Naturalist Kevin Short’s latest piece for the Japan News concerns the irrigation ponds which are often presided over by a Benten shrine, since the deity is associated with water. (For the full article, see here.)

******************************************************

Kevin Short, for the Japan News

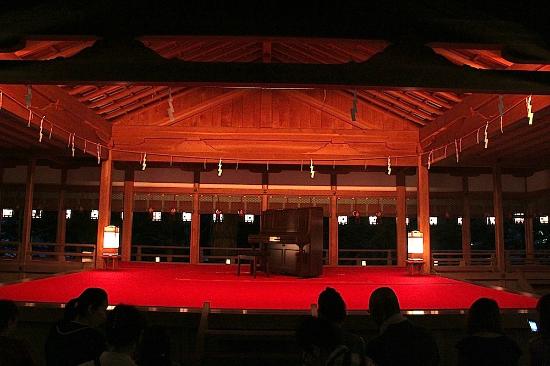

Benzaiten started off as Sarasvati, an Indian native river goddess, but was absorbed into the Buddhist pantheon as a protector deity. Here in Japan she is considered to be the patron saint of musicians and performers, as well as a bringer of fortune. Benzaiten is one of the Shichifukujin, or Seven Lucky Gods, honored at pilgrimages around the New Year.

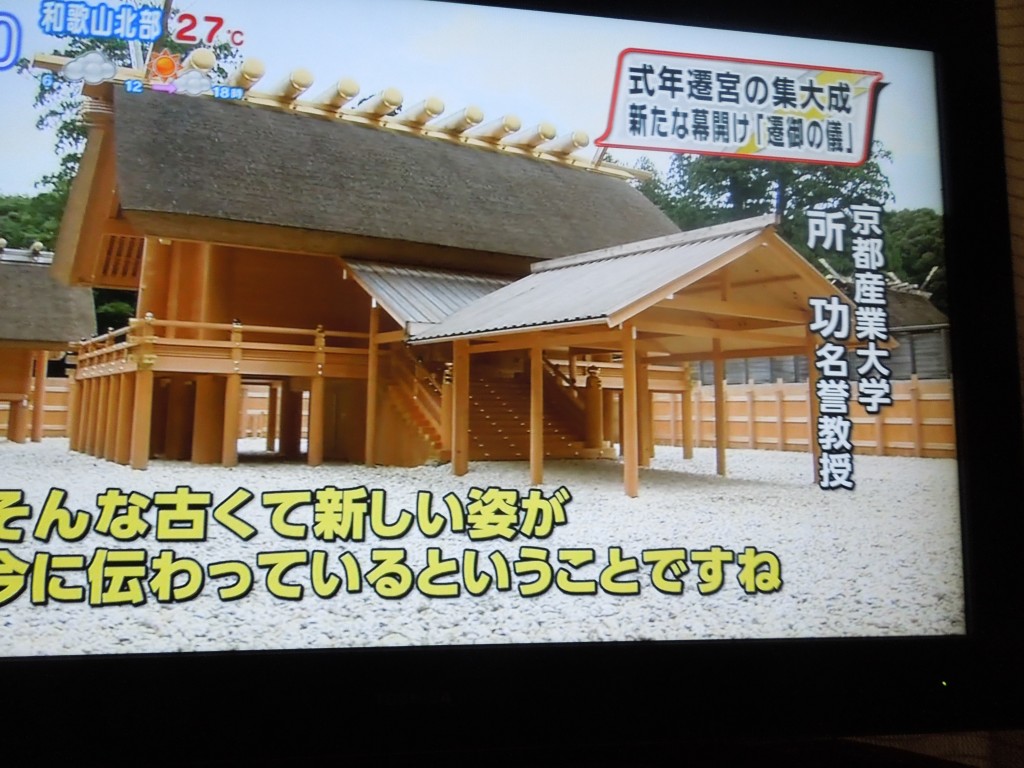

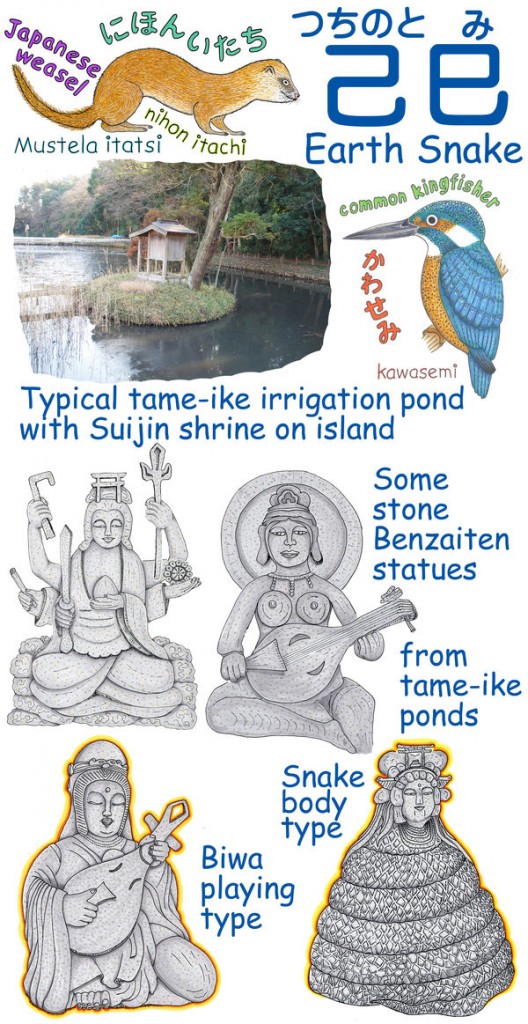

In the countryside, however, Benzaiten is worshipped almost exclusively as a Suijin, or no-nonsense water deity. Most shrines dedicated to her are located on tiny islands set in tameike irrigation ponds.

These simple ponds are typically constructed at the head of narrow valleys, where water seeps out naturally from the surrounding slopes. The water is temporarily collected in the ponds, then sent downstream to the paddies through a system of sluices and ditches.

Interestingly, although Benzaiten is of Buddhist origin, in the countryside she is often worshipped as a Shinto kami. Buddhism arrived in Japan in the fifth century. At first there was conflict between this new religion and the older Shinto-like beliefs. Eventually, however, accommodations were reached.

One way of reconciling the two traditions was to match up Buddhist deities with specific Shinto counterparts. Benzaiten was coupled with Ichikishima Hime, a Shinto suijin worshipped at the Munakata Taisha in Fukuoka Prefecture and the famous Itsukushima Shrine on Miyajima island in the Seto Inland Sea.

In Japanese folk spirituality, however, the distinctions between Shinto and Buddhism have always been blurred at best. For rice farmers a steady, reliable supply of water is absolutely vital, and no one really cares what religious tradition the spiritual energies that protects and animates the irrigation ponds belong to. The tameike ponds are thus major hubs in both the physical and spiritual landscapes.

The tameike also play an important role in preserving local biodiversity and ecosystems. Often fringed with reeds, cattails and other native water grasses, the ponds provide excellent breeding habitat for small fishes, crustaceans, frogs, turtles, and aquatic insects such as dragonflies. Japanese weasels, kingfishers, and several species of egret and heron hunt regularly in the tameike.

Snakes, excellent swimmers that prey heavily on frogs, also abound in the suijin ponds. In fact, in Japanese folk spirituality snakes are considered to be the familiar or spirit-helper of Benzaiten. The goddess is typically depicted playing the traditional three-stringed biwa, but in some spectacular avatars she appears as a coiled snake with a woman’s head.

