Arrival

Amidst the throng of humanity at Sapporo station stands a striking sculpture. Busy commuters hurry past, but the lone figure stands defiantly still. Carved out of yellowish wood, it depicts an Ainu hunter in headdress with a long arrow gripped firmly between his teeth. In his hands he holds out a bow in welcome, yet no one pays him any heed. Dignified and rooted, he speaks to another age.

Sapporo in the Ainu language means Vast Dry River (i.e. Plain), a reference to the open land on which it is located. With the influx of migrants from the Honshu mainland, kanji characters were allocated to the name based on the sound and without regard to meaning. In this way, the descriptive Ainu name was written as something akin to Tablet Hood – a tablet on which is written a sad history.

In 1869 the Ainu of Ishikari Plain were pushed aside for construction of a capital fit for a thriving new region. The layout was conceived in grid-like straight lines, and once you step out of the station it becomes apparent, and modernity hits you in the form of a building with thirty-seven storeys. A hundred and fifty years ago there were only a handful of village houses; now Sapporo has a population of nearly two million. Yet despite its size there are wide avenues and open areas, startling for those used to the cramped conditions of Honshu. All that unused space!

******************

Hokkaido Jingu

When I told Hirota san I was going to visit Hokkaido Jingu, the island’s top Shinto shrine, he showed little interest. Shinto is often said to form the foundation of Japanese culture, yet it is not recognised by Hirota’s sect of Buddhism (Jodo Shinshu, True Pure Land Sect). The founder, Shinran Shonin, saw kami as a distraction from the only thing that matters – salvation through Amida’s saving grace.

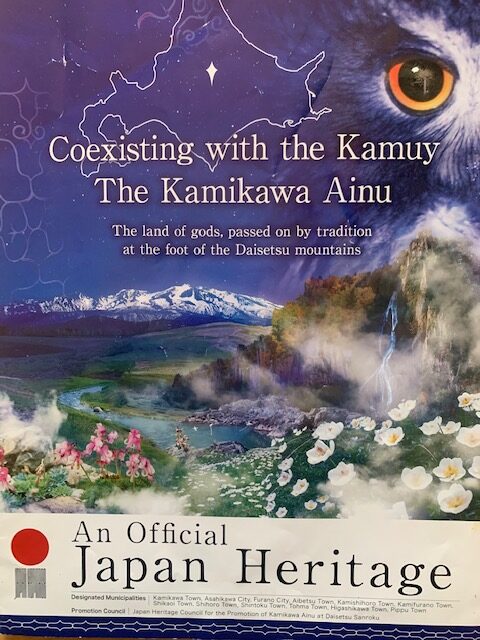

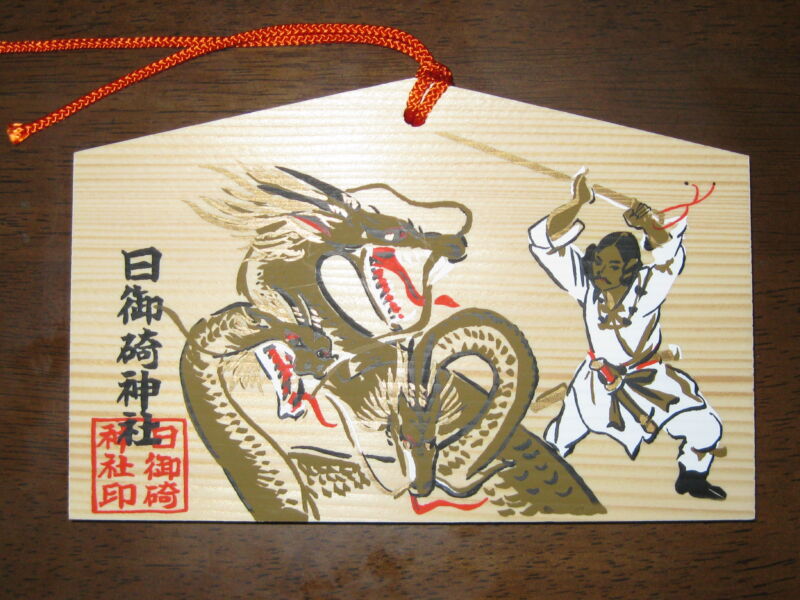

Shinto’s major shrines often boast ancient origins, but those of Hokkaido only date from Meiji times ( a couple in the extreme south claim a seventeenth century foundation, but they are exceptions). For millennia Hokkaido was the domain of Ainu spirits called kamuy, and the decision in 1868 to construct a large Shinto shrine, authorised by the teenage Emperor Meiji, was an assertion of authority. The main kami, Okuni-Tamano-Kami, is translated by the shrine as Divine Spirit of the Land of Hokkaido, indicative of the new order.

The imperial character of the shrine is evident in its stately approach, lined by massive cryptomeria. Unusually, there are wooden cloisters, as if to mimic the grandeur of medieval cathedrals. At the water basin, intended for ritual cleansing, the ladles had been removed to prevent Covid contagion, and the irony was striking – a religion that promotes purity had been disrupted by impurity.

At the Worship Hall were the usual trappings of Shinto, and I wondered if somewhere there might be recognition of the Ainu past. Instead I came upon a Pioneer Sub-shrine , established in 1938 to mark the 70th anniversary of the ‘founding of Hokkaido’. It enshrines thirty-seven pioneers for overcoming difficulties in the development of the island. There was not a single mention of the Ainu, or of the kamuy who for so long had co-existed with them.

These days Shinto is being recast by some as a nature religion concerned with environmental matters, though offcially it remains centred on the emperor as representative of a divine lineage. The spread of Shinto abroad has prompted greater examination of its claims to universality, based on the animist belief in kami-imbued natural phenomena such as rocks and trees. Supporters of this view like to point to the sacred groves with which shrines are surrounded as evidence of Shinto’s green credentials. Hokkaido Jingu is no exception, being set in a large area of mixed woodland. A noticeboard claims it is proof of Shinto’s bond with nature, though with no hint of irony it stands alongside a sign banning pets.

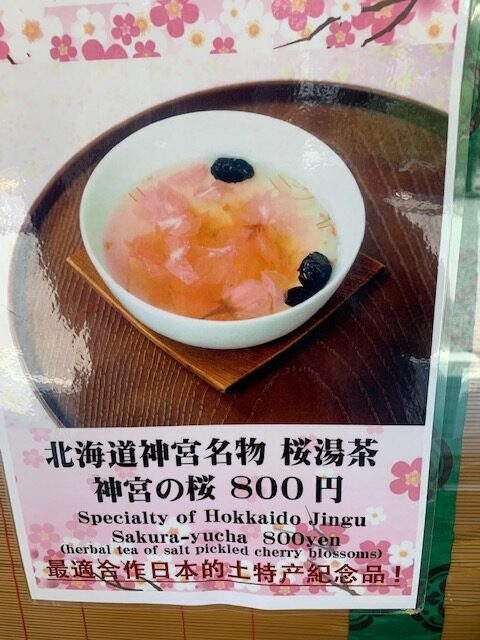

The woods are home to red fox and squirrel, as well as a variety of birds. Though it was early autumn, the shrine was offering ‘Herbal tea with pickled cherry blossom’, and the subtle taste was much in keeping with Japanese traits: understated, refined and delicate. Inevitably, someone had counted the cherry trees (1400 in all), and it is worth noting that because of the difference in temperature they flower almost two months later than in Kansai. Travel tip: visit Honshu in May for the fine weather, then enjoy a bonus of cherry blossom in Hokkaido.