Green Shinto follower Jann Williams, who is researching about the use of the five elements in Japan, has kindly allowed us to use her latest posting from her website, elementaljapan. We are grateful to her for the following insight into the particular type of shamanistic Shugendo practised on one of Japan’s most famous sacred mountains.

Mt Ontake is a sacred mountain 100 km northeast of Nagoya on the border of Nagano and Gifu Prefectures. At 3067 m it is the second highest volcano in Japan, after Mt Fuji. Pilgrimages to worship Mt Ontake and seek spiritual enlightenment have been made for centuries and continue today.

On 23-24 January 2018 I joined a winter pilgrimage on Ontakesan with the Wani-ontakesan community, led by three Shugendo masters. Undertaking ascetic practices on the mountain in extreme conditions reinforced that we are part of nature and the universe. Sharing this experience with others and hearing the word of Gods and ancestors through a medium – a hallmark of Mt Ontake worship – was profound and empowering.

The rituals and prayers associated with the pilgrimage were a sign of deep respect and reverence for Mt Ontake and its Gods, and the ancestors memorialised on its volcanic slopes. This transformative experience deepened my understanding and appreciation of the elements in Japan and Japanese culture. It is a pleasure to share my impressions of the two days spent with this remarkable community of faith.

Mt Ontake viewed from Mt Hakobuto. Unlike Mt Fuji the volcano is currently active, most recently erupting without warning in 2014. Many lives were lost and the mountain top is now out of bounds to pilgrims and hikers. The eruption is a reminder of the elemental forces that continue to actively shape Japan. Source: Wikipedia Commons

Shugendo has been practiced on Mt Ontake for centuries. It is a highly syncretic and ancient religion found only in Japan. Shugendo practices and teachings draw on Shinto, Esoteric Buddhism, Taoism and shamanism, and the rituals incorporate both godai (the five Buddhist elements) and gogyo (the five Chinese elements). Nature and the elements are a fundamental part of the religion and way of life of the practitioners who seek spiritual power and enlightenment through ascetic training in the mountains. My first experience with a major Shugendo ceremony was at Kinpusenji in Yoshino in July 2016. It made a deep impression that is recorded in the post Fire up, Water down. Going from an observer of a ceremony there, to participating in a pilgrimage on Mt Ontake, took my understanding and appreciation of Shugendo to another level.

Until the late 1700s, Mt Ontake was the exclusive reserve of Shugendo ascetics who undertook severe austerities before their annual pilgrimage. Around this time two ascetics – Kakumei and Fukan – opened pilgrimage paths on Mt Ontake. These are referred to as the Kurosawa and Otaki routes, respectively. By opening access for lay people to Ontakesan the nature of worship changed, leading to the formation of numerous and widespread pilgrim groups (kou). Fukan was a great Shugendo master and has special significance for Wani-ontakesan. The Mt Ontake faith they practice differs from Ontakekyo, a Shinto sect with which other pilgrim groups are associated.