In many areas water for the rice paddies is now pumped up from underground, and the tameike no longer function as irrigation ponds. The farmers, however, continue to think of themselves as beneficiaries of a natural cosmos. Simple feelings of gratitude for these benefits still runs deep in Japanese folk spirituality, and the tameike ponds and small Benzaiten shrines are usually maintained in excellent condition.

As the countryside landscape modernizes and urbanizes, these ponds become more and more important as bio-reserves, often providing the only local habitat for regionally endangered species. Certain species of dragonfly rely heavily on tameike, as does the Japanese fire-bellied newt.

***************************************

Short is a naturalist and cultural anthropology professor at Tokyo University of Information Sciences.

The Benten Pond at Kyoto's Daigo-ji - not a 'tameike' irrigation pond but a beautifully landscaped temple pond

Indeed since the emergence of the Judeo-Christian tradition, awe is the mandatory reaction that the true believer is required to have towards God. From this perspective the sense awe and wonder is bounded and regulated through the medium of religious doctrine. In contrast, those of us who believe that it was not God but humans who are the real creators are unlikely to stand in awe of this allegedly omnipotent figure.

Indeed since the emergence of the Judeo-Christian tradition, awe is the mandatory reaction that the true believer is required to have towards God. From this perspective the sense awe and wonder is bounded and regulated through the medium of religious doctrine. In contrast, those of us who believe that it was not God but humans who are the real creators are unlikely to stand in awe of this allegedly omnipotent figure. We all have the capacity and the spiritual resources to experience the mysteries of life and the unexpected events that excite our imagination through a sense of wonder. Those who stand in awe of God internalise their sense of wonder through the medium of their religious doctrine. Their response can possess powerful and intense emotions. But the way they wonder is bounded by their religious beliefs and their conception of God. In a sense this experience of spiritual sensibility is both guided and ultimately dictated by doctrine and belief. Historically those religious people who dared to go beyond these limits risked being denounced as heretical mystics.

We all have the capacity and the spiritual resources to experience the mysteries of life and the unexpected events that excite our imagination through a sense of wonder. Those who stand in awe of God internalise their sense of wonder through the medium of their religious doctrine. Their response can possess powerful and intense emotions. But the way they wonder is bounded by their religious beliefs and their conception of God. In a sense this experience of spiritual sensibility is both guided and ultimately dictated by doctrine and belief. Historically those religious people who dared to go beyond these limits risked being denounced as heretical mystics.