Anapa (better known by the Greek name Anubis) was a jackal-headed god associated with the afterlife.

There are people who like to promote the idea that Shinto is somehow special or ‘unique’. It’s not. It’s part of a community of pagan religions, and a Green Shinto reader named Malaz who is a priest of Sekhmet from the Kemetan faith of ancient Egypt has highlighted the similarities between the two religions.

**********************************************************************************

Malaz comments: In studying the contrast between Kemetan and Shinto belief, I found there are many concepts which are similar. There are more ideals in the two faiths which are alike than not.

An important factor for this study was realizing that, while there are so many ideals that compare, the issue seems to be that the Japanese have more “names for their ideas”. Aidono is an excellent example. It is the Japanese word for the idea that there are subordinate deities in a particular shrine. Of course, the Ancient Egyptians had principal deities and deities to the right and left of altars but with the exception of the title, “HA.w-kAr”, and no way to prove that this title was used in the same way as the word Aidono, we must simply acknowledge that the two faiths practice/d in a similar way, but did/do not necessarily label them in this manner.

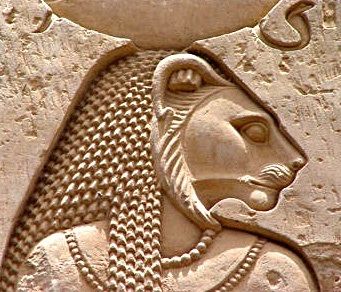

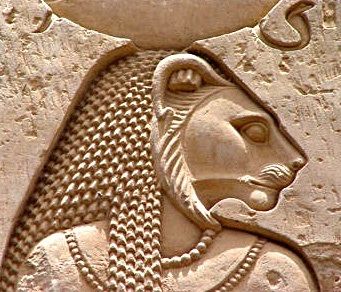

Sekhmet, a solar deity and daughter of Ra, who was also a warrior goddess and depicted as a lioness. (All photos here supplied by the author.)

Amaterasu – primary deity/ sun goddess / warrior / mother goddess

Sekhmet – primary deity/ sun goddess / warrior / mother goddess

Amatsukami, Kunitsukami “Kami of heaven,” “kami of earth.”

sbAy.w star Gods Akr Aker (god); the earth; earth-gods

Aki matsuri: Autumn Festival

Min Hadab: Autumn Festival

Aku: unhappiness, disaster, or inferiority of nature or value

jj.t disaster njd label for something impure, harmful

Araburu kami: Malignant gods who bring affliction to human beings.

wr-nxt “demon” (The Egyptians had many words for deities which could be potentially harmful)

Banshin immigrant deities

The Egyptians adopted a few gods from other cultures, but there was no distinction in vocabulary. Examples of adopted gods are Bes (seen below), Osiris and Neith.

Bokusen Divination.

(The Egyptians had many types of divination)

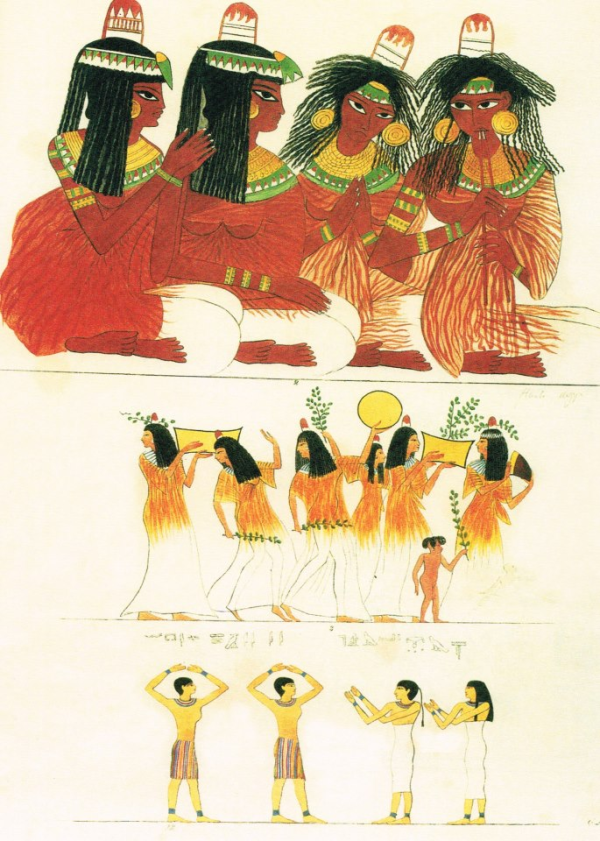

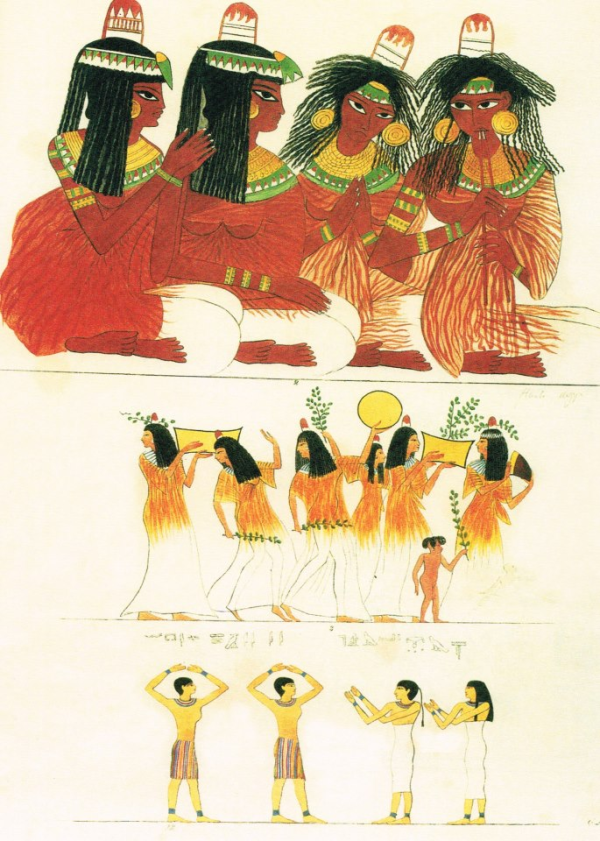

Ritual dance, Egyptian style. Notice the sun-like disk and green plants (like sakaki) being held by dancers in the lower part of the picture.

