This is the penultimate in a series comparing Shinto in Japan and Paganism in Britain. The previous postings considered Shinto of the Edo era (1600-1867), including syncretism and Nativism. Now the focus shifts to the nineteenth-century pagan revival in Britain – apt enough since today is the winter solstice, widely celebrated by the neo-pagan community.

****************************************************************************************

The cult of Greece

Pan, the player of pipes

In early nineteenth-century Britain the populace identified strongly with Christianity, though there were considerable differences between the various churches. The mainstream was represented by Anglicanism, also known as the Church of England, which was officially recognised as the state religion. Non-Conformists and Catholics were marginalised by being excluded from leading institutions. Bishops of the Church of England served in the House of Lords: others were barred. The University of Oxford, which had for long doubled as Anglican seminary and finishing school for the élite, was firmly closed to all non-Anglicans until reforms in the mid-nineteenth century opened up entrance to students of other persuasions (reforms later in the century opened up the teaching staff too).

In public consciousness there was little if any awareness of Paganism, though elements remained from the past in folk customs such as Mayday celebrations or local festivals. During the course of the nineteenth century, however, there was a rise in interest in the religions of the past. This was partly due to doubt in the truths of Christianity as Darwinism, utilitarianism and advances in Bible studies assailed former certainties. It was also partly the legacy of Romanticism, as the intellectuals of the age sought refuge in the past. The first indications of a change in attitudes came in the appeal of Greek and Roman paganism to the likes of Goethe, Shelley, Byron and Keats. In ‘Song of Prosperius’ Shelley wrote:

Sacred goddess, Mother Earth,

Thou from whose immortal bosom|

Gods, and men, and beasts have birth

Leaf and blade, and bud and blossom.

Later in the century the poet-rebel Swinburne was even more bold, declaring Christianity a religion of death while the goddess Venus represented nature, joy and vitality. His tutor at Oxford was Benjamin Jowett, who together with Walter Pater was influential in promoting Greek ideals amongst a generation of intellectuals. One of the most famous was Oscar Wilde, whose writing is infused with reference to classical deities. He even wrote a poem in which the Roman gods who arrive after the conquest of Briton compare the English countryside favourably with their homeland and wish to stay.[1]

The most popular pagan god was the Greek deity Pan, horned and half-animal, identified by poets with nature. The sentiment found fullest expression with Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows (1908), in which the section on ‘The Piper at the Gates of Dawn’ depicts Pan as guardian of the countryside and childhood. A similar feeling was expressed the same year in verse by Eleanor Farjeon, in a collection entitled Pan-Worship and Other Poems (1908):[2]

The Pagan in my blood, the instinct in me

That yearns back to nature-worship, cries

Aloud to thee! I would stoop to kiss those feet,

Sweet white wet feet washed with the earth’s first dews.

The Romantic interest in the realm of the imagination led in Victorian times to a rediscovery of ‘cunning folk’ and gypsies who used herbs, charms and traditional remedies for the prevention of illness. At Oxford Matthew Arnold wrote one of his most famous poems about ‘The Scholar-Gypsy’ who drops out of university to seek a higher truth in nature. The notion of hidden truths found its fullest expression in the influential The Golden Bough (1890) by James Frazer, which identifies the theme of death and rebirth as fundamental to ancient myth and folklore. Ironically the intention was to show the primitive absurdity of such ideas, but as it turned out the book fostered a fascination with ancient customs that was to have a profound influence on writers such as Yeats, Joyce, D.H. Lawrence and Robert Graves (whose White Goddess (1948) was in turn hugely influential).

