Known at the 'Land that Time Forgot', Kunisaki is home to a large number of syncretic shrines and temples connected to the local Shugendo branch (japanvisitor blog)

One place I’ve always wanted to visit but have never managed is the Kunisaki Peninsula in Kyushu. It seems to have all the mysterious atmosphere and religious lore of Kumano and Shimane, with some stunning scenery too. Now one of my favourite writers, Stephen Mansfield, has written a revealing piece about the area in the Japan Times which has stimulated my determination even more to spend time in the area on my next trip south.

******************************************************

Kunisaki: into a world of moss and stone

BY STEPHEN MANSFIELD THE JAPAN TIMES JUL 12, 2014

The sense of antiquity on the Kunisaki Peninsula is immediate. There are those that believe the region — whose name is said to mean “land’s end” — was created by demons in the service of powerful gods. You have to take these accounts with a pinch of salt, of course, as each explanation confidently contradicts the others, but there is a palpable atmosphere of mystery here, upon which the imagination thrives.

Between A.D. 700 and 800 the region gave birth to a syncretic cult — a mix of Tendai School Buddhism, Shinto and mountain worship — known as Rokugomanzan. A holy man called Ninmon is credited with founding 28 of the cult’s temples on the peninsula, which became a training ground for devout worshipers.

Futagoji Temple is an important space for this worship and sits in the very center of the peninsula, at its highest point, surrounded by spokes of metamorphic rock in the form of volcanic ridges and valleys. Futago means twins, and the temple receives visits from the families of such children, which may explain the lack of visitors: such offspring are relatively rare.

The entrance steps to Futago-ji (courtesy walkjapan)

The temple’s two stone Nio-sama statues (guardians of the Buddha) stand menacingly beneath a canopy of giant ceders at the foot of an ancient stone path. Rustic figures, such as these two statues, are difficult to date by sight. One rare case is a pair of Nio-sama at nearby Iwatoji Temple, where an inscription on one of the figures reads “1478.” It is the closest we get to precise dating in a peninsula where time itself seems to have been put on hold.

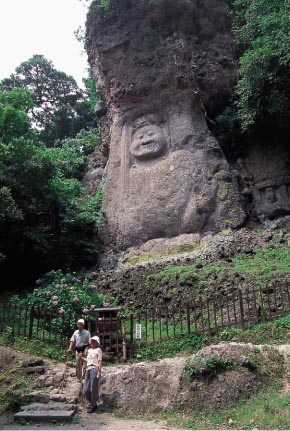

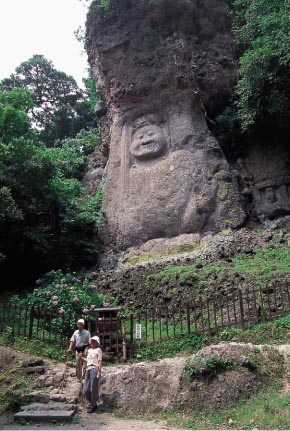

The region is best known for its massive bas-reliefs carved into rock faces. One of the most monumental is the Kumano magaibutsu, where there are two large Buddhist cliff carvings said to date from the eighth century. A defile in a gorge leads to Taizoji Temple, from where a steep stone path must be ascended to reach the figures. The going is rough but rewarding, with enough moss remaining on the stone path to suggest the absence of large numbers of visitors.

So old and seasoned are these stairs and implausibly large, stone figures that the natural and man-made are almost indistinguishable. A thousand years is a long time. Can things have changed that much here? If anything, the ageless carvings, timber structures and stone staircases look even more timeworn by the effect of weathering.

One of the many ageless stone carvings dotted around the region (tabisuke)

A local lord by the name of Atomo Sori, a Christian, did his best to deface the area’s Buddhist heritage but, mercifully, most of it has survived the vandalism that accompanied Sori’s religious zeal. The relative inaccessibility of many of the sites no doubt helped to keep them preserved.

Today the roads are well-surfaced, their condition maintained by the absence of traffic. With an infrequent bus schedule, it is best to have your own transportation. I had hoped to rent a motorbike, but ended up contacting Kunisaki Rental Car, a relatively new operation, based just outside the town of Kitsuki. At 8 a.m. sharp, a vehicle was delivered to my guesthouse, by, unexpectedly, a young Lithuanian. He was a trained engineer who worked for a company importing mechanical vehicles that had started renting its cars out.