Bon matsuri A festival celebrated around July or August 15 in order to console the spirits of the dead.

Sokar Hadab One of several festivals for the dead.

Boshijin Mother-child kami

Iwn-mwt.f Pillar-of-his-mother, a name of Horus

Chinju no kami A tutelary god protecting a specific geographical area.

(The Egyptians had a local god for each home)

Chi no wa A circle made of plants for casting off sources of misfortune.

zAr.w “tying up” (See “zar exorcism” in modern Egypt)

Daiguji Supreme priest (the highest priest is considered the emperor himself)

Hm-nTr-tpj high priest (note: the true high priest was considered the Pharaoh himself)

Dashi Festival float

(The Egyptians also used a barque during festivals to carry images of their deities)

Gunshin Ikusa no kami, Ikusa gami tutelary kami of battle,

xA.tjw fighting Gods

Haishi joint tutelaries alongside a shrine’s primary object of worship (shushin or shusaijin)

nTr.wy (Two) the Two Gods

Harae-do A place (do) for the performance of purification (harae)

wab.t Purification Place (In Ancient Egypt (as in modern Japan) the rivers next to shrines were considered the ‘best practice’ purification place, however, there were also “sacred baths” next to many Egyptian temples where priests bathed 5 times a day. nTri (noun) purification nTri (verb) to be divine (Note: ‘Ntr’ denotes both purifying and the purifying gods.)

Purification of the gods in ancient Egypt

Himachi Waiting for the sun. A popular religious custom in which a company of believers assembles at a member’s home on set days, such as the 15th of the first, fifth, and ninth months of the lunar calendar, to hold a religious ceremony, spend the night in fellowship, and worship the rising sun.

(Ancient Egyptians also did similar things. Though popular scholarship claims Ra as Sun god, It is more likely that, given the matriarchal nature of the lineage of the pharaohs, Sekhmet (like Amaterasu) was given highest status.)

Hi matsuri A festival centering around fire.

ax [site of the fire sacrifice]

himegami female-kami

ntrt goddess

Hi no kami God of fire. Fire itself is not worshiped in Japan, but various deities in charge of fire are worshiped.

(The Egyptians had several fire deities including Ammut, the Devourer of Spirits)

Hitorigami A kami which came into being alone.

(The Egyptians had several deities which were considered “self created”. Khnum was one of them.

Kagura A performance of classical ceremonial music and dance.

(The Egyptians also had many types of ritual dance and song)

Ritual barque in ancient Egypt, equivalent of the Shinto mikoshi

Kami An appellation for the objects of worship in Shinto. An honorific term extolling the sacred authority and sublime virtue of spiritual beings.

Dsrt: goddess, spirit, wine (several other things considered “holy”) (While the term “Netjer” ntj.r is commonly used to describe Egyptian Spiritual Beings, the word “Dasarat” seems more fitting as it can also refer to holy objects, places and animals.)

Kamidana Household altar (literally, god-shelf)

Hr.t sacrifice table, altar

Kegare Pollution. Thought originally to have meant an unusual condition. Some scholars interpret it to mean the exhausting of vitality.

njd label for something impure

Kibuku Mourning. It is customary to refrain from leaving home during a certain period of mourning for the deceased.

imw mourning ritual

Magatsuhi no kami Gods who bring about sin, pollution, and disaster,

aAh.w-ib harmful deities

Priests may have carried out similar functions in Ancient Egypt as in Japan, but they sure dressed differrently

Megumi The granting of a blessing. The bestowing of grace. Mi-megumi is the form used when referring respectfully to a blessing from a god, a parent, or a person of superior rank.

Htp-di-nsw boon which the king gives. The term uses the above mentioned “Hdb/Htp” which implies a divine origin of the granted request.

Miko A priestess serving as an assistant at a shrine. Roles of the miko include performing in ceremonial dances (miko-mai) and assisting priests in wedding ceremonies. In ancient times, women who went into trances and conveyed the words of a god were called miko; today, this tradition still lives among the people, independent of the shrines.

h.m-nt_r priestess The Hamat Natar had many different functions but the designation “.t” denotes special terminology for females.

Myōjin An archaic term used to refer to deities of particularly impressive power and virtue

sxm Powerful One skm Power/Powerful (applied to any powerful deity, including the most powerful: Sekhmet)

x-No-kami Gods of whatever…

x-Ntj Gods of whatever…

Shinto practitioners make offerings of votive tablets, food…etc..to their gods at small shrines and large temples

Ditto Egypt

takaikan Other worlds which are the sites of residence for the dead and transcendental entities

(The Egyptians had several “other worlds” but not a single word to describe all of them)

tenson-kōrin the time of the Heavenly Grandson’s descent to Japan (signifying a divine imperial line)

Narmer/Menes the first human ruler of Egypt, directly inheriting the throne from the god Horus. (Each king took a Horus name to signify that his/her rule was of divine origin.)

The symbolic gateways of the temples in ancient Egypt, though made of stone are reminiscent of torii

A selection of ancient Egyptian amulets, reminiscent of Japanese netsuke