Green Shinto is a forum for a wide range of aspects related to Shinto, which include the fundamental values of Japanese culture as well as matters of faith.

Over the past couple of years we’ve been fortunate to carry interviews with some of the leading foreigners involved in Shinto and learnt of what brought them to the religion. (See here, here or here.) Now Green Shinto takes special pleasure in announcing the first part of a personal journey by a young Westerner in Japan for whom Shinto has provided a spiritual focus.

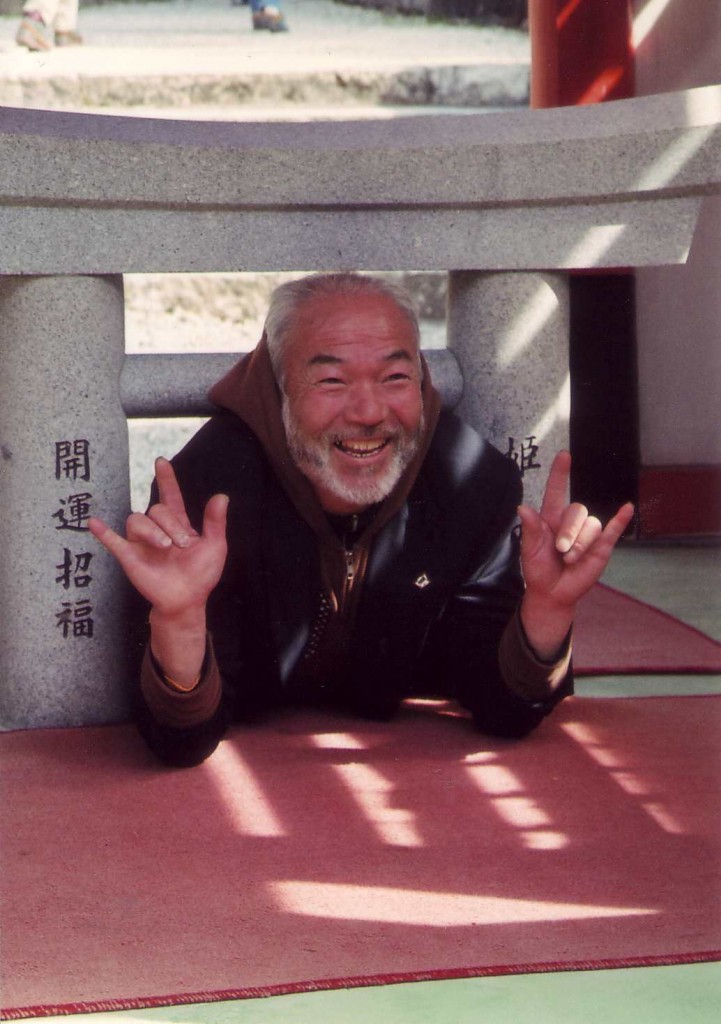

Quin Arbeitman is based in Fukuoka, and hails from New York State. He’s lived in Japan for 9 years, and is an English teacher and jazz pianist. The selfie on the left shows him at the Hakozaki Tamaseseri festival, when half-naked men scramble for a ball while being showered with cold water. There’s an interview about the musical side of his life here, and to listen to some samples of his superb swing style click here.

****************************************************************************************************

Shinto Awakenings 1: One Year of Shinto

As I write this, it’s the end of the day on February 3rd, also known in Japan as Setsubun, a holiday probably most famous for the fact that it involves ritual demon exorcism that’s fun for the whole family. So after kicking out all the demons out of my place, I sat down and ate myself 39 roasted soybeans, one for each year of my life. As I ate each one, I tried to remember at least one thing from that year. An interesting exercise, I recommend it highly.

Setsubun: Home alone, Quin played both the part of Otafuku and the Oni, before eating one bean for every year of his life (all photos courtesy Arbeitman)

I have to say that the 38th soybean turned a little bit poignant. As I chewed, I reflected on the fact that it marked the year in which I began to practice Shinto. In fact, by a certain way of reckoning, it’s been exactly a year to the day, as last year’s Setsubun was the very first Shinto event I ever participated in with a mind and heart sincerely open to the possibility of a hidden reality inside this troubled world we share. Over the last twelve months, that single change has opened the floodgates to a whole different universe of experience.

This blog’s proprietor has asked me to write something about my personal experience as a Shinto practitioner. It’s with a little bit of trepidation that I write this. It’s scarier than you might think to come out of the sakaki closet. Unlike many other closets, there’s not much in the way of company out here. Literally the only other foreigners I’ve ever had contact with who self-identify as Shinto practitioners have all gone that extra mile (or thousand miles) and trained to become a full-fledged priest or priestess. And in the Age of the Internet, there’s a very real risk that from here on out, I’ll be forever seen as some kind of kooky religious flake. Strike One with prospective employers and so forth.

Ah well. Mainstream acceptance is overrated anyhow. By going on the record like this, it’s my hope that any Hidden Shintoists hiding in the woodwork will feel free to contact me, whether publicly via the comments on this blog or privately through my website, as it’s a little lonely being the only non-ordained Shintoist foreigner I know. To the rest of you out there, please let me assure you that it really is not my wish to act as any kind of missionary for Shinto, eager to convert the Tall-Nosed masses to the “Way of the Gods”. In fact, it was precisely the fact that Shinto did not preach to me in the slightest which let me feel like it was safe for me to approach in the first place.

So. American. In Japan. English Teacher. Pianist. Atheist until recently. Now not so Hidden Shintoist. How did I end up here, anyway? I’m not entirely sure myself.