Business was not brisk. Like others in the area who are connected to tourism, they were awaiting a surge in visitors that has yet to materialize. On the way to the office to complete the rental forms, he spoke garrulously, the torrent of words was a great relief, he said — he hadn’t met another foreigner for almost a year.

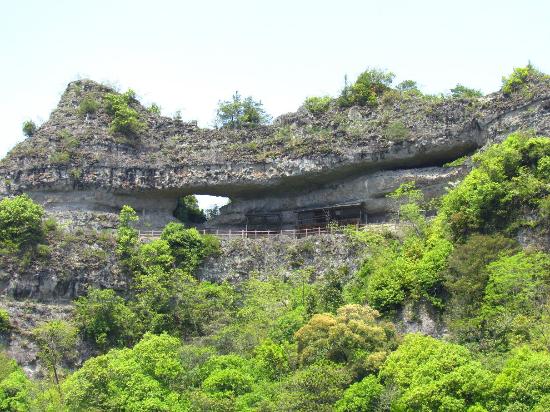

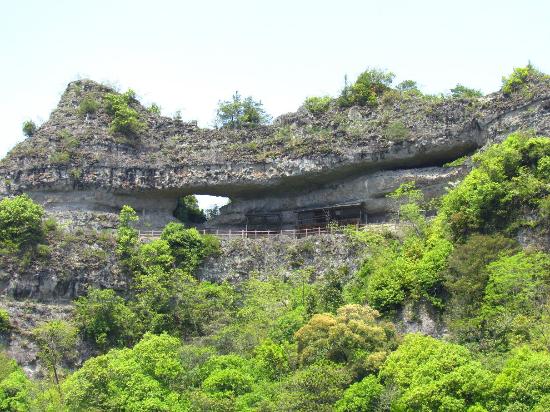

Once on the road, you discover that Kunisaki is good driving country, with plenty of twists and turns to keep you alert. The road cuts across open plains that funnel into narrow gorges, one particular landscape at the center of the peninsula reminded me of the limestone peaks of Laos, on a diminished scale. From the car window I could see the entrances to man-made caves, visible along shallow terraces that were somehow accessible via perilously steep escarpments. Beyond and above the neatly cultivated fields was wild country — the sort of landscape a person could vanish into.

Kumano magaibutsu on Kunisaki Peninsula. This eight-meter image of Fudo Myo-o, carved into the face of a rock cliff, is one of Japan's largest Buddhist stone images. (courtesy nipponia)

Why the deeper recesses of the peninsula are not more developed is puzzling given the cultural magnitude of the area. Kunisaki is a veritable Japanese holy land, said to contain more than half of Japan’s stone Buddhist statuary (and some of its oldest).

Like all sacred sites, life and death coexist in the physical structure of Kunisaki’s religious spaces. Many of the tombstones in the area’s smaller graveyards are engraved with the same family name, inferring a degree of custom and continuity — which still lives on — rarely seen in Japanese cities.

Perhaps the physical exertion required to reach the more remote sights and the proximity of leisure-oriented hot springs at nearby Beppu and Yufuin, explains the relative neglect of the area. You need the kind of fitness and muscularity possessed by pilgrims to negotiate the steep stone steps to the sacred sites deep in the Kunisaki peninsula. These ancient staircases, like hallways passing through dark green forests, have been buckled and distorted by time; their irregularity and the effort required to ascend them, reminds us of both the pace of the past and it’s material fabric.

But upon reaching these hidden sites, unanswered questions remained: Why make the carvings so difficult to access unless the effort required to reach them constituted — in the tradition of the great pilgrimages — an act of faith in itself?

Writer Donald Richie noted the almost unnatural darkness between the trees, comparing the shadows to black crepe strung between the giant cedars for a secret forest funeral. The drapes turned out to be shading nets, which created optimum conditions for growing mushrooms, but the point was made. These forests are dark, inducing a degree of fear, superstition and mystery.

Nature has been allowed to go its own way here, and the result is a richly biodiverse undergrowth, illuminated when filtered sunlight reaches the forest floor, lighting the funereal gloom like a stained-glass window in a chapel.