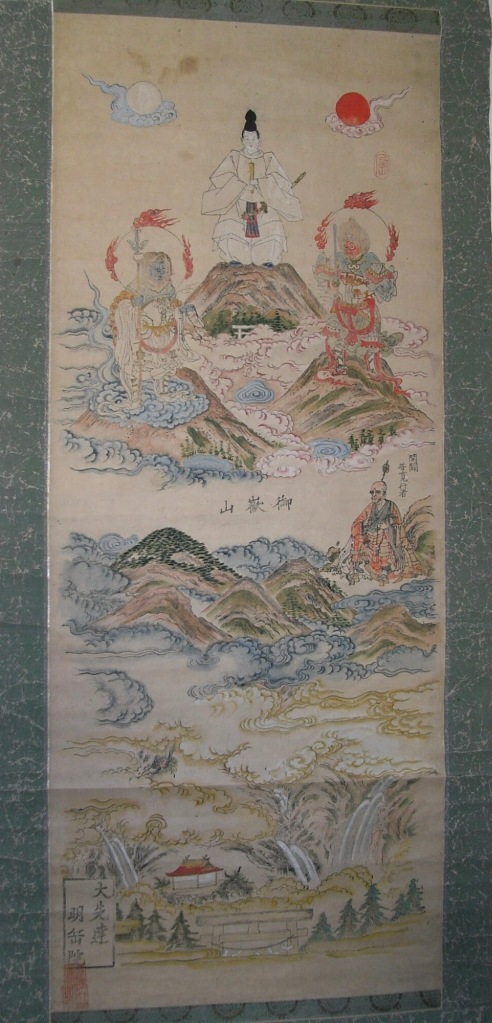

A kakejiku (hanging scroll) of Mt Ontake. Source: Doukan Okamoto

In the popular kakejiku shown above, Mt Ontake comes alive as a place of worship and home to the Gods. At the top of the scroll Kunitokodatai-no-mikoto, Oonamuchi-no-mikoto and Sukunahikona-no-mikoto are represented – these Gods are enshrined at the base of the mountain. The three main Gods of the mountain are depicted in the middle section with Ontakesan-zaou-daigongen in the centre, Hakkaisan-daidura-jinnou on the right and Mikasayama-touri-tengu on the left. Kakumei and Fukan are shown at the bottom right and left, respectively, either side of Fudo Myoo (‘the Immovable Wisdom King’). On the kakejiku, the latter three figures are shown located around a sacred waterfall, of which there are several on Mt Ontake.

Yasunari (centre), Motoshige (left) and Doukan Okamoto – the Shugendo masters that led the winter pilgrimage. ( Source: Doukan Okamoto)

Wani-ontakesan made a pilgrimage to Mt Ontake twice a year, in both winter and summer. Winter is considered the more challenging because of the snow and extreme low temperatures. The Okamoto family has been leading the mountain pilgrimages for over 100 years. The head of the family and Wani-ontakesan community, Yasunari Okamoto is shown in the middle of the above image with his sons, Motoshige and Doukan. The brothers are twins and share a strong bond. The symbol on the hachimake (headband) worn by these masters represents Mt Ontake and was designed by Fukan. Motoshige and Doukan are wearing the distinctive clothing of the Shugenja, those who obtain spiritual powers through hardship on the mountains. Each item of clothing is symbolic and has deep meaning. The mudras – energising, symbolic hand gestures – performed by Yusanari, Motoshige and Doukan are an essential and focal element of Shugendo rituals.

Reijinhi (Stone memorials), Mt Ontake. January 2018.

One of the striking features of Mt Ontake found nowhere else in Japan is the stone monuments known as reijinhi. It is estimated that there are over 20,000 of these memorials on Ontakesan. They are the spirit abode of reijin, the title given to ascetic practitioners and devotees of Mt Ontake after they have died. Reijin are an important part of the Wani-ontakesan faith, as they are to other pilgrim groups who visit the mountain. The monument sites have an overwhelming spiritual and mystical ambience during winter. The grey of the reijinhi and deciduous trees, in combination with the white of the snow, directly connects one to nature and is a powerful reminder of the depth and significance of worship at the mountain.

Takigyo, Mt Ontake. January 2017. (Source: Kei Shima).

Both takigyo (waterfall practice) and kangyo (practice in winter) are part of the winter pilgrimage on Mt Ontake. Takigyo is one of the best known ascetic practices associated with Shugendo. It is a form of meditation designed to cleanse the body and mind – one that is not commonly performed in the extremes of winter. Splashing water on your body before standing under the sacred falls, and reciting the Fudo Myoo mantra (an important deity in Shugendo and Esoteric Buddhism) while in them, are components of takigyo on Ontakesan. Seiji Inagaki, who I shared the 2018 pilgrimage with, is shown in the image above standing under the falls reciting the mantra. Doukan and Motoshige Okamoto are present and have their backs to the photographer. Women undertaking the practice wear a white top and pants under the waterfall. Whilst undertaking takigyo I was oblivious to the cold. The combination of the sacred falls, impact of the cascading water on my head, and chanting of the mantra focused my mind and senses exclusively on the moment.

Kurosawa Hakkaisan Shrine, Mt Ontake. January 2018.

A significant ascetic practice during the pilgrimage involved traversing steep terrain in the fresh snow during the day and night to visit spiritual sites. Our first destination was the Shrine dedicated to Hakkaisan, one of the three main Gods of Ontake. A small group of pilgrims prepared the Shrine in advance (image above) by lighting candles and incense and positioning items on the alter to be blessed by the Gods. The offerings included food, drink (sake, beer) and personal items that were subsequently removed. This practice was repeated elsewhere on the mountain over the course of the pilgrimage. The service at the Shrine included mantras for Hakkaisan Daizura-Sin Nou, Kakumei-Reijin, Ebisu-Ten, Daikoku-ten (Ebisu’s father) and Kobo-Daishi. After the outdoor service was completed we took tea in a nearby hut before moving lower on the mountain.

