Shinto priest, Florian Wiltschko (source unknown)

Green Shinto has carried an article on Japan’s first full-time foreign priest before. Now the young Austrian, Florian Wiltschko, has featured in a Japan Times article. Clarification should be made here that, contrary to the news report, he is not the first foreigner to qualify and work as a Shinto priest in Japan (see here and here for predecessors). He is, however, the first foreigner to go through the officially licensed Jinja Honcho qualification process and get a full-time job at a Jinja Honcho shrine.

Reference to the ‘blue-eyed priest’ brings to mind the ‘blue-eyed samurai’ Will Adams, who was also a pioneering figure and fluent in Japanese. But whereas Will Adams was the only ever Western samurai, the expectations are that Wiltschko will be followed by others. Nonetheless his dedication, determination and fluency in Japanese are an indication that his trailblazing will be no easy act to follow.

**********************************************************

Florian Wiltschko, priest at Konno Hachimangu in Shibuya, downtown Tokyo (Photo Mami Maruko)

Blue-eyed Austrian finds calling at shrine

27-year-old Florian Wiltschko is Japan’s first foreign Shinto priest

BY MAMI MARUKO Japan Times JUN 10, 2014

Walking through the torii, or gateway, to the quiet and serene Konnoh Hachimangu Shrine in Tokyo’s Shibuya Ward — minutes away from the hustle and bustle of Shibuya’s main “scramble crossing” — and being welcomed by a blond and blue-eyed Shinto priest seems almost surreal.

But once Florian Wiltschko starts talking, it is easy to forget that he is an Austrian, and that he started his career at the shrine two years ago. “It was a calling,” says Wiltschko, a “gonnegi,” or priest, in a clear-toned voice.

Wiltschko, 27, is the first foreigner in Japan to become a Shinto priest. “Walking this path (of Shintoism) has not been so easy, but there are many more days when I feel unparalleled joy in having chosen this job, and being able to continue this job,” he says in fluent Japanese.

Although Wiltschko put a lot of time, energy and study into becoming a priest, he says he didn’t intend to become one at first but the idea came quite naturally to him. Born and raised in Linz, the third biggest town in Austria, Wiltschko had no connection to Japan at all before paying his first visit to the country in 2002, at age 15, when he accompanied his father, a geography teacher, on a sightseeing tour.

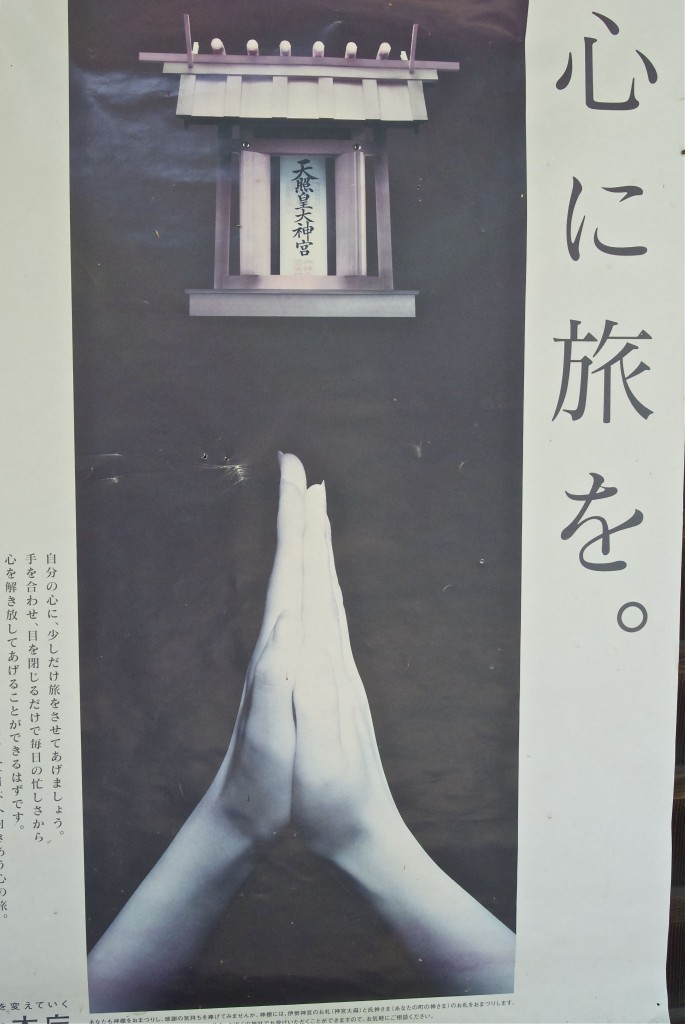

During his first visit, he bought a Shinto altar because he thought it was an interesting object, and installed it in his home back in Austria. That altar, he says, was the beginning of his connection to Shintoism. “I would pray every day at the altar, and that made me feel closer to Shintoism,” he recalled.

