Like hundreds of other limestone-rich mountains in Japan, Mount Buko has given up its mineral resources to fuel the nation’s rapid industrialization in the 20th century. To date, nearly 500 million tons of raw material have been mined from its hills to produce the cement feeding Tokyo’s massive infrastructure needs.

The ongoing excavation that began in the 1920s has left a permanent mark: Mount Buko’s peak, originally at 1,336 meters, now measures 1,304 meters. Its jagged slopes of gray stone terraces have prompted some to call it “Scarface,” in reference to the 1983 cult mob film starring Al Pacino.

But what distinguishes the mountain from myriad others quarried by cement companies is its spiritual significance to the region, known as a treasure trove of folklore thanks to its relative geographical isolation. The Chichibu basin and surrounding highlands is home to over 300 annual festivals, from small rituals in mountain hamlets to the Chichibu Yomatsuri (Night Festival) held each year on Dec. 2 and 3, considered one of Japan’s top three float festivals.

It has also drawn pilgrims for hundreds of years who make their way along an ancient route that links 34 Buddhist temples. At the center of the local folk religion is Mount Buko, a kannabi — a Shinto term meaning realm of the gods.

Shin Sasakubo, environmental activist (photo Alex Martin)

Spiritual activist

For Sasakubo, a dreadlocked 34-year-old classically trained guitarist, photographer and avant-garde artist, an epiphany hit several years ago when he was researching the region’s extinct folk songs.

Since settling back in Chichibu in 2008 after four years in Peru, Sasakubo had been drawn to his cultural roots. While living in Lima, he had frequently traveled to remote Andean mountain villages to learn the indigenous music. His research opened his eyes to his own heritage. “I studied classical music and Andean folk music, yearning for something that wasn’t part of my identity. But I couldn’t help feeling that I will never be truly immersed in cultures I wasn’t born in,” he said.

That led him to dig up Chichibu’s forgotten work songs. Before being overtaken by the cement business, the area had a major silk industry that flourished during the Meiji and Showa eras, spawning numerous folk tunes.While conducting fieldwork, Sasakubo discovered an old rain song that farmers sang during droughts. The practice appeared to have died out in the 1960s as weather forecasts improved. But there was another reason: A chunk of rock near the summit of Mount Buko where the rainmaking rituals took place had been blown apart by miners.

“It was a shock to learn how a traditional place for prayer was destroyed like that,” he said. “I don’t deny industrialization, but it raised many questions.” Sasakubo has since featured Mount Buko in his art, including a short film released in 2015 and a photo collection published in July. His latest and 27th album, which came out in August, includes a solo guitar piece dedicated to Miyamasukashi-yuri, a critically endangered plant in the lily family that grows on Mount Buko.

His efforts to raise awareness, however, have been met mostly with indifference by the local community, which relies on the cement industry as a major source of tax revenue and employment. “The Chichibu we know today cannot exist without Mount Buko,” said Yoshinari Tomita, the mayor of Yokoze, Sasakubo’s hometown, which shares the mountain with the neighboring city of Chichibu.

Tomita described Mount Buko as being multifaceted, serving as an object of worship and symbol of Chichibu while providing the region with a steady flow of income through mining and tourism. “In terms of employment and financial impact, the cement industry is indispensable to Chichibu,” he said. “I understand Mr. Sasakubo’s artistic pursuit, but the issue with Mount Buko is one that cannot be defined as black or white — there are people who make a living from the mountain.”

An image of Mount Buko taken by photographer Buko Shimizu in the 1950s shows the mountain before its slopes were scarred from extensive mining.

Tomita raised the example of the Seibu Chichibu Line, a railway that opened in 1969 to transport cement produced from Mount Buko’s limestone. The route considerably shortened the travel time between Chichibu and Tokyo and still carries many tourists and commuters. “Protecting the environment is important, but we cannot reject the industry. We need to strike a balance,” the mayor said. That sentiment appears to typify how Chichibu has dealt with the issue.

Yutaka Asami, a 35-year-old Yokoze resident who runs a tourism website called Chichiburu, recalls drawing pictures of Mount Buko in elementary school and being taught that the mountain is sacrificing itself for the people of Chichibu. “That was the narrative. It wasn’t about environmental destruction, but about how Mount Buko is being mined for our well-being,” Asami said. Over the years, raising matters related to the mountain has become taboo, he said.

While Mount Buko still contains enough limestone that can be mined for decades to come, sluggish demand for cement poses risks for Chichibu, which remains heavily dependent on the industry. Annual cement production in the nation has nearly halved in the past two decades, according to the Japan Cement Association, from a peak of around 99 million tons in 1996 to 59 million tons in 2016.

When Chichibu Taiheiyo Cement Corp., one of the three cement companies mining Mount Buko, announced a halt in production of the common Portland cement in 2010 due to falling demand, it was met with stiff resistance from the Chichibu Municipal Assembly. In a letter to the company in which the council described Mount Buko as a “mountain of gods,” it urged that production continue, arguing that the area’s development depends on its mining.

Masatsugu Taniguchi, an environmental journalist and former executive director at Taiheiyo Cement Corp., Japan’s largest cement maker and the parent company of Chichibu Taiheiyo Cement, said that Mount Buko represents a unique case. Excavation of the mountain takes place on its northern side, which looks over the city of Chichibu. The south side — which doesn’t contain limestone — is untouched and covered by lush green forests. That meant that unlike quarries that flatten mountains from the summit, Mount Buko retains its silhouette and will continue exposing its brutally scarred surface. “When mountains disappear, people tend to let go and try to forget. But for better or worse, the people of Chichibu will always be reminded of Mount Buko,” he said.

Chichibu appears to be gradually shifting its focus toward sightseeing amid a surge in tourists, taking advantage of its relative proximity to the capital and its rich natural environment. Meanwhile, work is underway by the three cement companies to regenerate some of Mount Buko’s landscape by planting trees, although it’s difficult at this stage to ascertain any visible improvement. Various proposals have been made over the years on Mount Buko’s future, including a plan to turn it into an industrial heritage site. None of the ideas has been set in motion so far.

As for Sasakubo, he spends many days roaming the hills of Mount Buko, taking photographs and searching for artistic inspiration. “The biggest problem is our reliance on the cement industry. That means we’re doomed once we run out of resources — it’s what’s happening in mining towns all over the world,” he said. “We need to send a positive message. We must admit that we’ve been hurting the environment and show that we are reconsidering our actions.”

An aerial photo of Mount Buko taken in 2013 shows its northern slope scarred by decades of limestone mining. | KYODO

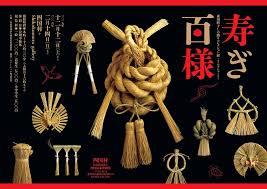

Capturing beauty of straw decorations

Capturing beauty of straw decorations

For the Homeric Greeks, kleos, fame, was made of song. Vibrations in air contained the measure and memory of a person’s life. To listen was therefore to learn what endures.

For the Homeric Greeks, kleos, fame, was made of song. Vibrations in air contained the measure and memory of a person’s life. To listen was therefore to learn what endures.