The spectacular late – afternoon view from Kurosawa Hakkaisan Shrine, Mt Ontake. January 2018.

Shugendo masters Motoshige (left) and Doukan Okamoto, Mt Ontake. January 2018.

Oza, or mediated spirit possession, occurred three times on the pilgrimage beginning on the first evening after the service at Kurosawa Hakkaisan Shrine. Along with reijin, the trances are considered the defining feature of Mt Ontake worship. The first description of the ritual in English was by Percival Lowell in 1895 in his book on occult Japan. A number of academic treatises and popular articles have been published since that time. Probably the best known coverage is in The Catalpa Bow (1975), a comprehensive study by Carmen Blacker of shamanistic practices in Japan. Experiencing the ritual first hand, several times, I find has given me a connection that no written words can provide.

Extensive ascetic training was and continues to be undertaken by Motoshige and Doukan to perform the seminal and demanding Oza roles of nakaza (medium) and maeza (who provides vital support), respectively. Motoshige is transformed during these sessions. On the first night the deities who spoke through him were Hakkaisan, one of the main Gods of Ontakesan, and Evisuten. The words of the Gods were received by all Wani-ontakesan followers. The words were heard by all, providing a strong bond between those present. The advice to me related to the soul of my mother Edna who passed away in late December 2017. My feeling is that the intimate spiritual connection between nazaka and maeza is enhanced because of the close twin brother relationship of Motoshige and Doukan. The intensity and effectiveness of the trance and spirit possession I observed was extraordinary.

Otaki Satomiya Shrine, Mt Ontake. January 2018.

Both the Kurosawa and Otaki pilgrimage routes have a Satomiya Shrine at the base of the mountain that acts as a gateway. The stairs in the above image lead to the Otaki Satomiya Shrine where the Gods Kunitokodatai-no-mikoto, Oonamuchi-no-mikoto and Sukunahikona-no-mikoto are enshrined. The first major service on the second day of the pilgrimage was held at the Shrine, led by Yasunari Okamoto. Recitation of mantras and sutras occurred throughout the pilgrimage including chanting the Hogyo-in-Dharani as we walked. The call and response nature of that chant was invigorating and strengthened our connection to Ontakesan.

A small group of pilgrims walked the higher reaches of Mt Ontake on both days. From the left are Noritoshi Nakata, Takao Takenaka (with the black glove), Keiji Okushima, myself, Motoshige Okamoto and Doukan Okamoto. It was Keiji who introduced me to Wani-ontakesan. The friendship and support he and his wife Kaori have shown me has been immeasurable. Seiji Inagaki, who was also part of the group, took the photo.

Shintaki, Mt Ontake. January 2018.

The two kakejiku (hanging scrolls) illustrated in this post reflect the great importance of the sacred waterfalls on Mt Ontake to worshippers. Although most of the water had turned to ice, Shintaki was still flowing during our visit on the second day of the pilgrimage (image above). While walking through fresh snow was hard going at times, especially up challenging terrain (image below), the embodied energy I could feel from the waterfalls, surrounding snow-clad slopes and forest, and my fellow walkers provided much inspiration and sustenance. The mountains and nature are viewed as teachers in Shugendo. There is much to be commended in this belief.

The imposing snow covered stairs to Omata Sansya, Mt Ontake. January 2018.

Prayers at Omata Sansya, Mt Ontake. January 2018.

The final Shrine visited on the pilgrimage was Omata Sansya. In this important place the three main Gods of Mt Ontake are enshrined (image above). Doukan and Motoshige led the prayers to Ontakesan-zao-daigongen (centre God in image), Hakkaisan-daidura-jinnou (God on right) and Mikasayama-touri-tengu on the left. Doukan stated that these Gods show ourselves (Ontake), water (Hakkaisan) and fire (Mikasayama). He also said that Ontakesan-zao-daigongen can change appearance to Fudo Myoo or Marishiten at certain times. My hope is to learn more about these deities and their significance. A number of offerings were presented to the Gods before the service and collected afterwards. These included sacred branches protected in the plastic bags (shown in the above image and illustrated below), that were blessed at each sacred site we visited on the mountain.

