Yesterday I had lunch with Danish Shinto expert Esben Andreasan. He kindly gave me his book on “Japansk Religion” which contains s a compilation of 18 significant texts on Shinto divided into sections on Mythology, Ritual, Nationalism and Modernity. Some of the pieces look intriguing and I’d dearly love to read them. Trouble is I can’t read Danish!

Yesterday I had lunch with Danish Shinto expert Esben Andreasan. He kindly gave me his book on “Japansk Religion” which contains s a compilation of 18 significant texts on Shinto divided into sections on Mythology, Ritual, Nationalism and Modernity. Some of the pieces look intriguing and I’d dearly love to read them. Trouble is I can’t read Danish!

One of the topics that came up during our discussions was the matter of rural depopulation and the problems facing Shinto in the near future. Both Shinto and Buddhism are facing a crisis as society ages and young people migrate to the cities. Shrines and temples are beginning to find it increasingly difficult to survive along traditional lines. Indeed, many rural practices are being abandoned for good.

In her Japan Times column this month Green Shinto friend Amy Chavez gives a great example of what is happening by drawing on her own experience on the Inland Sea island of Shiraishi. (The following is an extract; for the original article please see this link.)

*************

The death of a Japanese countryside festival

by Amy Chavez, Japan Times Oct 31, 2018

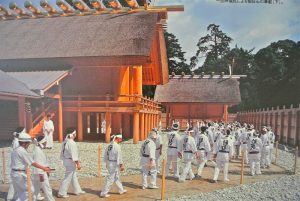

The residents, 60 percent of them over 60 years old, are garbed in festival gear: strips of cotton hachimaki cloth tied around their heads, colorful happi coats belted around their waists and their black tabi shoes gripping the pavement. They’re pulling a large wooden mikoshi festival float down the narrow street past rows of houses, just as their ancestors did over 300 years ago.

This is my neighborhood, on an island of just under 500 people in the Seto Inland Sea. I’m pulling this mikoshi too. We’re celebrating the autumn festival, which used to ring in the seasonal harvest, but which now serves as the one day of the year when people let their guards down, let bygones be bygones and just have fun together. The sake is brought out and the locals dance in the street. Some have grown-up children who return with grandkids to take part in the annual festival. But most do not come.

Nowadays non-traditional vehicles are used

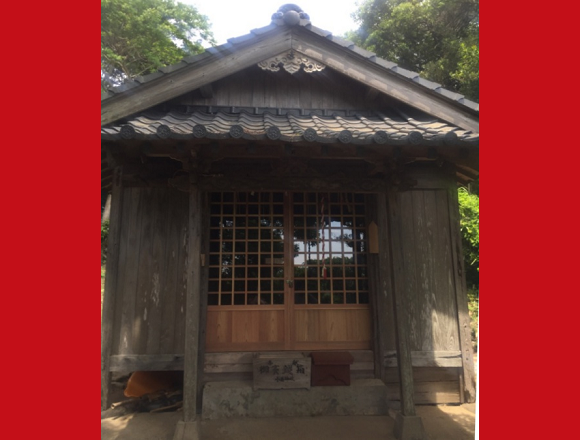

We’re tugging the float, a wooden mikoshi on wheels, along the street to the main Shinto shrine. We pull it past houses, some of which are occupied, some not. Of those unoccupied, some are collapsing, some not.

Though the residences have changed in appearance, losing their luster over the years, the mikoshi still retains its dignity, albeit with a few adjustments. The heavy structure of Japanese cedar used to be carried on mens’ shoulders, but years ago it was given wheels to make up for the declining pool of strong young people who had moved to the cities to take office jobs.

Each neighborhood (previously eight but now reduced to five) pulls its own mikoshi through the streets and up to the main Shinto shrine, where the island’s guardian deities reside. There, more sake drinking and dancing takes place. Then, finally, we treat the gods to a symbolic tour of sacred spots around the island.

The junior high school students have their own dedicated mikoshi that they still carry on their shoulders. Although it used to be only the boys who shouldered it, now all the students do: five boys and three girls.

The lion and maiden dances performed in honor of the gods at the main shrine by appropriately costumed elementary school children were discontinued three years ago. Next year, the elementary school will close due to a complete absence of students.

As the years draw on, the residents do too, and the neighborhoods shrink further, so they must find more ways to compensate for the diminishing manpower. One has scaled down its mikoshi to the size of a baby buggy, while another sits the structure on the back of a pick-up truck, leaving the residents to saunter along behind it.

Carrying mikoshi up steep flights of stairs requires enormous strength

As for my neighborhood, this year we abandoned our mikoshi halfway through the day. After the visit to the main shrine, we dropped it off at its home parking spot, then piled into the back of a pick-up truck to finish the route. It wasn’t the pulling of the wheeled shrine that was proving difficult, it was the kilometers of walking required to accompany it to the different sacred sites scattered around the island. The younger individuals had no problem, but no one wanted to leave the elderly behind, so the ad hoc decision was made to park the mikoshi.

This, however, did not go down well with the local policeman, who, after the festival, reprimanded us for violating traffic regulations — namely, riding in the back of a pick-up truck and drinking and driving. On this festival day, most policemen would have looked the other way, but this guy was new. And the law, after all, is the law. People began to feel ashamed of our infraction, even though they thought the policeman silly.

When 300-year-old traditions clash with modern governance, traditions become even more of a challenge to maintain. And the policeman’s admonition only reinforced that times aren’t as good as they used to be.

People are starting to wonder why we’re trying to continue these traditions. It used to be done for posterity, back when posterity was taken for granted. And how would we pull the mikoshi next year?

Back when houses stood pristine, well-maintained and proud, those who couldn’t participate would stand outside their homes along the road leaning on their canes, or waving from their wheelchairs as each precinct paraded past with their festival float. But they no longer do this. Perhaps it’s because there’s no one to stand alongside.

Or maybe it’s because if they did wave, they know they’d be waving farewell to a 300-year-old festival.

Amy Chavez is author of “Amy’s Guide to Best Behavior in Japan: Do it Right and Be Polite!” (Stone Bridge Press). Japan Lite usually appears in print on the last Monday Community page of the month.

Carrying mikoshi was traditinally a man’s job but these days women help out

Village children dance as miko, but how long will the supply of children last? The elementary school on Shiraishi is closing…

Amy and islanders in full festival mode

Children’s mikoshi with a home-made touch

Phoenix atop the children’s mikoshi

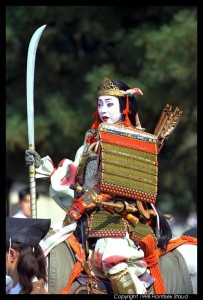

One of the most appealing aspects of the festival is the authenticity of the costumes, which were made of material as close to the original as possible. Even the weaving and dyeing was done in the manner of the age they represent.

One of the most appealing aspects of the festival is the authenticity of the costumes, which were made of material as close to the original as possible. Even the weaving and dyeing was done in the manner of the age they represent.