This is the second part of a personal account by Quin Arbeitman, an American based in Fukuoka, of how he came to be a Shinto believer. (For Part One, please click here.)

***********************************************************************************************

Shinto Awakenings 2: Geronimo!

The whole prayer thing was brand new to me. I was not raised in a religious household, and though I’d been to church and synagogue a little bit via each of my respective parents’ families, I really was a rank beginner at it.

One of the first websites I read was very helpful to me in that it not only gave the standard rote instructions; more importantly, it relayed a priest’s advice that it really doesn’t matter too much whether you get the rituals right as long as you go into it with a pure intent. And in fact I did mess up the order on just about everything for a while. Clap first? Bow first? Aw, crud. But by approaching it knowing that heart mattered more than form, soon enough the form got better.

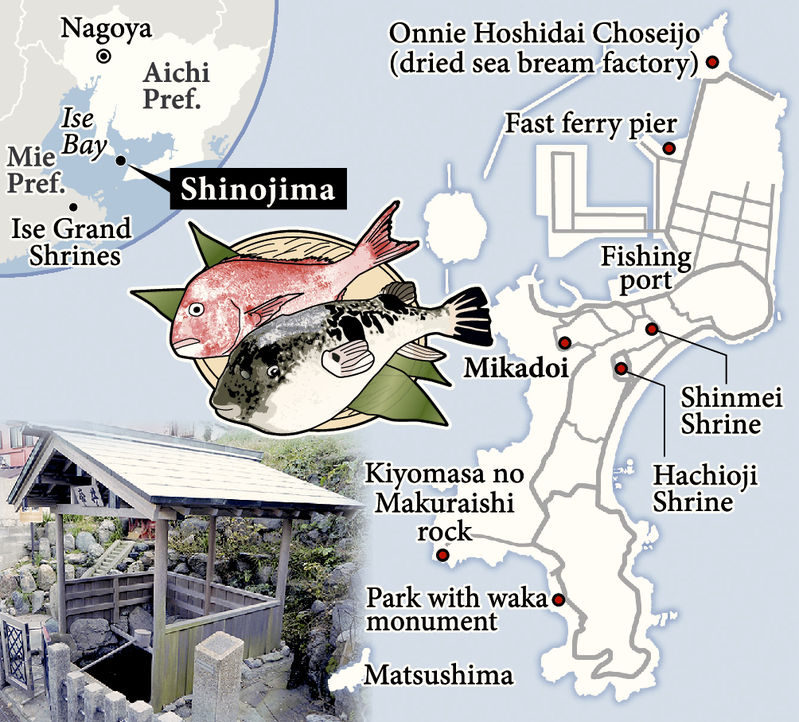

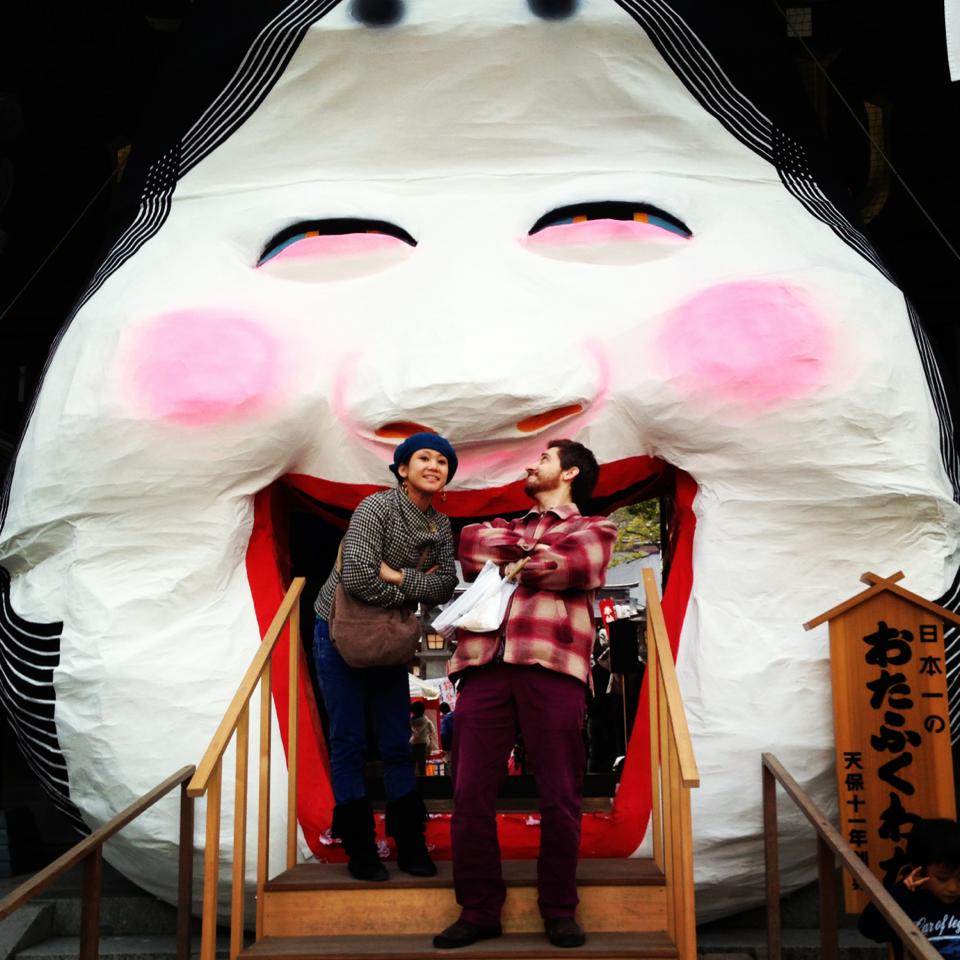

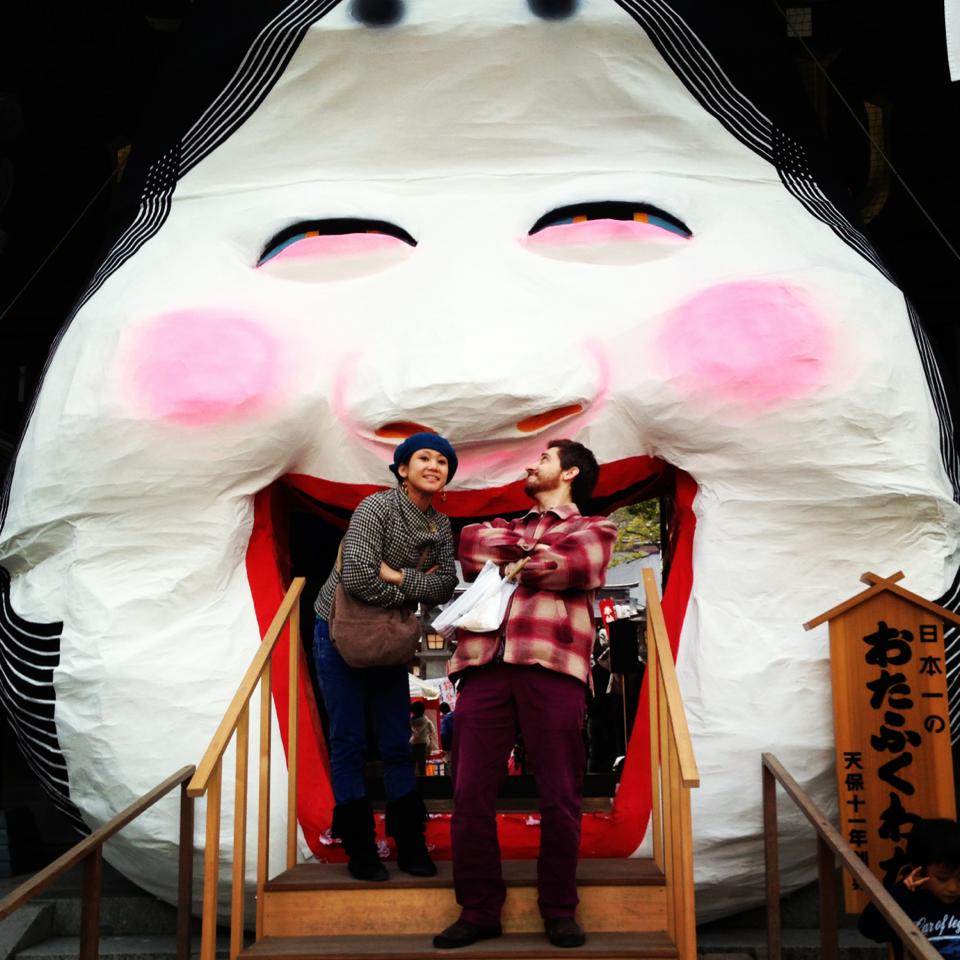

At Kushida Jinja during Setsubun, one passes through Otafuku's mouth in order to receive blessings for the next year. (All photos courtesy Arbeitman)

And I felt fast rewards because of this. Honestly, I found the very act of prayer to be quite pleasant for its own sake. So I kept on doing it. Soon I was stopping by the shrine every day. I discovered an even tinier but equally charming shrine on the route home from my job, and started praying there as well. The only person I told about it was my then-girlfriend, who thought I must be going through a midlife crisis, which I guess is one way of looking at it.