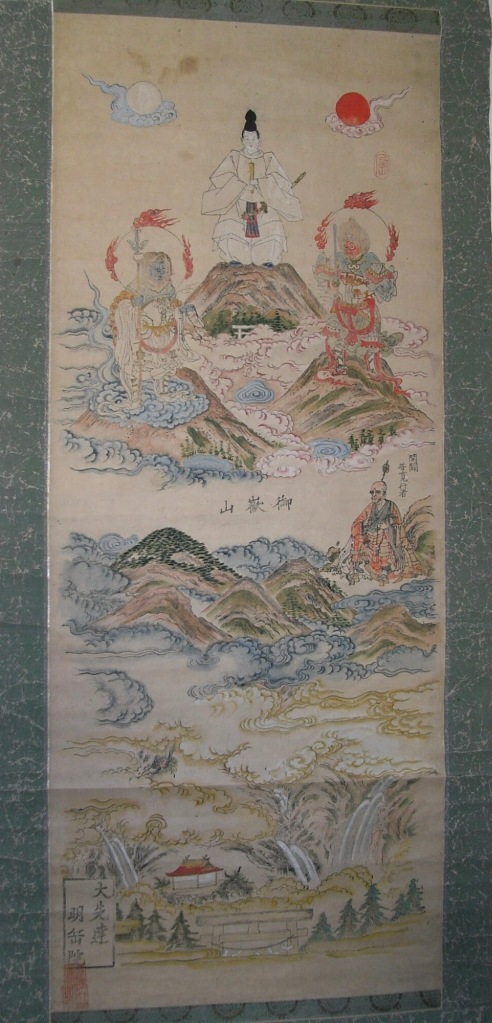

Ancient kakejiku showing the three main Gods of Mt Ontake and Fukan. Source: Doukan Okamoto

The three main Gods of Mt Ontake are splendidly illustrated in colour across the top of the ancient kakejiku shown above. Fukan is located below them to the right of the scroll. The hanging scroll was painted by his disciple Kouzan. The prominence of the sacred waterfalls in the image is striking. The scrolls act as a window to Mt Ontake, as does the Ofuda shown below. The kakejiku and Ofuda evoke images for pilgrims of their experiences and path to spiritual enlightenment at Mt Ontake.

The Ofuda (left) and Osagiri from my winter pilgrimage on Mt Ontake.

At the end of the pilgrimage I was given one of the sacred branches blessed at each Shrine we visited on Mt Ontake (image above). The branch is called Osagiri or Tessen in Japanese. It is dedicated to meals, foods and snacks for the Gods. As described earlier, the Ofuda acts as a window to the spiritual mountain. Both the Ofuda and Osagiri will be an enduring reminder of my pilgrimage on Mt Ontake.

Late night Karaoke on the return to Wani. Winter 2018.

The Wani-ontakesan community has a strong sense of fellowship formed through the deep and shared reverence for Mt Ontake and the family ancestors. On the pilgrimage I felt very welcome and was included in all activities, including karaoke on the return bus trip (image above). It was a first for me and a lot of fun – one of many new experiences that made the pilgrimage such a transformative experience. Yes, even Karaoke can be transformative! It provided a good balance to the deep philosophical and spiritual lessons on the mountain.

