Japan has some of the harshest punishments for cannabis use in the world. One might presume this stems from the country’s dedication to hard work and efficiency, but it’s rather the legacy of the US occupation after WW2. In fact, historically the country has been very favourable to growing cannabis, and 160 kilometers north of Tokyo is a dedicated museum to the subject run by Takayasu Junichi.

The Japan Times carries a lengthy interview with the museum head today, in which its use in Shinto is touched upon. It’s a topic that Green Shinto has covered previously in a posting entitled High on Hemp. Hemp and mariujana, incidentally, come from two different types of the cannabis plant. (The following is an extract; for the full Japan Times article, please see here.)

************************************************************

Cannabis: the fiber of Japan BY JON MITCHELL (Japan Times)

Priestess with a head band made of hemp

“Most Japanese people see cannabis as a subculture of Japan but they’re wrong,” Takayasu says. “Cannabis has been at the very heart of Japanese culture for thousands of years.”

According to Takayasu, the earliest evidence of cannabis in Japan dates back to the Jomon Period (10,000-200 B.C.), with pottery relics recovered in Fukui Prefecture containing seeds and scraps of woven cannabis fibers. “Cannabis was the most important substance for prehistoric people in Japan,” he says. “They wore clothes made from its fibers and they used it for bow strings and fishing lines.”

It is likely that the variety of cannabis from which these Jomon Period fibers originated was cannabis sativa. Tall-growing and valued for its strong stems, it is from sativa strains that today’s specially bred industrial hemp is derived.

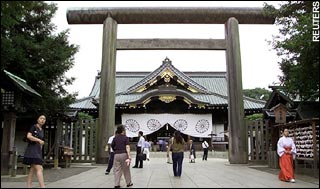

In the following centuries, cannabis continued to play a key role in Japan — particularly in Shintoism, the country’s indigenous religion. Cannabis was revered for its cleansing abilities so priests used to wave bundles of its leaves to bless believers and exorcise evil spirits. This significance survives today with the thick ceremonial ropes woven from cannabis fibers that are displayed at shrines. Shinto priests are also known to decorate their wands with strips of the gold-colored rind of cannabis stalks.

Cannabis was also important in the lives of ordinary people. According to early 20th-century historian George Foot Moore, Japanese travelers historically used to present small offerings of cannabis leaves at roadside shrines to ensure safe journeys. He also noted how, during the summer Bon festival, families burned bundles of cannabis in their doorways to welcome back the spirits of the dead.

At Obon people used to burn bunches of cannabis to call back the dead

Until the mid-20th century, cannabis was cultivated all over Japan, particularly in Tohoku and Hokkaido, and it frequently cropped up in literature. As well as references to cannabis plants in ninja training, they also feature in the “Manyoshu” — Japan’s oldest collection of poems — and the Edo Period (1603-1868) book of woodblock prints, “Wakoku Hyakujo.” In haiku poetry, too, key words describing the stages of cannabis cultivation denoted the season when the poem is set.

“Cannabis farming used to be a year-round cycle,” Takayasu says. “The seeds were planted in spring then harvested in the summer. Following this, the stalks were dried then soaked and turned into fiber. Throughout the winter, these were then woven into cloth and made into clothes ready to wear for the next planting season.”

With cannabis playing such an important material and spiritual role in the lives of Japanese people, one obvious question arises: Did people smoke it?

Takayasu, along with other Japanese cannabis experts, isn’t sure. Although historical records make no mention of the practice, some historians have speculated that cannabis may have been the drug of choice for commoners. Whereas rice — and the sake brewed from it — was monopolized by the upper classes, cannabis was grown widely and was freely available.

Some scientific studies also suggest high levels of psychoactive tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) in cannabis plants in Japan. According to one survey published by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime in 1973, cannabis plants from Tochigi and Hokkaido clocked THC levels of 3.9 percent and 3.4 percent, respectively. As a comparison, the University of Mississippi’s Marijuana Potency Monitoring Project revealed that average THC levels in marijuana seized by U.S. police in the 1970s were only around 1.5 percent.

Nor are Japanese people averse to taking advantage of the medicinal benefits of cannabis. Long an ingredient in traditional Chinese medicine, cannabis-based cures were available from Japanese drug stores to treat insomnia and relieve pain in the early 20th century.

However, the 1940s — in particular, World War II — marked a major turning point in the story of Japanese cannabis production.

One of the few licensed farms allowed today in Tochigi, Tohoku (photo by Takaysu Junicihi)

At first, the decade started well for farmers. “During World War II, there was a saying among the military that without cannabis, the war couldn’t be waged,” Takayasu says. “Cannabis was classified as a war material, used by the navy for ropes and the air force for parachute cords. Here in Tochigi Prefecture, for example, half of the cannabis crop was set aside for the military.”

Following the country’s defeat in 1945, however, the U.S. authorities occupying Japan brought with them American attitudes toward cannabis. Washington had effectively outlawed cannabis in the United States in 1937 and now it moved to ban it in Japan. In July 1948, with the nation still under U.S. occupation, it passed the Cannabis Control Act — the law that remains the basis of anti-cannabis policy in Japan today.

There are a number of different theories as to why the U.S. outlawed cannabis in Japan. Some believe it was based upon a genuine desire to protect Japanese people from the evils of narcotics, while others point out that the U.S. allowed the sale of over-the-counter amphetamines to continue until 1951. Several cannabis experts argue that the ban was instigated by U.S. petrochemical interests in a bid to shut down the Japanese cannabis fiber industry, opening the market to man-made materials such as polyester and nylon.

Takayasu locates the cannabis ban within the wider context of U.S. attempts to reduce the power of the Japanese military. “In the same way that U.S. authorities discouraged kendo and judo, the 1948 Cannabis Control Act was a way to undermine militarism in Japan,” he says. “The wartime cannabis industry had been so dominated by the military that the Cannabis Control Act was designed to strip away its power.”

Whatever the motivation, the U.S. decision to prohibit cannabis created panic among Japanese farmers. In an effort to calm their fears, Emperor Hirohito visited Tochigi Prefecture in the months prior to the ban to reassure farmers they would be able to continue to grow in defiance of the new law — a surprisingly subversive statement.

For several years, the Emperor’s reassurances proved true and cannabis cultivation continued unabated. In 1950, for example, there were approximately 25,000 cannabis farms nationwide. In the following decades, however, this number plummeted. Takayasu attributes this to a slump in demand caused by the popularity of artificial fibers and the costs of the new licenses cannabis farmers were required to possess under the 1948 act.

Nowadays, Takayasu said, there are fewer than 60 licensed cannabis farms in Japan — all of which are required to grow strains of cannabis containing minimal levels of THC.

************************************************

For a piece on Japan’s 2nd Annual Hemp Festival, see here.