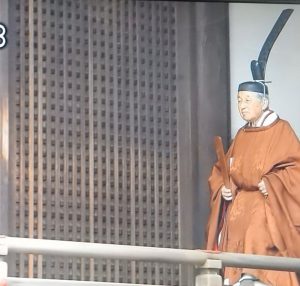

Dressed in the most formal of kimono, the Saio-dai has to perform ritual ablutions and offerings in advance of the main procession

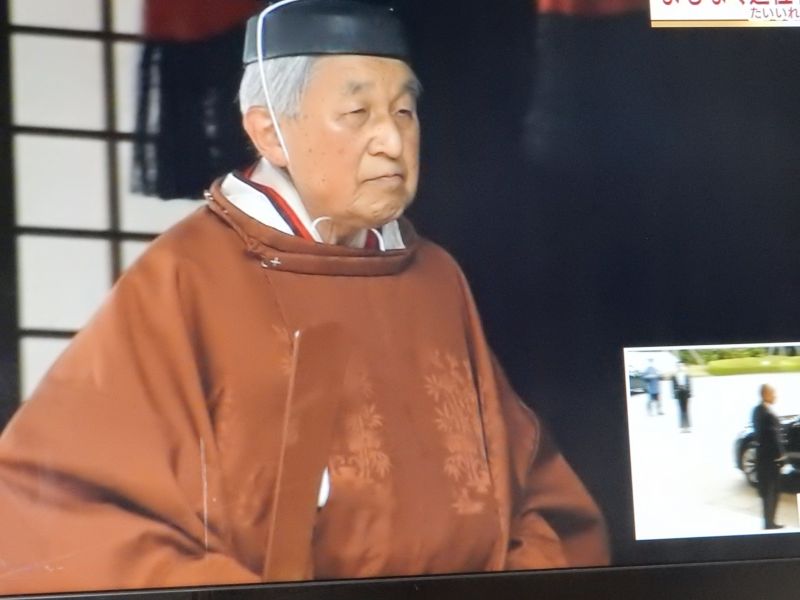

This morning we enter a new historical period called Reiwa as Emperor Naruhito begins his reign. It’s a very different feel from the beginning of the Heisei Era in 1989, as there is no death preceding the ascension of the new emperor – for the first time in 200 years. The sense of change is enhanced by the attendance at this morning’s ritual by a woman. Though female members of the imperial family are not allowed to participate, those in attendance included a female member of the cabinet. – an historical first (see below). Just over five minutes for the whole ceremony, and not a single word spoken! Would that every Japanese ceremony were like that…

This morning we enter a new historical period called Reiwa as Emperor Naruhito begins his reign. It’s a very different feel from the beginning of the Heisei Era in 1989, as there is no death preceding the ascension of the new emperor – for the first time in 200 years. The sense of change is enhanced by the attendance at this morning’s ritual by a woman. Though female members of the imperial family are not allowed to participate, those in attendance included a female member of the cabinet. – an historical first (see below). Just over five minutes for the whole ceremony, and not a single word spoken! Would that every Japanese ceremony were like that…