Within a week or two, it was last year’s Setsubun. I went with my girlfriend to the festivities at nearby Kushida Shrine, and happened to arrive just as the big public ceremony for the day was starting. Local celebrities were tossing mochi [rice cakes] and other treats into a dangerously packed crowd, and we found ourselves stuck in the middle of it. People on all sides jumped and strained in vain for the good luck gifts; meanwhile, I just stood there, and somehow, these treats kept on falling on me — catching in the folds of my jacket, no less. A good portent, I thought.

In the midst of this, I was assigned by my English school to travel a few Saturdays to Hiroshima to help train a new teacher there. I visited Gokoku Shrine in the middle of the city, a shrine that was dedicated to the dead of one war in the 1860s, and later rebuilt after it was destroyed by the atomic blast of an entirely different war. I prayed in respect for the war dead, and left in an oddly serene state of altered consciousness. I felt like I was buzzing as I walked, but it was an easy buzz.

As I walked out of the front torii of the park, an imposingly large black van (really in this case, a black bus) festooned with Rising Suns and loudspeakers drove past me, slowing as the driver noticed me. Normally this would cause a moment of fear and unease in my gaijin heart, but in this case, I merely thought, My brother! as he passed. Clearly I was stoned, basically, though not from the usual means. In that moment I just naturally felt a communion with the deep love he also had for his country. This prayer thing packs a punch sometimes, doesn’t it, I thought.

From Quin's first visit to Itsukushima Jinja, February 2013.