Magick and the legacy of Romanticism

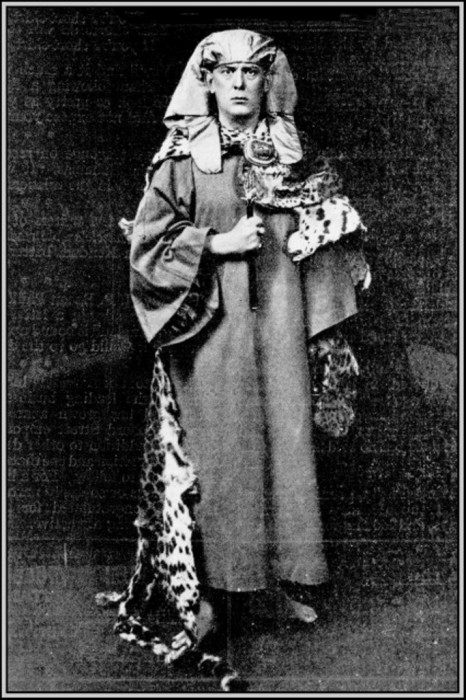

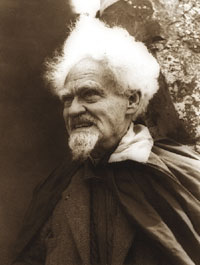

Aleister Crowley in ritual mode

By the early twentieth century Blake’s ‘dark satanic mills’ stood in contrast to an imagined past of rural vitality rooted in worship of Mother Earth. Ron Hutton’s magisterial The Triumph of the Moon (1989) provides a detailed account of the revival of Paganism in these years. The Folk-Lore Society, set up in 1878, promoted in Hutton’s words an ‘imagined paganism’ to do with primal forces – Earth, Sky, Vegetation, Mothering. Added to this were Oriental ideas, evident in such groups as the Theosophical Society, which fostered the notion of balancing masculine and feminine forces.

Amongst the leading lights in the new spirituality was Aleister Crowley (1875-1947), who proclaimed ‘There is no god, but man’ and who pursued an interest in spiritual ‘magic’ (magick). His eclectic practices drew on a wide variety of sources, above all Egypt which he regarded as the origin of esoteric thought. The Ordo Templi Orientis which he founded took its magical tools from the Masons while also borrowing from Freemasonry, the Knights Templar and Tantric traditions. Crowley spoke in mystic terms of rituals that tapped into the wellsprings of existence, thereby creating the allure of hidden powers around his secret practices. As such he was a key figure in the revival of ‘modern witchcraft’, if by that term one means those who practise magick (the ability to affect change by spells and charms).

Crowley’s influence lay behind a publication, which in hindsight has been accorded great significance. Witchcraft Today (1954) was a provocative title, given that witchcraft remained stigmatised (the Witchcraft and Vagrancy Acts had only just been repealed, in 1951). The book was written by Gerald Gardner (1884-1964), a man with an interest in the occult who had grown up in Ceylon and Malaya. In 1936 he retired to the UK, and in his book he wrote of coming across a witch’s coven in the New Forest which practised rites handed down from an ancient pagan tradition. These included dances, consecrated food and drink, and veneration of a goddess as well as a god. Ceremonies were held within a sacred circle formed by a consecrated knife or sword, there were seasonal festivals, and during rituals trance and ecstasy were used to commune with the deities. Most shocking of all, the ceremonies were carried out naked.

Gerald Gardner, discoverer or inventor of Wicca?

In The Triumph of the Moon Hutton supposes that much of this derived from Aleister Crowley, whom Gardner had met in 1947. The younger man was about to become head of Crowley’s Ordo Templi Orientis when he discovered witchcraft, and in his book he borrows elements from both groups. ‘They consisted,’ says Hutton, ‘of a sequence of initiatory rites based on Masonic practice and Crowley, with some novel features, plus a blessing for wine, and a set of ceremonies and declarations of theory drawn from existing published sources.’[3] In this way what purported to be an ancient tradition was in fact a mix of assemblage and innovation. Gardner was well versed in different traditions, and through his experiences abroad he was able to draw on both East and West, including tribal animism, spiritualism, Freemasonry, Co-Masonry, Folk-Lore Society, Ancient Druid Order, Order of Woodcraft, Chivalry, Aleister Crowley and scholarship in such areas as the occult and archaeology. ‘Beneath the label of “the Old Religion” an extraordinarily novel one was taking shape,’ writes Hutton.[4]

