The following is couched in academic terms but is highly relevant to the purpose of Green Shinto as it concerns sacred trees, spirituality and the environment. It is a call for papers for a workshop to be held in France, and its conclusion is worth noting: “in order to preserve the forest, it must be made a resource for well-being, biodiversity, resourcing, utopia, spirituality perceived as useful by humanity.”

*******************

by Christine Vial Kayser

The aim of this workshop is to initiate a reflection on the dynamics of the relationship to the forest – and, beyond that, to nature – in Asia, its cultural and universal, physiological and emotional determinants. We start from the example of the Japanese practice of immersion in a forest called Shinrin-yoku or “forest bath” (or sylvotherapy), a practice born in Japan in the 1980s, following the same studies of the benefits of “green” landscapes developed in the United States (Wilson 1984). These studies focus on the physical or psychological benefits but do not question possible non-physiological or psychological causes: cultural (imaginary of the tree), mnemonic and emotional causes, nor do they have a comparative perspective.

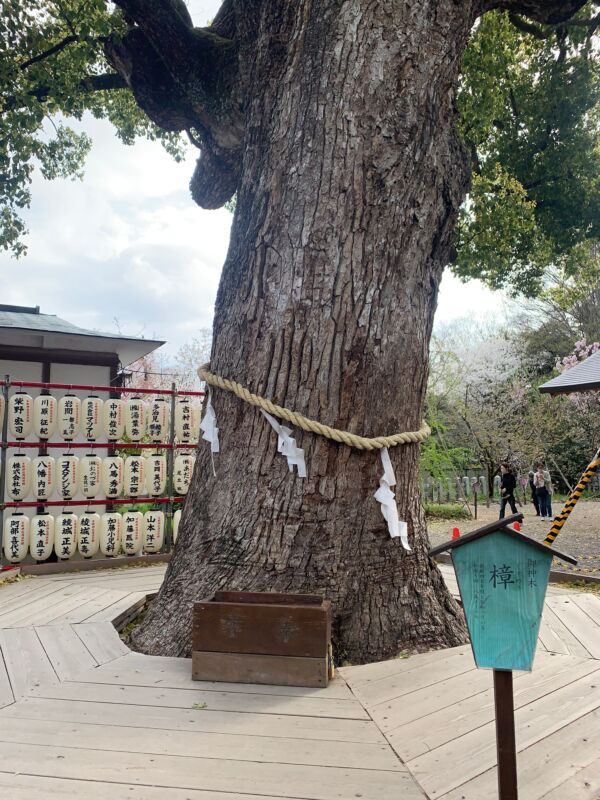

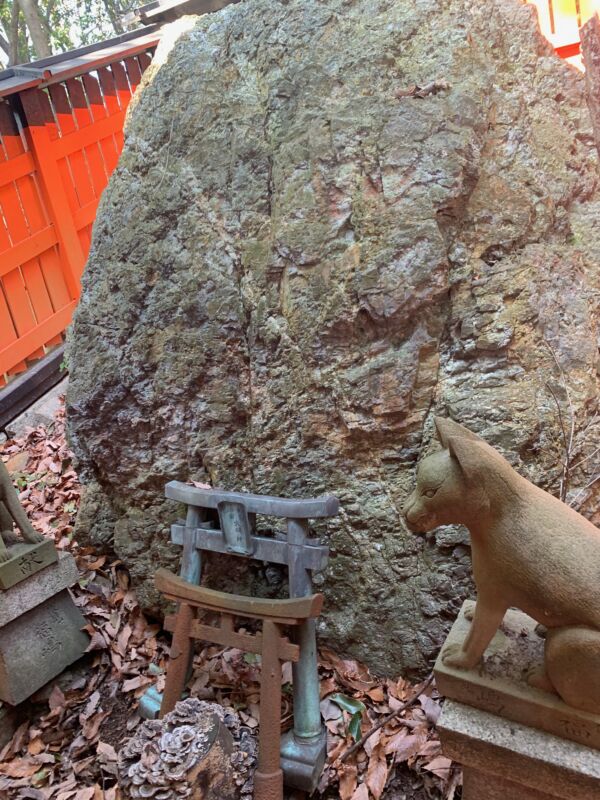

In Asia the practice could have animist (Knight 2009) or even Buddhist roots. They may take form within the concept of qi (ki) or vital energy shared between man and nature as well as the specific perception of trees in Asian philosophy (Bao et al. 2016; Escande 2011; Alban & Berwick 2004). Won Sop et al. highlight the traditional Korean combination of wood, stone and water to explain the health benefits of ‘forest baths’ in Korea (Won Sop et al. 2010). The representation of the Yakshini also testifies to the role of the tree as a source of life, sometimes ambivalent, in the Indian tradition, where certain species of trees are still considered sacred today. Such representations can be found in Europe before the revolution of modernity, or in the 19th century in European Romanticism (Harrison 1992) or in American transcendentalism (Egerton 2011).