On my last day in Hiroshima, I had lunch with the new teacher I was helping to train. We got along swimmingly, and somehow or other the subject of Shinto came up and she mentioned that, by chance, she and her husband were among the less than two hundred people who live full time on the island of Miyajima. That’s the home of Itsukushima Shrine, quite possibly the most famous shrine in Japan, although my knowledge of Shinto was still so minimal at this point that I didn’t even know that the famous picture of the torii gates in the middle of the water that you always see in postcards was in Hiroshima at all. The whole island is considered holy. There’s constrictions placed on how one can go about life there; famously, nobody is supposed to be born there, or die there, in order to keep the purity. I think this partly goes to explain why so few people actually live there. And when I went for the first time, it was as an invited guest of a (western, non-Shinto) resident of the island, one whose house was only a few hundred meters from the shrine. It was as though Shinto was inviting me over for a coffee. What a nice coincidence, I thought.

Then a week later — less than a month into my Shinto dalliance — everything changed.

I had a full-on religious revelation. Visions, out of body experiences, visitations, mysterious symbols, celestial events. All of the bells and whistles one could ask for.

It was not the kind of thing that I really thought could happen to me in real life. Afterwards it was impossible to consider myself agnostic (let alone atheist) any longer. For some reason, I hadn’t gone into this seriously expecting to be able to receive any of the personal gnosis I’d been looking for. Be careful when you wish for life-changing confirmation of deity, you might just get it.