Gardner’s unorthodox practice, which came to be called Wicca, spoke to a generation disaffected from orthodox religion. (Wicca derives from an Indo-European root word meaning ‘to bend or shape’.) Part of its appeal was that in contrast to Christianity there was no moralising dogma and no doctrine beyond the simple Wiccan Rede: ‘An it harm none, do what ye will.’ Moreover, in its privileging of the feminine it was in accord with a growing belief that ancient mankind had worshipped a supreme female deity. Robert Graves, for example, in the influential The White Goddess asserted that the entire ancient world had worshipped a triple moon goddess, the inspiration behind true poetry. Wicca thus appealed to the youth movement on ecological, feminist and non-moralising grounds, and it came to form the mainstream of a burgeoning Neo-pagan movement which looked to the religions of the past in such diverse forms as Viking, Celtic, Saxon and Hellenic Reconstructionism.

The Sixties generation

When Gardner’s book came out in the mid-1950s, disaffection with the status quo was beginning to show itself in the form of movements such as that of the CND against the nuclear bomb. In the decade that followed the unrest was to swell into a cultural revolution that represented a paradigm shift in attitudes. Modern commentators, searching for the roots of the 1960s, talk of ‘a long decade’ starting in 1956 when John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger brought the Angry Young Man to the forefront of public consciousness and the Suez crisis showed that Britain no longer ruled the world.

Back to nature became a rallying call for alienated youth in the 1960s

Driven by advances in psychotherapy, young people were more concerned with authenticity than the self-control of the gentleman which had served as model since Victorian times. Repressing one’s emotions was increasingly rejected in favour of freeing oneself of ‘hang-ups’, and ‘Letting it all hang out’ became the slogan of the times.[5] As a result there was a move towards sexual freedom and personal development, which went in tandem with a search for inner truth. Meditation and trance (as in the Hare Krshna movement) helped meet the need. When the Beatles went to India on retreat in 1968, the youth of the Western world went with them. Christianity was left behind.

In its championing of a single male God, the church was widely seen as promoting patriarchy and an unbalanced view of the world. Moreover, in terms of morality, such as its disapproval of extramarital sex, it was held responsible for promoting psychological distress. In the new ‘liberated’ climate, conventional church-going seemed sterile and meaningless. Interest focussed instead on Zen Buddhism, Hindu meditation and Daoism. Along with the East, the New Romantics of the 1960s looked to the past for inspiration, as a result of which Gardner’s Wicca found favour with a whole new generation.

Though it was once assumed that Wicca Paganism, and the wider neo-Pagan movement, represented a revival of ancient ways, it’s recognised now that this was not the case. (Neo-paganism is used as an umbrella term to denote various groups which seek to revive the religions of the past while adjusting them to the needs of the present.) The practices are seen rather as having been consciously formed to reflect what was imagined to be the ancient ways. In this respect Wicca can be considered to be an ‘invented tradition’ which gives the illusion of continuation.

The Pagan Federation in Britain, largely run by Wicca practitioners, has been the fastest growing religion in the UK in recent years. Since it includes all kinds of ‘reconstructed’ ancient religions, from Greek gods to Scandinavian deities, it has had to adopt the broadest of guiding principles, namely: 1) inherent divinity of the world; 2) freedom from dogma; 3) male and female divinities. Hutton’s comment on these principles is instructive: ‘At a glance it should be obvious that these principles can also characterise not only every other variety of modern Paganism [in addition to Wicca], but some varieties of Hindu and Shinto beliefs and many tribal religious systems.’[6]

It seems then that the long British track to neo-Paganism had ended up with something akin to Shinto. It’s no wonder then that many neo-Pagans look with interest to the Japanese tradition.

[1] See Oscar Wilde ‘The Burden of Itys’ in Complete Works Collins, 1948

[2] Quoted by Ron Hutton on p.48 of The Triumph of the Moon: A History of Modern Pagan Witchcraft Oxford paperbacks, 1995

[3] Ron Hutton The Triumph of the Moon p.232

[4] ibid, p.236

[5] See John Dougill ‘The Rise and Fall of the English Gentleman’ Ryukoku Daigaku Ryukoku Gakkai No. 454, 1999

[6] Ron Hutton The Triumph of the Moon p. 390