Since Heian times gagaku has been considered the music of the gods

A couple of years ago I went to a talk about sounds used for healing purposes which involved Tibetan singing bowls. That sounds affect the human psyche is obvious enough when one thinks of how certain kinds of music can move us to tears, yet other sounds induce panic and alarm. There are sounds too that can cause irritation or acute stress. Even human language itself can be affective, as the very different responses to French and German attest.

Musician Graham Ranft, presently studying the Ryuteki (the flute used in gagaku pictured above), has written in from Australia with some interesting observations he has come across regarding the use of sound in Shinto. These extend the notion of kotodama (word soul), by which certain words or sounds are thought to have magical properties (like the Middle Eastern word abracadabra).

The quotations below are drawn from “Japanese spirituality and music practice: Art as self-cultivation” by Koji Matsunobu.

The indigenous Japanese religions presented an animistic view of sound appreciation. It was believed that every sound bore a spirit, and people could be enlightened through any sound. Two important concepts regarding this view are otodamaho and ichion-jobutsu [the attainment of enlightenment through perfecting a single tone]…

The concept of otodamaho in Shinto is a method of purifying the body and mind

through the esoteric power of sound. A Japanese animist belief that was traditionally shared by people in ancient Japan explains that spiritual power resides in all sounds, including natural sound and spoken words. Otodamaho suggests that spiritual practitioners become engaged in a meditative process through the appreciation and embodiment of natural sounds, situating themselves in nature to become part of the universe.Yoshisane Tomokiyo (1888–1952), an institutor of a new sect of Shinto,

elaborates on the theory of spiritual sound based on the concept of otodamaho as follows: “Nothing is more magical than the spirit of sound. All things in this universe are caused by the spirit of sound. All lives flow with the spirit of sound”.To grasp this perspective, Tomokiyo recommends that one simply listen to a “sound.” Simply listen to a certain sound quietly and calm down. That’s all…. You do not have to listen to music. Listen to a certain unchangeable sound: the sound of a waterfall, the murmur of a brook, [the] sound of rain, the sound of waves, anything you like.

It turns out then that one reason why silence is golden is because it allows us to listen to the Sound of Nature. So drop out, turn off and tune in to those Good Vibrations the Beach Boys were singing about all those many years ago. And we look forward to further reports from Graham in his quest to pursue a Shinto spirituality through the resonance of sound.

********************************************************

To read more about the above concepts in regard to shakuhachi, please click on this page and scroll down to the text.

To read more about Sound Healing, please see this page.

The sounds of nature can have a healing effect

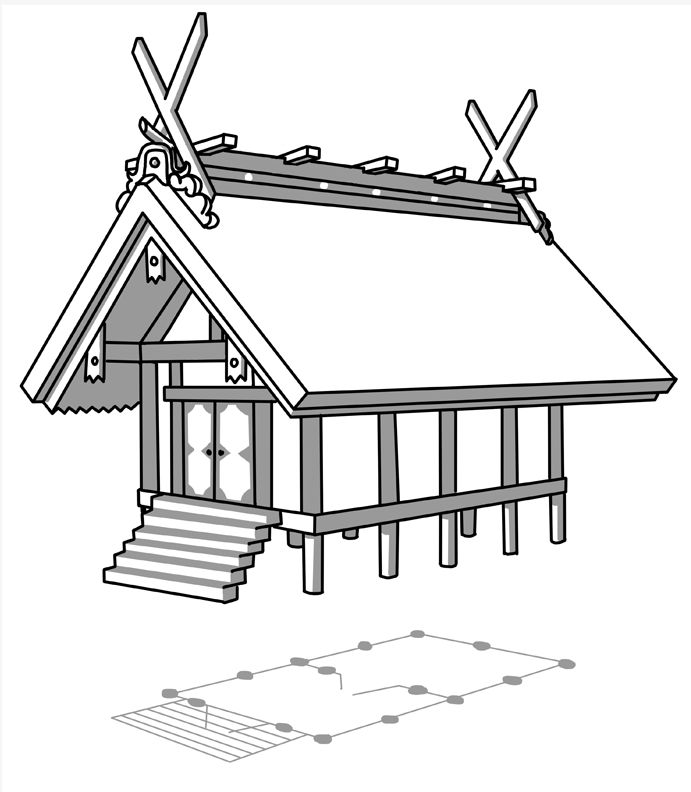

Kasuga-zukuri:

Kasuga-zukuri:

March 17, 2014 The Yomiuri Shimbun

March 17, 2014 The Yomiuri Shimbun

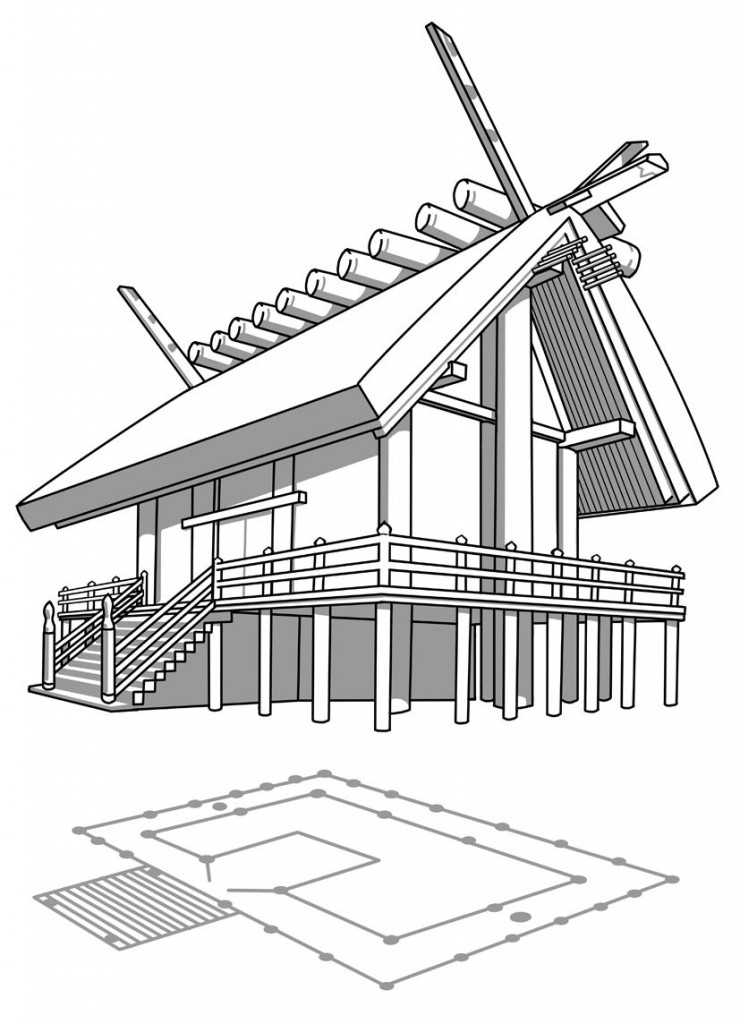

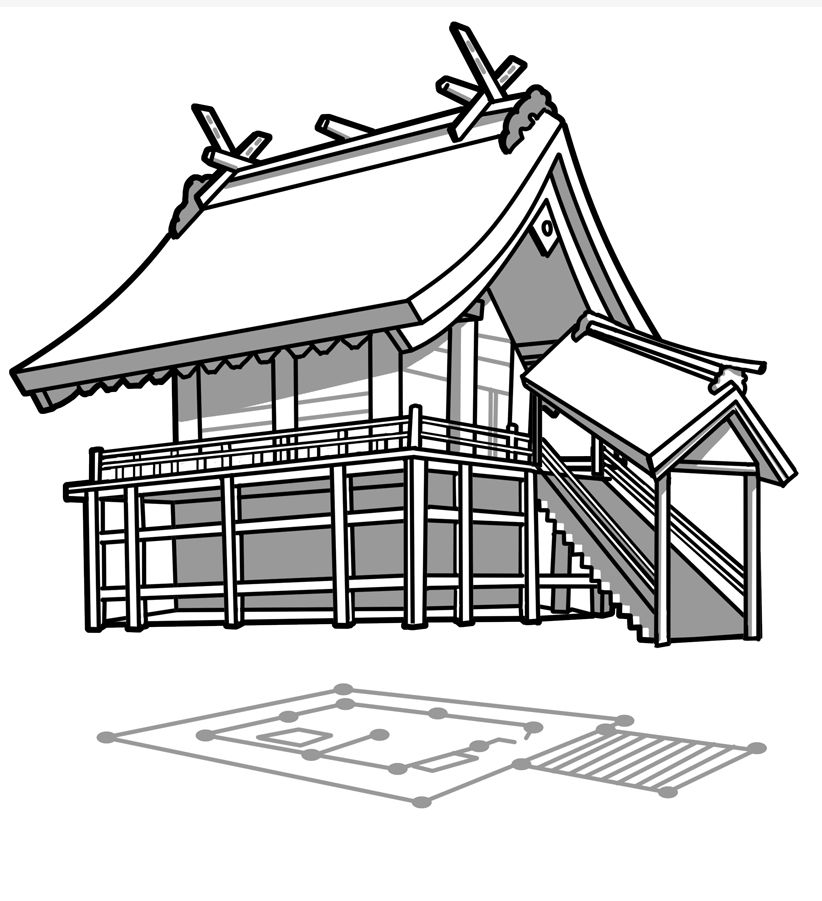

Shinmei-zukuri: A type of construction associated with the rice storehouse and dating from the Yayoi period. A decorated bronze mirror from the fourth century depicts a similar style of building. It is a structure raised on stilts, with the floor level several feet above ground. It uses round wooden pillars between which boards are laid horizontally to form the walls.

Shinmei-zukuri: A type of construction associated with the rice storehouse and dating from the Yayoi period. A decorated bronze mirror from the fourth century depicts a similar style of building. It is a structure raised on stilts, with the floor level several feet above ground. It uses round wooden pillars between which boards are laid horizontally to form the walls. Taisha-zukuri: A type of honden building that probably derived from the house (miya) of the village headman, who was responsible for performing rites for the kami.