Richie’s travel essay on the region, “Kunisaki — Land’s End” (1991), includes a description of Fukiji, a tiny wooden temple built by the powerful Fujiwara clan, it dates back to the Heian era (794-1185). This is the oldest wooden temple in Kyushu and an incarnation of the peninsula’s antiquity. In fact, its main hall still contains the same carved image of Amida Buddha that Richie saw when he visited the temple a quarter century ago. “Behind him, festivities in the pure land he promised, painted on wood centuries ago and now spotted white — a leprous paradise,” Richie wrote. Little has changed in the intervening years.

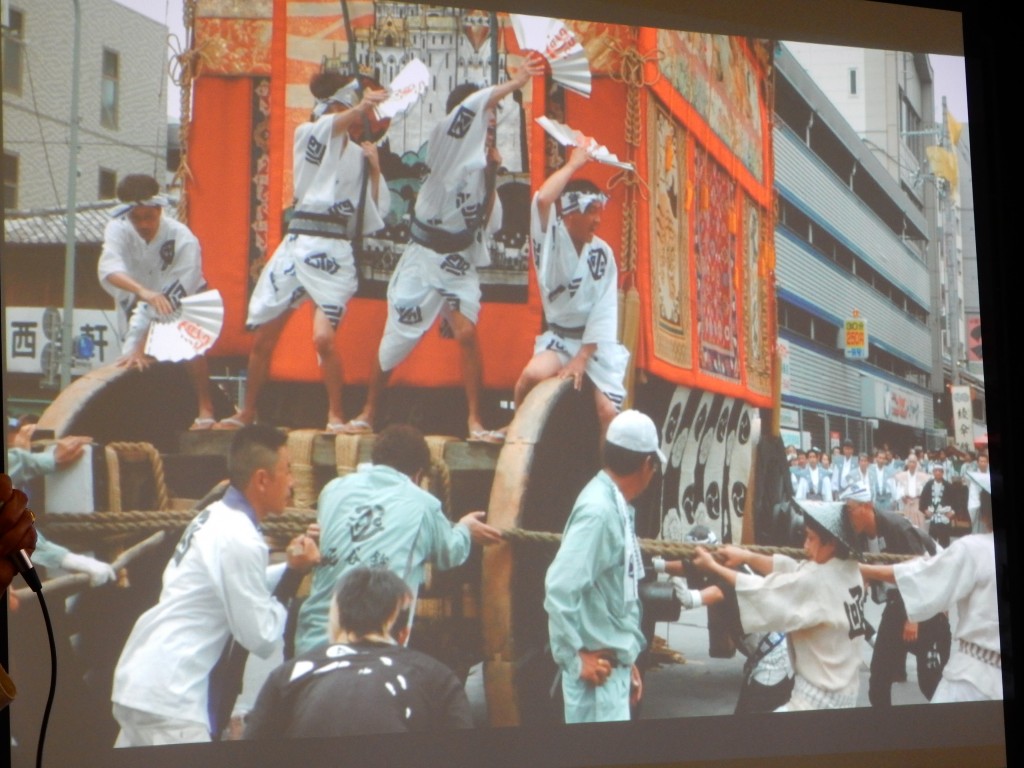

Even the annual Kebesu Festival in October at Iwakura Hachiman Shrine in Kunisaki City, strikes the visitor as more elemental than Japan’s other, more managed, rituals. Men in grotesque, earth-stained masks attempt to dash into a sacred fire guarded by white-clad figures holding burning ferns. It is a rite that might easily have been staged in a village grove in Papua New Guinea.

(courtesy trip advisor)

I depended on my feet for the last two days in the peninsula, cohabiting with snakes, wood pigeons and wild deer. Where trainee mountain monks would once have used straw sandals, I wore a pair of clodhopper boots, no doubt making the going a lot easier.

Pilgrimages and holy journeys are often synonymous with healing, both spiritual and physical. With feet about to form suppurating blisters, I sought out temporary relief on my last afternoon at Akane-no-sato, a calcium-sulfur spring in the small town of Kunimi. It would have been pleasant to share the views of forested mountains with other bathers, but there wasn’t a soul in sight.

The tour buses will eventually materialize, of course, and the parking lots they build to accommodate them will be as large as rice paddies, but for the moment, we can partake of Kunisaki’s untroubled timelessness, even without entirely grasping its meaning and correspondences. This place is as it should be — leaving a little something unexplained, some mysteries still intact.

*************************************************

Getting there: Kitsuki and the other towns in Kunisaki can be reached by irregular buses and trains from Beppu or Fukuoka. Flights to nearby Oita airport leave Tokyo and Osaka daily.