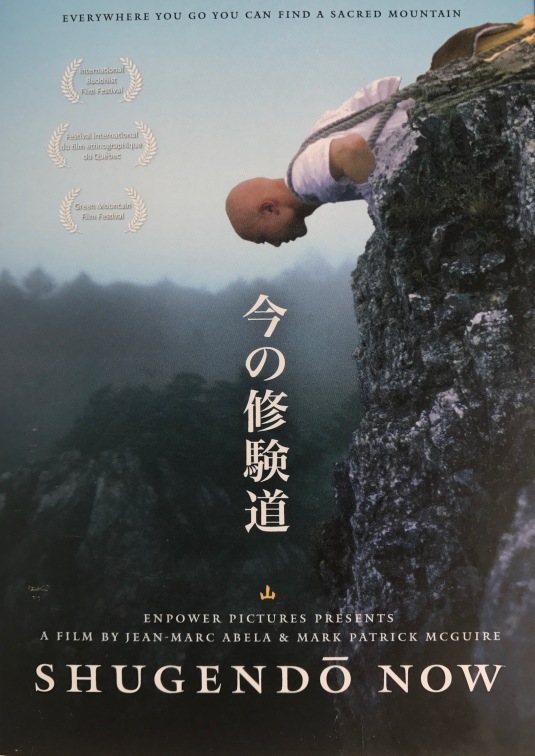

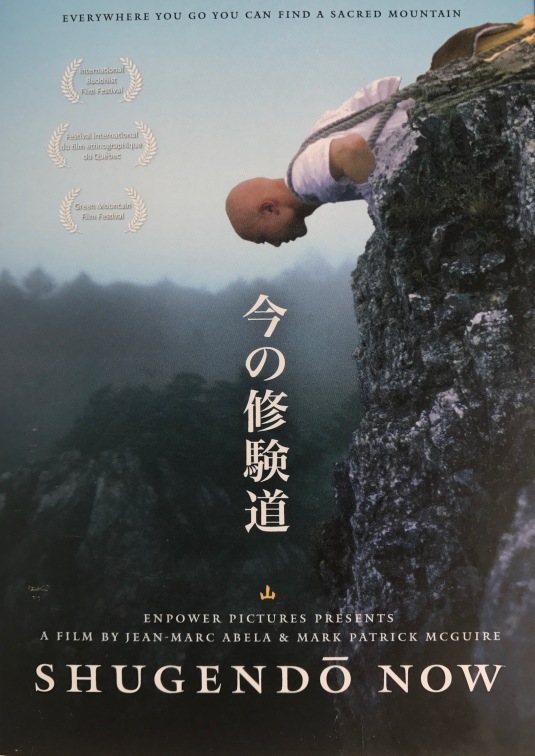

Shugendo Now DVD cover.

The title of this post was inspired by the documentary ‘Shugendo Now‘ released 11 years ago. The documentary tells a compelling story and is recommended viewing. It explores how a group of modern Japanese people integrate the myriad ways mountain learning (through asceticism) interacts with urban life. The focus is on Mt Omine (south of Nara), shown on the cover of the DVD, which along with Dewa Sanzen (west of Sendai) is the location of Shugendo practice apparently best known outside of Japan.

My experience with Wani-ontakesan is a vivid example of how Shugendo is practiced more widely and diversely across Japan than may be appreciated. As well as the twice yearly pilgrimages to Mt Ontake this community of faith undertake ascetic practices on several other mountains including Mt Omine and Mt Fuji. Monthly visits are made to Fushimi-Inari in Kyoto and regular services are held at their place of worship in Wani on Lake Biwa where I have participated in services involving goma (fire) and other Shugendo rituals. For those wanting to discover more, their website and associated blog can be found here (Japanese only). The rituals and practices of Wani-ontakesan are highly syncretic, intimately related to the elements and have a deep history. Shugendo ‘now’ also encompasses the future and the past.

*****************

Click here for a youtube video of just over 5 minutes telling the story of the Ontake faith in visual fashion, particularly the role of Kakumei and Fukan in opening the pilgrim route.

The great hope of Green Shinto, as for many progressive thinkers throughout the Western world, is that we can somehow recapture a proper relationship to nature, based on reverence and communion rather than exploitation. A recent article on the subject by the Brainpickings website articulated this in compelling terms. It is these kinds of sentiments that inspire such affection for Shinto’s animistic roots and its reverence of nature.

The great hope of Green Shinto, as for many progressive thinkers throughout the Western world, is that we can somehow recapture a proper relationship to nature, based on reverence and communion rather than exploitation. A recent article on the subject by the Brainpickings website articulated this in compelling terms. It is these kinds of sentiments that inspire such affection for Shinto’s animistic roots and its reverence of nature. “We cope with [the] awareness of our smallness and finitude by grasping for control and domination of the expansive natural world that lies beyond us. Decades after the theologian Thomas Merton wrote that we suffer from a civilizational sickness leading us to believe that “in order to ‘survive’ we instinctively destroy that on which our survival depends,” Williams writes:

“We cope with [the] awareness of our smallness and finitude by grasping for control and domination of the expansive natural world that lies beyond us. Decades after the theologian Thomas Merton wrote that we suffer from a civilizational sickness leading us to believe that “in order to ‘survive’ we instinctively destroy that on which our survival depends,” Williams writes: