Green Shinto is delighted to carry this interview with a Pagan-Shinto believer, Matt Jones, who is a fantasy artist and a follower of Inari. It illustrates the attractions of Inari worship for Western Pagan followers.

*********************************************************************

1) How did you come to an interest in Shinto?

Illustration of a fox familiar by Matt Jones

Ever since I was 14, I have been fascinated with Japan. I found out about the culture and folklore through manga and anime, and researched it extensively. I did my A level art project on Japanese culture, and so found out about Shinto. I didn’t practice it at this time, I was just very interested in it. I had also read that it was impossible for a Westerner to practice Shinto and so this initially put me off.

However, Shinto continued to inspire and influence me and I found some friends online in America who had a kamidana (house altar) to Inari in their home, and so this re-kindled the flame, so to speak. At this time I was a Pagan, though unsure of my path.

At the age of 20 I became involved in the Shinto faith, and bought my first pair of Inari fox statues and set up a shrine in my bedroom. Since then, my kamidana has grown, as has my passion for the Shinto faith.

2) Why did you form a particular attachment to Inari?

I have always been obsessed with foxes. I started drawing around the age of two, and it was then when I basically announced foxes as my favourite animal and drew as many of them as I could possibly draw! Paper, toilet paper, walls – foxes all over!

I remember meeting a red fox at a farm around the age of 10 – it was a wonderful experience to see such a gorgeous animal in the flesh – despite the fact it was in a cage. Later, at 14, I volunteered at a wildlife rescue and was able to have a hands-on experience with a fox – a fox who had been abandoned as a cub. I got to pet him, feed him and walk him like a dog. I felt immediately a strong connection to foxes once again.

Artwork logo by Matt

I then inevitably found the Japanese fox – kitsune – in anime and manga, and I became obsessed with them also. There was a strange kind of nostalgia about the whole thing – like a calling. But I couldn’t understand it. It felt like too big of a thing for me to even comprehend.

When I was 20, I had my own room in a student house and was able to express myself more as an individual. I read many internet articles about the kami Inari, and felt something stirring inside. I can’t explain it. It was almost like I was re-learning something.

When I finally got some fox statues from Japan, I set them up in my room, just the two statues and a tealight candle. I prayed to Inari for protection as it was a difficult time. It felt that a guardian had entered my room.

The few years that followed, I didn’t really involve myself that much in Shinto. I kept getting told that it was silly to worship a Japanese deity, that Shinto was not for Westerners and other such statements. No matter what other deity I tried to follow, I always fell back at Inari’s side. Her influence (and I generally see her as female or androgynous – though she has also appeared as an old man) grew over the years and she appeared in mediation, dreams and through signs in my life.

Long story short, Inari came back into my life with a bang in 2011. I was having a particularly hard time, and she comforted me and guided me into where I am now. I was so grateful to her I decided to become a devotee and do everything in my power to worship her the ‘proper’ way.

Foxes show themselves to me constantly as a reminder of her presence – even my business is named ‘Fox Trail’ as a nod to the torii path of Inariyama [the Fushimi Inari shrine in Kyoto]. Inari coming into my life and taking me under her wing is the best thing that ever happened to me – I feel this is my life purpose.

3) How do you carry out your practice?

The Inari kamidana kept by Matt Jones

I have a kamidana to Inari-sama in my living room where I pray and make offerings every day. Each morning upon waking, I shower and then wash my face, mouth and hands. I stand before the kamidana and perform a ritual – I do the usual bowing and clapping before reciting a norito (in Japanese, and then English – to imprint its meaning into my mind).

I then make an offering of rice, water, salt and any silver coins. Also Inari often receives fresh hot tea, alcohol, fruits and cakes when I present them to her. As I also follow the year’s sabbats, I make generous offerings to Inari on these and often feast in her name. I also follow the Japanese holidays – both those specifically for Inari and others; as well as the full moon.

Leftover meat offerings are taken to the fields nearby, where the local foxes take them. Usually the silver coins go towards things for the kamidana, but right now I am also donating to a charity in England that saves and rehabilitates urban foxes. Inari let me know that I should do this via a dream, and so that’s what’s happening right now.

4) What are the difficulties for a solitary practitioner?

