Before heading for the interview with Sakai-gami, respected yuta of northern Oshima, I went in search of the mythical origins of the island culture. According to brochures, there’s a hill with a monument celebrating the myth of Amanchi and the first arrival of ancestors to the island. It’s a common story amongst ancient cultures living close to the seaboard, and in Okinawa the awe-inspiring Seifa Utaki marks the site of a similar myth of arrival from a paradise across the seas.

Finding the way to the monument was not easy, and local villagers appeared to know nothing about it. Eventually we found someone who did know, and rather oddly the way led up a curving road with signs saying it was for the exclusive use of the Self-Defense Force. However, round one of the corners was a small wooden sign pointing into the undergrowth where a narrow trail led towards the monument. The myth tells of a male and female god descending onto this Oshima Hill – somewhat similar to Izanagi and Izanami descending onto Awaji Island.

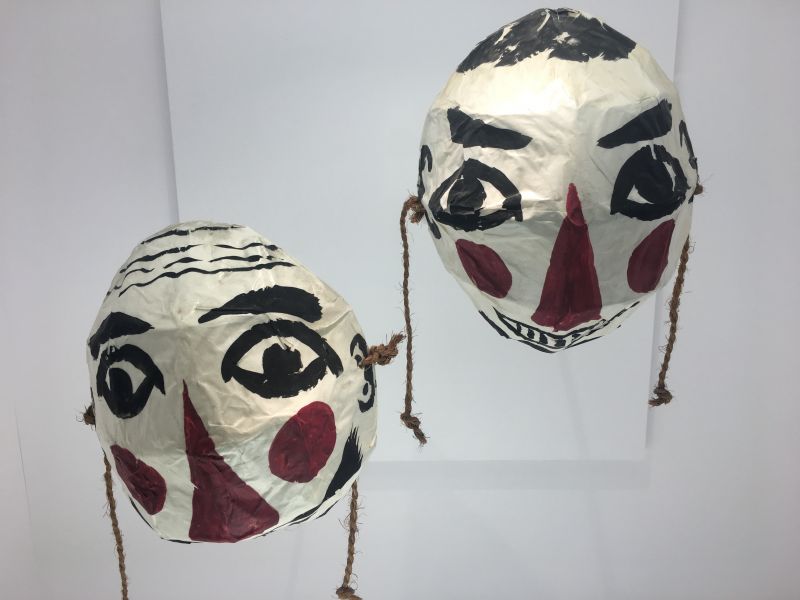

View from out to sea, from where the mythic original ancestors came

The Amanchi myth monument marking where the original kami settlers descended

Before heaading to Sani village where Sakai-gami lives, we dropped in at a store you can buy a handy set of salt and shochu (360 mm bottle), which make up the obligatory offering, together with a monetary ‘donation’ depending on one’s feelings. When I pressed my informant as to the going rate, I got an answer of around ¥3500 for locals and ¥5000 for outsiders.

The village of Sani where Sakai-gami lives has a forbidding atmosphere, with low-lying dilapidated houses, narrow lanes and high walls, seemingly barricaded against the outside world. As it stands on the coast, it needs to safeguard itself from the elements and the force of typhoons. But the settlement has clearly passed its sell-by date, rusty, overgrown and aging like its population.

We stopped to ask where the village shrine was, but the villager we asked claimed he’d never heard of one. Eventually we found it at the end of a lane leading past the white elephant of a brand new primary school which no doubt involved tax-payers money being diverted into someone’s pockets. By contrast the Itsukushima Shrine was old and neglected, the wash basin bereft of water and the Haiden strewn with abandoned objects.

We were easily able to locate Sakai-gami’s house, however, for not only did everyone know where it was, it was also the only house with an extra third storey, a sign of prosperity. Nonetheless access to the inside was far from clear, and the waiting room a picture of colourful confusion. Origami, vases, ornaments, lucky charms, family pictures, a hanging scroll of carp climbing a waterfall, names of grandsons in calligraphy, a picture of the emperor and empress, magazines, cuttings – this was a waiting room to capture your attention!

Squeezed amongst the paraphernalia was a bare kamidana, with two sakaki branches, offerings of incense and water. No ofuda, or altar. It was very dusty, I noticed, and with little regard for the cleanliness that characterises mainland Shinto. It reminded me of the cavalier attitude to sacred sites in Okinawa, which are strewn with litter and leftovers from picnics.

Entrance to Sakai-gami’s house – but which sliding door to open?

The unsigned way round to the waiting room entrance

The colourful waiting room, which doubles as the family living room. Through the thin sliding door you can clearly hear the previous person’s consultation.

The kamidana is plain, with no expense on ofuda or altar pieces for the invisible kami

Much of the room was a feast for the eyes, but whatever would Marie Kondo think?

It turned out that Sakai-gami had double booked me with a mother and daughter who had come all the way from Naze City some 45 minutes away. We got chatting and the mother told me she usually consulted a yuta closer to her house, but she was indisposed. Sakai-gami had a reputation, so she had come here for a physical problem with her digestion, while her daughter had a personal problem.

There was a magazine on the table with an article featuring Sakai-gami which gave some background information. She was the seventh of her family line to follow the kami path (shamanism is often hereditary). She’d married young and after the early death of her husband, the kami had entered into her at the age of 31 (a pathway similar to the sickness and involuntary possession typical of Siberian shamans).

The tokonoma was a riot of colour and ornaments

During the consultation with mother and daughter, which lasted some 40 minutes, Sakai-gami took a telephone call which I could clearly hear. It was from the head of a small family business, who rang to say one of the employees had handed in his resignation. The caller wanted to know if he should let the employee go or not. ‘Why not,’ said Sakai-gami, ‘You can always find a new employee. Perhaps a better one.’

When it came my turn to enter the consultation room, I found a lively little woman, full of confidence, who after taking my date of birth and establishing I was born in the year of the Ox launched into a lengthy ramble about my character that didn’t stop for some twenty or thirty minutes.In fact her apparent ability to talk nonstop throughout the day was the most impressive quality.

It was all very hit and miss, with generalities about preferring job satisfaction to making money and a liking for travel and adventure (your average home-lover is hardly likely to end up on the northern peninsula of Amami Oshima!). There were suppositions that were wide of the mark, and at no point did she even suggest that she might be talking with divine inspiration.The only difference from a typical fortune-teller was that she took my bottle of shochu and poured half of it into a glass to be set with the incense and candles before her makeshift altar.

After about half an hour, she asked me if I had any worries, so I told her I was wondering about whether to grow old in England or in Japan. ‘In Japan of course,’ she declared without hesitation. ‘It’s easy to live here, the people are kind, there’s no danger like in foreign countries where people have big egos and shoot guns.’ There was something about the patriotic sentiment in this tiny corner of a remote island that made me smile.

The day before, she told me, a Brazilian and a Russian had come to consult her, and on busy days she has up to 20 people. Despite my disappointment at the lack of any semblance of shamanic inspiration, she must have some special quality to have built up such a reputation. She has clients every single day of the week, and the only break for a holiday, she told me, is at Oshogatsu. I couldn’t help thinking of that third floor that marked out her building.

In Korea shamans do everyday business as fortune-tellers, and I suspect Sakai-gami’s business is similar. Her popularity suggests a lingering attachment to the old pre-Satsuma style of religion, and next time I go to Amami (as I surely will) I will try consulting with a different yuta by way of comparison and to attend one of the six major ceremonies that are apparently still carried out by the noro priestesses.

Sakai-gami in her consultation room. She sits on a small stool, with clients on the floor beside her. Incense, candles, dried rice, fruit, shochu and a round mirror decorate her altar, dedicated to Amaterasu Okami.

The Amami islands lie between Kyushu and Okinawa. Though technically they belong to Kagoshima Prefecture, they have more of the feel of Okinawa. There are five inhabited islands in the archipelago, of which Amami Oshima is the biggest. Total population is around 70,000.

The Amami islands lie between Kyushu and Okinawa. Though technically they belong to Kagoshima Prefecture, they have more of the feel of Okinawa. There are five inhabited islands in the archipelago, of which Amami Oshima is the biggest. Total population is around 70,000.