The workshop will therefore examine in Asia in general, and in a comparative dimension with the West, the subjective representation, “for oneself”, of the forest that is formed during the experience, how this interferes with the representation of the forest “in itself”, as an external and autonomous object. We will ask whether the representation of trees in arts and culture sheds light on what happens during immersion in the forest: what is the role of previous images, whether literary, visual, taken from the world of art, visual culture, religious representations; traditional or contemporary (video games, multimedia installations). Indeed, the public’s fascination for these immersive practices in the forest is accompanied by the same thirst for immersive digital practices, as shown by the installation of the Japanese collective Team Lab (Tokyo) whose installations at the Mori Museum or in heritage forest locations (A Forest where gods live at Mifuneyama Rakuen Park) will soon be exhibited in Amsterdam (Huw 2020). This suggests that these installations, by certain aspects (interactivity, sense of “flow”) are perceived as “magical” (Jeon 2019).

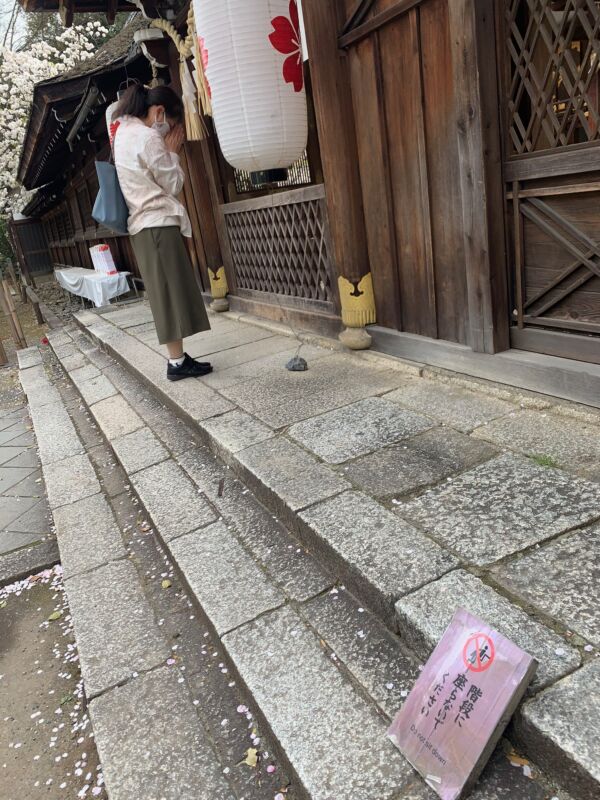

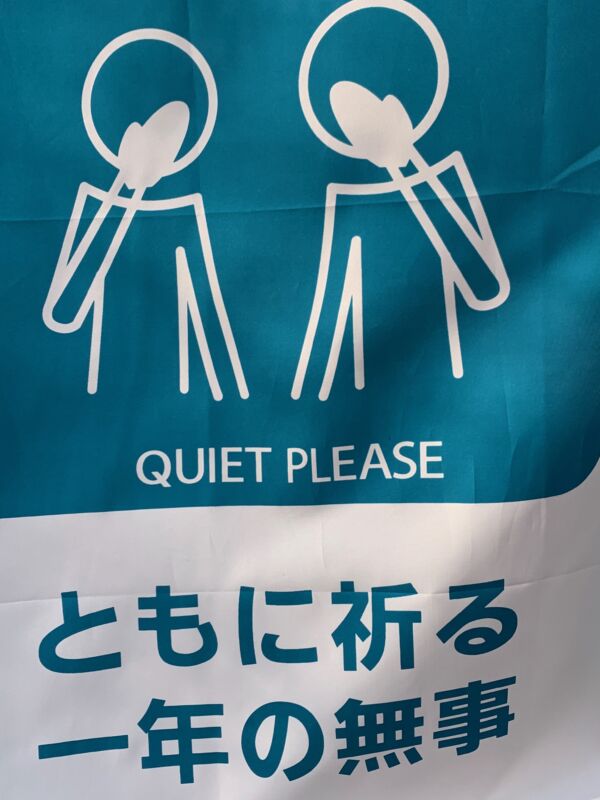

The need for silence during the practice of “forest bathing”, presented by practitioners of the discipline as a way to listen to the mind-body relationship, is perhaps a way of being in contact with these imaginary elements. Decorating a tree in a ritual, immersing oneself in a video installation (despite its ambiguities) also. Conversely, the perception of the tree as a trunk to be felled extinguishes this plural dimension. It is also possible that the impression of unity between the inner world and the environment may have repairing properties of the Lacanian “fragmented body”, through sensitive experience (Kono 2011).