Taking more interest in Japan and reading many books about its history, culture and literature, he returned to visit several more times, and gradually became more intrigued with the world of Shintoism. After graduating from high school in his hometown, he served in the army for nine months, and then came to Japan to serve an apprenticeship at a shrine in Aichi Prefecture.

"While it may not be much to look at now, Konno Hachimangu shrine was once the site of the household that’s believed to give the area its name: the Shibuya family." (Caption and photo by Time Out Tokyo)

He then went back to Austria to study Japanology at the University of Vienna, where he read a lot of books on the country, including Kojiki (“Records of Ancient Matters”), which he read in its original form, in Japanese. He later returned to Japan to study Shintoism at Kokugakuin University in Tokyo. “I chose this route, because I heard this was the fastest way to take up Shintoism as a career,” Wiltschko says.

Immediately after graduating, he began working at Konnoh Hachimangu Shrine, which is run by the family of a former classmate of his at Kokugakuin. He says his parents have always been supportive, never judging or questioning his choice to become a Shinto priest.

As their only child, he imagines that his parents must have been worried that he lived so far away. But having seen their son work contentedly as a priest, he says they are now happy for him. “I try to visit Austria from time to time, but whenever I plan something, my parents come to visit me in Japan instead,” he says, laughing, adding that during his parents’ last visit, they saw the place where he was living and working at the shrine and they seemed to be relieved that he had found such a nice environment, surrounded by kind colleagues.

Wiltschko wakes up at 5:30 a.m. along with his fellow priests and does chores around the shrine, such as cleaning the rooms and the grounds, and preparing breakfast to offer at the altar. During the day, he offers different kinds of “matsuri,” or festivals, at the shrine.

Sweeping the shrine and grounds is part of a priest's duties, as are making the daily offerings to the kami

“Humans can live peacefully, because “hachiman sama” (deity) is always beside us. One of my biggest roles as a Shinto priest is to protect this place, so that people who visit the shrine can feel close to this land’s deity. We make every effort to keep the place clean, bright, and refreshing,” he says.

That is why the young priest laments the fact that some Japanese don’t care to worship and give a prayer to the guardian deity when they visit the shrine. “Some people just stop by at the shrine to have tobacco or a bento (boxed lunch), which is very sad,” he says, adding that he would like the Japanese to regain their common sense and conscience to protect and live in harmony with nature, which is deeply embedded in its culture.

Noting the shrine’s long history — 923 years — he says that it might be “an ideal environment, where the traditional spirit of Japan can still be encountered. “I feel grateful to be here. I do have an iPhone, but I can feel and go back to nature whenever I clean up the place,” he says.

Wiltschko is often asked why he doesn’t attain Japanese citizenship because of his devoted attitude toward his career and fluent Japanese, he says. But he doesn’t place any importance on nationality, and thus changing nationality doesn’t mean anything to him.

Although his colleagues jokingly tell him “today your eyes are blue as usual,” he says he normally doesn’t have any consciousness that he’s Austrian, especially in an environment where “no one talks about nationality.” He says he will continue to be a Shinto priest for the rest of his life.

“I look forward to finding out what I can do with my career in the future. Perhaps I can nurture or educate the next generation through my career and activities at the shrine,” he says. “I don’t have any grandiose vision, like I want to change Japanese society or the shrine or something,” Wiltschko says. “But I just want to devote myself to my career, enjoy the process of developing as a human being, and see where I end up.”

Despite its picturesque, rocky coastline, Iki’s geography is characterized by gently rolling hills — the highest peak reaches just 212 meters.

Despite its picturesque, rocky coastline, Iki’s geography is characterized by gently rolling hills — the highest peak reaches just 212 meters.