I do believe I am probably not alone among the people who read this when I say that over the last several years, a kind of deep rooted existential malaise had been creeping its way into my heart. Really this started a very long time ago – at least as far back as my teens – but it had only gotten worse in recent years. Certainly I generally thought of myself as happy; but it was happiness with a ruling house of insecurity. This was in large part because I had no confidence in there being any satisfying answers to the deeper questions about our place in life, in the universe, in everything.

The problem I was having with atheism — and I recognize this is no argument which refutes it on logical grounds — was that it held no sustenance for me for any of the questions that really mattered. If we do not accept a deeper spiritual connection between all things, if anything we do fades away once we die, and no matter how high we soar or how low we fall our ultimate fate is uncaring oblivion, then why does anything we do matter at all? Why be choose to be good? Why choose to be anything? Who cares, really?

Some atheists answer “Why does anything need to matter? Maybe it just is,” while others answer, “We bring our own meaning to the universe”, and there are certainly atheists that would say other things too. But none of the answers I found there left me on solid ground emotionally or spiritually. Every time I tried to consider humanity’s place in an arbitrary mechanistic universe, I got this kind of overwhelming existential vertigo and eventually did my best not to think about it.

Wakamiya Jinja in Imaizumi, Fukuoka, where Quin first prayed on his own. It enshrines Toyotama Hime no mikoto.

This was not a recipe for spiritual balance. It was like eating a diet of bread made largely of sawdust (or as they prefer to list it on today’s packaging, cellulose): sure, you may feel full after any particular meal, but over time you just end up more and more undernourished.

Of course, I don’t believe that me wishing for the universe to have a deeper meaning can make it so. I just hope to articulate why I was in the mood to explore something different, that’s all. That I actually eventually discovered something deeper, I am grateful for.

Now, one approach I was coming across now and then which appealed to me was that there might be some kinds of religious experience which could only be understood from the inside. Perhaps independent, repeatable, externally verifiable proof might be impossible, but personal gnosis was still something, I heard it claimed, that was quite attainable. I decided to give it a chance, and choose a faith in which to lark about for a while as a kind of “religious tourist” and see how it made me feel. If nothing else, I thought, perhaps the very act of trying might give me a bit of the inner contentment I felt was lacking.

But which religion to choose? For a variety of personal reasons I didn’t really feel comfortable with any of the major religions that I knew from America. And seeing as I lived in Japan, it seemed like it could also be a good opportunity to connect with Japanese culture a little bit as well. Being that Buddhism was far too trendy among foreigners and I like to defy expectations a bit, that left only Shinto. (So if I feel lonely in my choice of faith, I guess I only have myself to blame, don’t I!)

I got on the net and did a little bit of reading. As any regular Green Shinto reader probably knows well, there’s not a great deal about Shinto in English on the internet — although maybe something is changing in the zeitgeist, as it seems like there’s already more right now than when I first started poking around a year ago. (In no small part due to the efforts of this very blog, I should add. This blog has been a godsend for me — perhaps literally.)

At the time I couldn’t make much sense of the dizzying assortment of deities with long names, but the actual practical steps I could take to start to practice seemed straightforward enough. Ablution, left-right-left-gargle-left-ladle. Worship, donate-bow-bow-clap-clap-pray-bow. Simple in theory, anyhow.

I don’t know exactly what day I started — I didn’t take notes, I didn’t say “this is the day I’m going to start praying at Shinto shrines” — I just did the necessary reading, thought about it for a while, and then one day kind of found myself going inside the shrine nearest to my apartment, and praying.

I was self-conscious, of course, but I approached the task with sincerity. I imagined myself stepping into the spirit world as I passed through the torii gate. I imagined my spirit become purer as I rinsed my hands in the ritual manner. I imagined there to be a real kami there who I was communicating with as I prayed, and introduced myself to them, and expressed the desire to become acquainted. I imagined myself stepping back into regular reality once I passed through the torii gate once more.

To be clear, I don’t think I really believed at that time that any kami were actually there. I just decided to act as though they were for a while, just to see what would happen. I thought of myself as a kind of “religious tourist”. A tourist doesn’t wait until they have a doctorate in Spanish to go to Spain; they certainly don’t try to get Spanish citizenship first. They just pack their bags and go there. Similarly, I started practicing Shinto without really knowing anything about it. I left the theory for later, and just started trying to do things.

I think this was the right approach. I’ll talk about how it went next time.

Dressed to the nines, Quin prior to lifting the palanquin for the Kaguya Hime festival connected with Wakamiya Jinja

But just because something’s sacred doesn’t mean it can’t be used for amusement. One example is shown in the first photo, which is a scene from the Flower Festival at the Awashima shrine in Unzen, Nagasaki. (You might remember that Unzen was the location of some severe volcano eruptions in the early 1990s.)

But just because something’s sacred doesn’t mean it can’t be used for amusement. One example is shown in the first photo, which is a scene from the Flower Festival at the Awashima shrine in Unzen, Nagasaki. (You might remember that Unzen was the location of some severe volcano eruptions in the early 1990s.)

The deer in Nara Park are wild animals designated as a protected species. It was said that at the time the Kasuga Grand Shrine, a World Heritage Site, was first built, the god of Kashima Shrine came in a white deer when it was transferred to the new shrine. Since then, they have been revered as messengers of the gods and thus carefully protected.

The deer in Nara Park are wild animals designated as a protected species. It was said that at the time the Kasuga Grand Shrine, a World Heritage Site, was first built, the god of Kashima Shrine came in a white deer when it was transferred to the new shrine. Since then, they have been revered as messengers of the gods and thus carefully protected.