The torii gate at Kego Jinja at sunset. In the lore of many traditions around the world, mystical experience is said to be more common at the in-between areas: at bridges, gates and crossroads; sunrise, sunset, and the times between awake and asleep.

I wasn’t planning to share any of the details here in public. It’s the kind of thing that the more I share, the less I’m apt to be taken seriously by anyone who has not experienced such things themselves. (I certainly didn’t take others’ experiences seriously back when I was an atheist.) But I’ve been thinking about it. Simply by coming out and saying I had such an experience, it’s already too late. Shikata ga nai, ne. I might as well just be as honest and forthright as I can.

The experience came in three parts.

When the first part occured, I was lying in bed attempting to sleep. “Just a dream, then,” the more skeptical among you are already thinking. Having experienced it myself though, I have to say that the quality of my sensations were unlike any dream I’ve ever had. I have no doubt that my being on the boundary between conscious and unconscious is part of what opened the door to this other way of perceiving. Still, call it what you will, but “dream” is not the right way to speak of it.

Two impossibly bright sparkling balls of light approached me from a distance. I really mean sparkling, in that they were very much like multicolored fireworks sparklers, floating through inner space toward me. How close or far was impossible to tell. They seemed to be both impossibly vast and as small as, well, a sparkler; they seemed both a part of my physical reality, and not. If this description is hard to understand, that’s a function of the rather inexpressible nature of this kind of experience.

One of them came up to me and touched me somewhere inside, and my awareness hopped out of my body. It was definitely an Out-Of-Body Experience of the classic sort — I had awareness of being out just a few feet over my body, and my awareness extended out a few feet further than normal to include all of the objects in the room around me, and of course these two floating sparkling light shows before me. Then they departed, and I really didn’t know what to do, except think “Did this really just happen?” and let myself drift to sleep.

In the second part of the experience, I had a dream where I entertained two beautiful women who came to visit. Unlike the visit from the balls of light, this did maintain the general feeling and atmosphere of a dream state. However, what actually happened in the dream was completely unique and not something I’d experienced before, and quite special for me. I won’t be sharing more, though, as I feel that the things the ladies presented me aren’t for me to share in public.