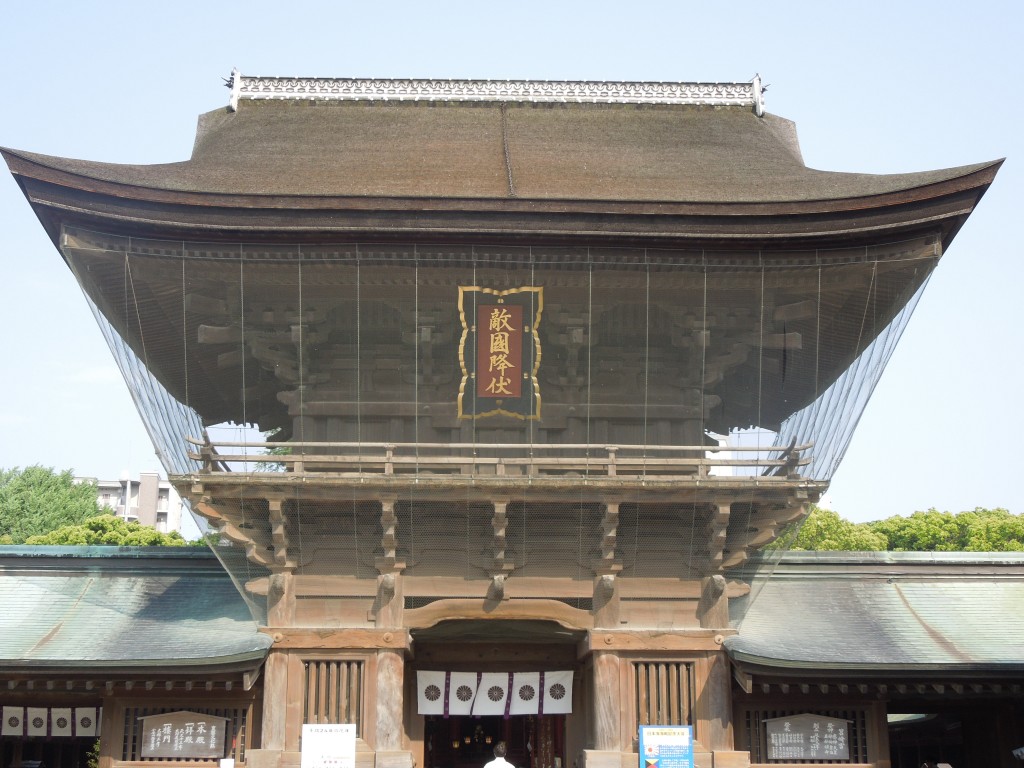

Compared with Japan, Inari worship in the West can be a lonely affair

Personally, the main difficulty for me is the lack of a public shrine of sorts. I aim to make a pilgrimage to Fushimi Inari in a few years, but there is a bittersweet feeling about being in a country that does not have a single Shinto shrine, never mind one to Inari.

Another difficulty being a single practitioner is obtaining the correct types of items for the kamidana, the expenses of importing everything from Japan and also the lack of Japanese markets around – no inarizushi for Inari!

There’s also absolutely no community of followers of Shinto in my area, which makes being a follower pretty lonely. Happily, my fiancé recognizes Inari as our household’s protective kami, and is always interested in learning more about Shinto and Inari.

5) What do others think about your practice and belief?

Many people are very interested in my faith, and are in awe at my kamidana and love for Inari. My family do not understand any specific beliefs involved in Shinto, but they know that it has made me a stronger and better person – and so understand that it’s a very positive thing!

I have friends who want to learn more about Shinto, but find the seeming lack of UK presence for the faith a turn-off. I get lots of people asking about Shinto and Inari, and it would be wonderful if more people were interested!

6) How do you see things going in future – both for you and for the internationalisation of Shinto?

Fox water spout at Fushimi Inari - will the shrine's influence be flowing now into the West?

I am confident that the world needs Shinto right now. The same as it needs other faiths, especially New Age Paganism and Buddhism. I think that there is a lot of positivity in the fact there are various shrines in North America, as it shows that Shinto is NOT restricted to just Japan – and that the practices can be altered for Westerners.

The fact that Fushimi Inari were happy to present a white, American male with a wakemitama of Inari last year is fantastic [see here]. I feel that Shinto is becoming more known worldwide, and the Japanese are perhaps becoming more open to foreigners practicing their faith. As long as we shake off the negative associations with the old State Shinto, and focus on it as a nature religion, I feel that Shinto has a very positive future.

As for me, I aim to help bring Shinto to the West further – my goal in life is to help the establishment of a UK Shinto shrine, and certainly to bring a wakemitama of Inari over here. I feel Inari is guiding me on this journey, and I see nothing negative for Shinto in the future.

———

Websites by Matt Jones:

http://thefoxdruid.wordpress.com/ – A Shinto/Pagan blog

http://www.inarishrine.com/ – Inari resource and information page, which is going to be an online shrine

http://www.foxmoon.co.uk/ – Artwork

But the laws of nature are far stronger than those of mankind. Man must awake at last, and learn to understand how little time there remains before he will become the cause of his own downfall. And he has so much to learn. To learn to see with the heart. He must learn to respect Mother Earth – she who has given life to everything; to our brothers and sisters, the animals and plants, to the rivers, the lakes, the oceans and the winds.

But the laws of nature are far stronger than those of mankind. Man must awake at last, and learn to understand how little time there remains before he will become the cause of his own downfall. And he has so much to learn. To learn to see with the heart. He must learn to respect Mother Earth – she who has given life to everything; to our brothers and sisters, the animals and plants, to the rivers, the lakes, the oceans and the winds.

I knew about the ‘household altars’, or butsudan, which are still seen in most homes and on which the memorial tablets of dead ancestors – the ihai – are displayed. The butsudan are black cabinets of lacquer and gilt, with openwork carvings of lions and birds; the ihai are upright tablets of black polished wood, vertically inscribed in gold. Offerings of flowers, incense, rice, fruit and drinks are placed before them; at the summer Festival of the Dead, families light candles and lanterns to welcome home the ancestral spirits.

I knew about the ‘household altars’, or butsudan, which are still seen in most homes and on which the memorial tablets of dead ancestors – the ihai – are displayed. The butsudan are black cabinets of lacquer and gilt, with openwork carvings of lions and birds; the ihai are upright tablets of black polished wood, vertically inscribed in gold. Offerings of flowers, incense, rice, fruit and drinks are placed before them; at the summer Festival of the Dead, families light candles and lanterns to welcome home the ancestral spirits.