The objective is to understand, through a multidisciplinary cultural approach, the dynamics of the relationship to trees in Asia, and how cultural approaches can, possibly, contribute to the protection of trees and biodiversity. We postulate that in a “post-anthropocene”, ecological perspective, it is necessary to “re-enchant” the tree and the forest (as Bruno Latour suggests; Où suis-je, 2021; Face à Gaïa, 2015). Seeing the forest as a living space, an “Umwelt” of which we are only a part, and not as a “world” in which man shapes his habitat. Such a reversal of perspective, implied in the Japanese concept of satoyama, is itself a (re)construction (Indrawan et al. 2014) and can be critically approached, underlining its ambiguities (Rots 2014; Knight 2010). Indeed, it appears that for humans nature is always perceived as a resource (Descola 2005). We propose to explore the idea that in order to preserve the forest, it must be made a resource for well-being, biodiversity, resourcing, utopia, spirituality perceived as useful by humanity. For that the sensory and imaginative approach to nature must be associated with the dominant mechanistic-rationalist approach (Beau 2020).

These different aspects will be questioned in a comparative and in a critical perspective, eschewing essentialism, and possibly showing the limits of this hypothesis in the face of competing competition between nature and man.

For those participants who wish, an immersion experience guided by a professional of Shinrin Yoku will be proposed in the forest of Fontainebleau (fee required).

Practical details

The workshop will take place in person and by videoconference at INHA, unless the pandemic still prohibits all meetings. Communications will be in French and English.

Proposals in the form of an abstract of 300 to 500 words must be received by April 30 at contact@asie-sorbonne.fr. Successful participants will be notified by May 30. A publication of a selection of the contributions is planned.

Bibliography

– Alban N., Berwick C. (2004), Forêt et religion au Japon, Environnement Culture et Société (6). OA.

– Bao Y., Yang T., Lin X. and al. (2016), Aesthetic Preferences for Eastern and Western Traditional Visual Art: Identity Matters, Frontiers in Psychology, Doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01596. OA

– Beau F. (2020, 14 Sept.) Une esthétique du soin environnemental pour cultiver la légèreté, in A. Foiret, « Art et écologie : des croisements fertiles? », Plastik, n° 9. http://plastik.univ-paris1.fr/quest-ce-que-lart-apporte-a-lecologie/

– Descola P. (2005) ; Par-delà nature et culture, Paris, Gallimard.

– Egerton F. (2011), History of Ecological Sciences, Part 39: Henry David Thoreau, Ecologist, Bulletin of ecological society of America. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9623-92.3.251

– Escande Y. (2011), L’arbre en Chine, in J. Pigeaud, L’arbre ou la raison des arbres, PUR.

– Harrison R. (1992). Forest: Shadow of civilization, Chicago, The University Of Chicago Press.

– Huw O. (2020, sept.), Europe is getting a teamLab art space, and it’s going to be mindblowing, Time Out. Online: https://www.timeout.com/news/europe-is-getting-a-teamlab-art-space-and-i…

– Knight C. (2009, dec.), “Between the profane and the spirit worlds: the conceptualisation of uplands and mountains in Japanese and Maori folklore”. New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies, vol. 11, n°2.

– Knight C. (2010), The concept of satoyama and its role in the contemporary discourse on nature conservation in Japan, Asian Studies Review, 34(4), 421 (December 2010)

– Indrawan M., Yabe M., Nomura H., Harrison R. (2014, March). Deconstructing satoyama – The socio-ecological landscape in Japan (science direct) show that satoyama is cultural social construct, Ecological Engineering, vol. 64, pp. 77-84.

– Jeon M., Fiebrink R., Edmond E., Herath D. (2019, Nov.). From rituals to magic: Interactive art and HCI of the past, present, and future, International Journal of Human-Computer Studies (131):108-119.

– Kono T. (2011). Ecological Self: Body and Affordances, Kyoto, Nakanishiya publisher (in Japanese).

– Rots A. (2014). Does Shinto offer a viable model for environmental sustainability? Excerpts from author’s PhD. Online Academia.

– Wilson E. (1984). Biophilia. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press.

– Won Sop S., Poung Sik Y., Rhi Wha Y., and Chang Seob S. (2010, Jan.). Forest experience and psychological health benefits: the state of the art and future prospect in Korea, Environ Health Prev Med; 15(1): 38–47. Doi: 10.1007/s12199-009-0114-9Contact Info: