Green Shinto members will be aware that as a supporter of animal rights we are appalled at some of the treatment of animals in Japan, and in particular at places related to Shinto festivals. Far from speaking out against animal cruelty, as one might expect from a ’nature based religion’, Shinto has rather shown itself indifferent at best and a supporter of such nationalistic policies as whale-hunting.

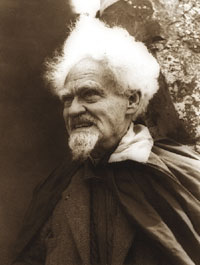

One of the bears formerly at the Ainu Museum in Hokkaido (courtesy Jann Williams)

Previously on Green Shinto we have featured the disgraceful and inhumane conditions of the bears at the Ainu Cultural Museum in Hokkaido. Ainu are known for worshipping a bear deity, but that doesn’t mean they have any sympathy with individual bears. Far from it in fact.

From a young age the bears were kept in small cages of concrete with no access to the outside world. Worse than someone on death row, in fact. They had never seen grass, never tasted freedom, and never eaten anything but rice. Several Green Shinto readers remarked on the cruelty of the conditions, including Australian Jann Williams who supplied photos. We hoped to raise awareness of their plight, and the animal rights group to which we are attached (JAWS) also worked on the case.

Now I’m delighted to report great news!!! The bears have been liberated and transported to comfort in an award winning Yorkshire wildlife park where they will be able to enjoy the new year to their hearts’ content. Amazingly on their new diet they have already put on six stone. Their wishes – and ours – have finally come true.

“”””””””””””””

Report here from The BBC… It’s worth watching the video .https://www.bbc.co.uk/…and-south-yorkshire-45081527

Four endangered bears have been re-homed in Yorkshire after being transported more than 5,400 miles from Japan.

Riku, Kai, Hanako and Amu had been living in cramped conditions at a museum on the island of Hokkaido.

All four are now settling in to their new home at the Yorkshire Wildlife Park (YWP), near Doncaster, after being flown from Tokyo to London.

Animal charity Wild Welfare said the bears will receive “rehabilitation, enrichment and lifelong care”.

The Ussuri brown bears, two aged 17 and two aged 27, were brought to the UK from a museum in Japan.

YWP animal manager Debbie Porter said the loading had gone “like clockwork”.

The bears were being kept at the Ainu Cultural Museum when they came to the attention of Wild Welfare.

Georgina Groves, projects director at the charity, said “The living conditions these bears have faced for much of their lives are sadly reflective of the conditions that many captive bears in Japan are in.

“We really hope these four beautiful bears can raise the profile for others and help us work with zoo and welfare organisations to secure a better long-term future for them all.”

The Ussuri brown bear, also known as the black grizzly, can weigh up to 86 stone (550kg) and live up to 35 years.

The taste of freedom and a happy new year for the Ainu bears

“”””””””””””

For previous reports on this issue, see here.

Following on from the series investigating the links of Shinto and Zen, this piece from Wikipedia struck me as insightful about the architectural and aesthetic overlap between the two practices. It concerns the Katsura Imperial Villa (or Detached Palace) in the west of Kyoto, which many consider to be the sublime example of a traditional estate. Shinto values of simplicity, naturalness and harmony with nature are mixed with the desire for contemplation and transcendence of the ego (For the full Wikipedia description see

Following on from the series investigating the links of Shinto and Zen, this piece from Wikipedia struck me as insightful about the architectural and aesthetic overlap between the two practices. It concerns the Katsura Imperial Villa (or Detached Palace) in the west of Kyoto, which many consider to be the sublime example of a traditional estate. Shinto values of simplicity, naturalness and harmony with nature are mixed with the desire for contemplation and transcendence of the ego (For the full Wikipedia description see