Following on from the posting about the Sounds of Shinto, a piece in the Huffington Post suggests that sound may also have played a part in the spirituality of Stonehenge. The article is of interest because rocks and megaliths are such a prominent part of Shinto. They are prominent too in Japan’s ‘power spots’, as demonstrated by Kara Yamaguchi in her writing.

The relationship of Shinto’s rocks to ancestor worship has been explored in earlier Green Shinto postings, such as this one, so it’s of interest that Stonehenge may also have been a place of burial and ancestral rites. The idea of Shinto kami descending to earth in rock-boats may not be so far-fetched when one thinks of life originating from meteors and the way that meteorites fall to earth from distant heavens.

If one puts the potency of rock together with the significance of a circle (recalling the circular mirrors in Shinto shrines), one can begin to understand why Stonehenge had such symbolic force for the ancient humans who spent so much time and energy to construct it. The circle is the most powerful of forms, resonant with meaning, and it is surely no coincidence that the souls of the dead were regarded as spherical discs of light in ancient China.

Erected all those thousands of centuries ago, the stone circle of Stonehenge continues to haunt the imagination and be a focus for spiritual ceremonies. That the stones may have had voices that were listened to by the people of the past is a fascinating concept. May it forever rock on!

********************************************************

Druid rite at Stonehenge (courtesy Kovasck)

(The following is copyright 2014 LiveScience, a TechMediaNetwork company. All rights reserved.)

Researchers recently had the rare chance to thwack the giant megaliths at Stonehenge and noted that they each resonated with sounds like those of metallic or wooden bells. They proposed that the strange monument was once either an ancient long-distance communication system, or a Stone Age church bell system.

But despite centuries of speculation, scientists aren’t much closer to revealing why the enigmatic monument was raised on the Salisbury plain in England thousands of years ago. Legends ascribe the site to Merlin’s wizardry, and conspiracy theorists have credited aliens and UFOs for the megaliths. Meanwhile, scientists propose more grounded theories about the site. From giant musical instrument to elite burial ground, here are seven of the most popular theories about why Stonehenge was built.

1. Sacred hunting ground

The area around Stonehenge was a hunting ground along an ancient auroch [extinct kind of cattle] migration route thousands of years before the first stones were raised, according to archaeological evidence. A site just a mile away from the megaliths contains evidence of human occupation spanning 3,000 years, including thousands of auroch bones, flint tools and evidence of burning.

The Stonehenge site itself bears evidence of construction as far back as 8,500 to 10,000 years ago, when a few pine posts were raised to create an ancient structure. This archaeological evidence hints that the site was originally an ancient hunting and feasting site, and perhaps the megaliths were raised to memorialize the meaty bounty.

2. Unity monument?

Some believe the British megaliths were erected to celebrate peace and unity. During the monument’s period of intense building, between 3000 B.C. and 2500 B.C., the culture of the British isle was increasingly unified, a fact exemplified by more uniform pottery styles taking hold throughout the region. The massive endeavor would have taken thousands of laborers and employed stones from far-flung Wales. Working on such a big collaborative project would have been a unifying exercise on its own.

Does Shinto's love of rocks stem from the connection with death and ancestral spirits?

3. Astronomical calendar

Many believe the ancients celebrated winter solstice at Stonehenge. The avenue near Stonehenge is aligned with the winter solstice sunset, and nearby archaeological evidence suggests that pigs were slaughtered during December and January — possibly for a mid-winter feast. The site also faces the sunrise during the summer solstice, and thousands of visitors still flock to the site every year to celebrate at that time.

4. Stonehenge sound illusion

Two pipers playing in a field around Stonehenge would have the sounds canceled out at certain spots, a sound illusion that may have inspired Stonehenge builders, according to a presentation given at the 2012 American Association for the Advancement of Sciences meeting. The megaliths might have been raised to augment the area’s natural sound cancellation, with the boulders selectively blocking sound. In fact, the monument is often nicknamed “The Piper’s Stones” in England, and legend holds that magic pipers led maidens to the field, and then turned them into the stones present today. Even those who don’t buy the sound illusion theory don’t deny that Stonehenge had amazing acoustics, with the cavernous echoes typically found in a lecture hall or a cathedral.

5. Elite cemetery

The mysterious monument may have once been a burial ground for the elite, according to one study. Thousands of skeletal fragments from at least 63 individuals have been exhumed from the area, with an equal proportion of men, women and children found there. The burials date to 3000 B.C., as construction of the monument was getting started. Archaeologists have also unearthed a possible incense bowl and a mace head, an object usually associated with the elite in ancient society.

6. Giant bells

The newest theory suggests the dolerites and sarsens at Stonehenge produce unique, subtly different sounds similar to hollow wooden or metallic bells. Because the sounds would have carried over long distances, these sounds could have been a form of primitive communication, or alternatively, they may have been used much as church bells are today. The idea of using rocks to make music isn’t new; many other cultures have employed lithophones — essentially giant xylophones that produce unique sounds.

7. Healing site

Many of the skeletons buried near the site bear marks of illness or injury, leading Geoffrey Wainwright and Timothy Darvill to propose the site was a spot for ancient healing. Lending credence to that theory, many of Stonehenge’s bluestones have been chipped away over the ages, perhaps by long-lost pilgrims seeking protective or healing talismans from the location. Of course, Stonehenge may have built for many, some or none of these reasons, and odds are no one will ever know for sure.

Shamanistic rock worship is common in Korea, where rocks are seen as part of the native mountain worship

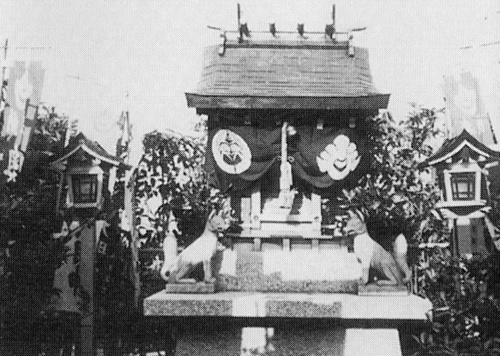

There are several reasons for thinking that Inari may be the most suitable kami for spreading to the West. Of the three most common kami in Japan – Hachiman, Tenjin and Inari – Inari okami is most clearly animist in nature. The kami’s association with fertility has a universal orientation, moreover the male-female ambivalence fits in nicely with neo-pagan strivings for gender balance (Inari traditionally manifests either as a young woman or an old man).

There are several reasons for thinking that Inari may be the most suitable kami for spreading to the West. Of the three most common kami in Japan – Hachiman, Tenjin and Inari – Inari okami is most clearly animist in nature. The kami’s association with fertility has a universal orientation, moreover the male-female ambivalence fits in nicely with neo-pagan strivings for gender balance (Inari traditionally manifests either as a young woman or an old man).