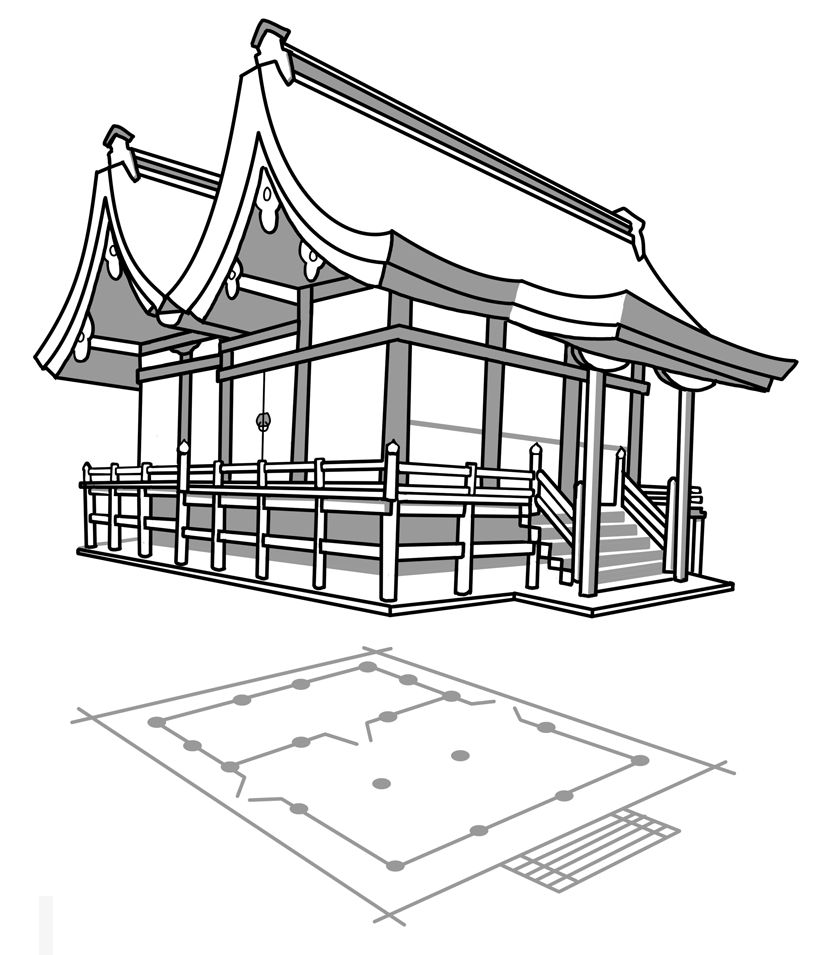

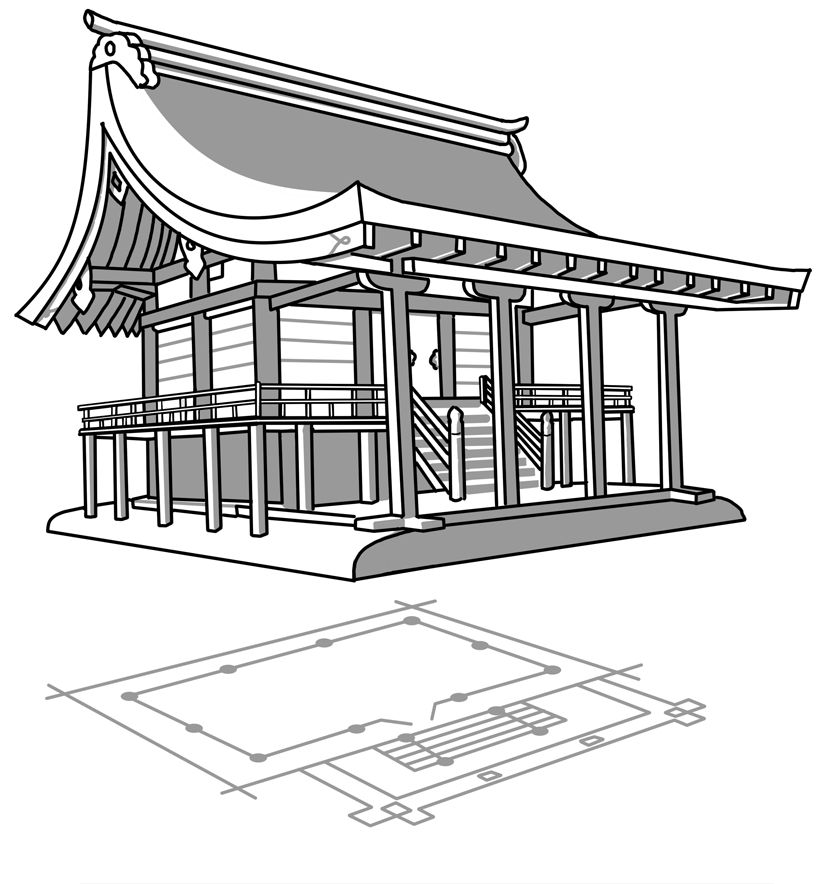

Taisha-zukuri: A type of honden building that probably derived from the house (miya) of the village headman, who was responsible for performing rites for the kami. Nagare-zukuri: This is probably the most common style of honden construction, found all around the country. The name means “flowing style,” and it is characterized by an asymmetric, upward-curving, gabled roof. The “flowing” roofline gives the style its name. The entrance is always in the center of the non-gabled side, and the roof there extends well past the wall to cover the veranda. It creates a full-width portico, sometimes with additional square pillars going from ground level up to the extended roof to support it along the eave (especially where the center section has been further extended to cover the stairs). A veranda wraps around three sides. A variation called ryonagare-zukuri has an extended roof on both front and back sides.

Nagare-zukuri: This is probably the most common style of honden construction, found all around the country. The name means “flowing style,” and it is characterized by an asymmetric, upward-curving, gabled roof. The “flowing” roofline gives the style its name. The entrance is always in the center of the non-gabled side, and the roof there extends well past the wall to cover the veranda. It creates a full-width portico, sometimes with additional square pillars going from ground level up to the extended roof to support it along the eave (especially where the center section has been further extended to cover the stairs). A veranda wraps around three sides. A variation called ryonagare-zukuri has an extended roof on both front and back sides.