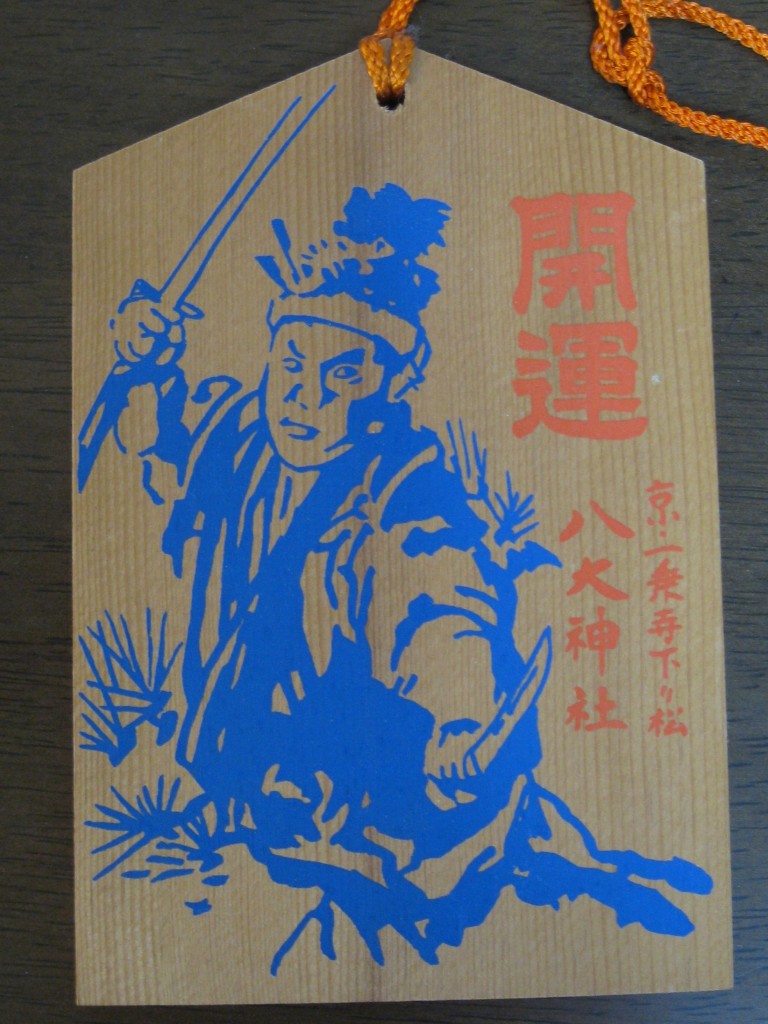

Shitateru Hime Jinja. According to the officials at its head shrine Sumiyoshi Jinja, this tiny shrine to Shitateru Hime is thought to be the sole extant shrine devoted purely to her in all of Japan; a bit surprising, given her mythological importance as the first heavenly poet.

Now, when I started out praying at my two shrines, I just kind of implicitly assumed that the kami I was directing my prayers to were male. (Yes, sexism. I have no excuse.) Needless to say, after this experience, I was more than a little bit curious as to just who exactly I’d been praying to this whole time. It’s a little bit embarrassing that I didn’t already know, actually, but what can I say; I’d still been thinking of myself as simply a dabbling spiritual tourist. So as soon as I could, I went to my local shrines, took pictures of the placards, broke out the kanji dictionary. It turned out that this whole time I’d been praying to Toyotama Hime no Mikoto (“Princess Bountiful Jewel”) and Shitateru Hime no Mikoto (“Princess Light That Comes From Underneath”): two goddesses, both invariably depicted as beautiful women.

Back to the experience, though, as there’s still more. The third part of the experience came the next morning, as I was drifting awake. I was not fully conscious yet, and I suppose what I saw here was also probably a dream. But it was also unique — in this case I was not dreaming of a place or people or anything at all. I was dreaming in abstract symbols, symbols that I remembered and wrote down as soon as I awoke. One I felt represented a god, and the other seemed to represent the number two, although it wasn’t in fact a number two. This section was probably the most mysterious part of the experience and I still haven’t really worked out what it meant.

I wrote down all of my experiences from the previous night as fast as I could, as it seemed important. Then I got up and went to work.

There was, in a way, a fourth part to the experience, although it didn’t occur while I was in any kind of obviously mystical state like the other three. When I got to work, the other teacher on duty asked me if I’d heard the news — a meteor had hit Russia. I googled it, and was astonished. I hadn’t heard anything about this.

On February 15, 2013 — that’s the same time as I was having my experience — not only were the eyes of the entire scientific community watching the skies as near-earth asteroid Duende (Duende is Spanish for “sprite” or “fairy”) made the closest-ever pass to Earth of an asteroid of its size on record; meanwhile, the whole scientific community got sucker-punched by an entirely different and completely unexpected near-earth asteroid, which swooped in from a totally unrelated orbit and exploded over a place called Chelyabinsk Oblast.

That magnitude of meteor explosion only happens about once a decade; when over land in a place where people notice, only roughly once every forty years. For these two events to happen on the same exact day is a coincidence of literally astronomic proportions; for it to happen on the same exact day as my religious experience, which involved two balls of light, two women, and a symbol for the number 2… Well. You can probably guess what kinds of conclusions I drew.

Please do feel free to declare it to be mere coincidence, I don’t mind. My more skeptical friends already have. As I said before, I’m not trying to convert anyone here. I know what happened to me; I am also comfortable knowing that the experience was timed as it was to convince me, and me alone. That’s exactly what personal gnosis is: I’m the only one it can convince.

(By the way, lest you think I am an egomaniac, I don’t believe that the asteroids were a personal message to me or anything. But I don’t believe the timing of my vision was coincidence, either.)

Starting to really believe in invisible, powerful, hopefully benevolent deities is all well and good, but the proof of the okonomiyaki [Japanese omelette] is in the eating, as they say. Has my life meaningfully changed since I finally learned to give up worrying and love the kami?

I’m happy to say that it has.

************************************************************************

For more about Shitateru Hime, mythological Japan’s first poet, click here.

***********************************************************************