Green Shinto is delighted to have a firsthand report of the recent climax to the 20 year cycle of renewal at Japan’s premier Shinto shrine, Ise Jingu. It’s a rare and special privilege to be able to attend this most sacred of rites, and this account comes to us courtesy of Peter Grilli, president of the Japan Society of Boston. Many thanks to him!

********************************************************************************************************************************************

“The Silence of the Sengu: Reflections on Time at the Grand Shrines of Ise” By Peter Grilli

Every twenty years, the Imperial Grand Shrines at Ise are totally rebuilt in a process known as the “Shikinen Sengu” that extends back in time to the eighth century or earlier. Though the origins of this cyclical custom may be shrouded in mythology, the faithful adherence to the principles of the Shikinen Sengu has resulted in the preservation of ancient Japanese architectural and ritual forms until the present day. As the ancestral shrines of the emperors of Japan, the shrines at Ise are the most sacred sanctuaries of Shinto and their design and physical form are considered the purest expression of Japanese aesthetic ideals. Dedicated to the Sun Goddess and the God of Agriculture, the shrine buildings house symbols of the deities’ spiritual presence. Occurring only once every twenty years, the transferal of these sacred objects from the old shrine into the new one that has been constructed on an adjoining site is the single most important ritual of the Shinto faith. The 62nd Sengu in Japanese history took place at Ise in early October, first at the Inner Shrine (Naiku) on the evening of October 2 and three days later at the Outer Shrine (Geku). Peter Grilli, President of the Japan Society of Boston, was invited to attend the ceremony at the Inner Shrine, and recorded these observations.

Steps leading to the Naiku inner shrine at Ise

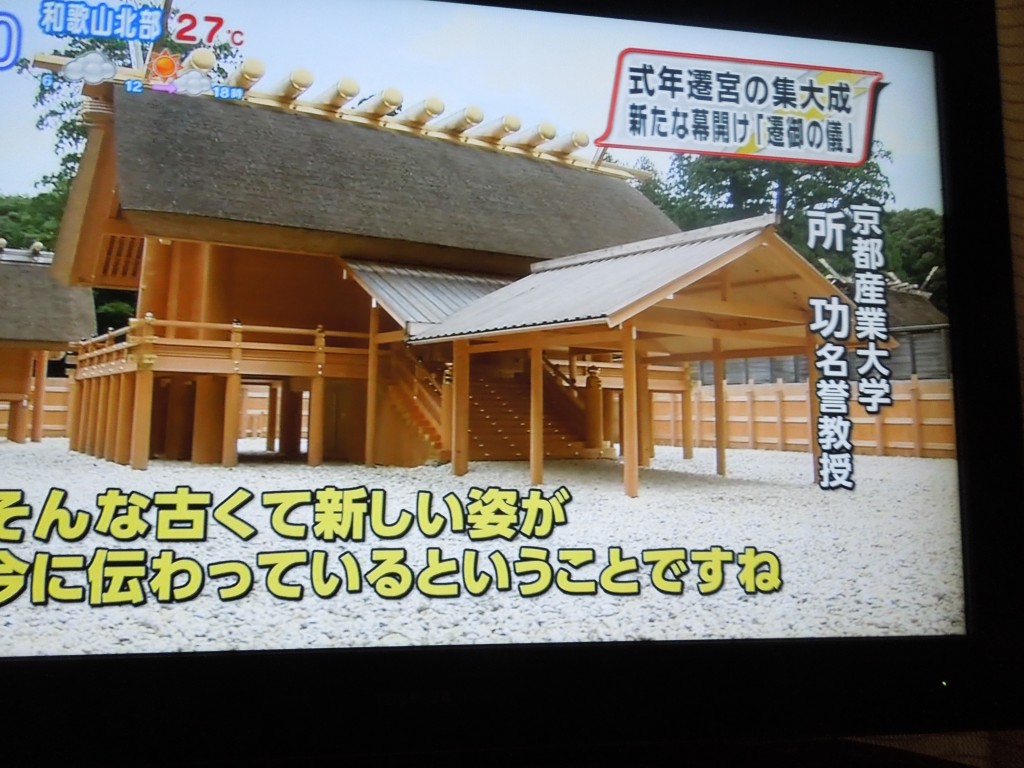

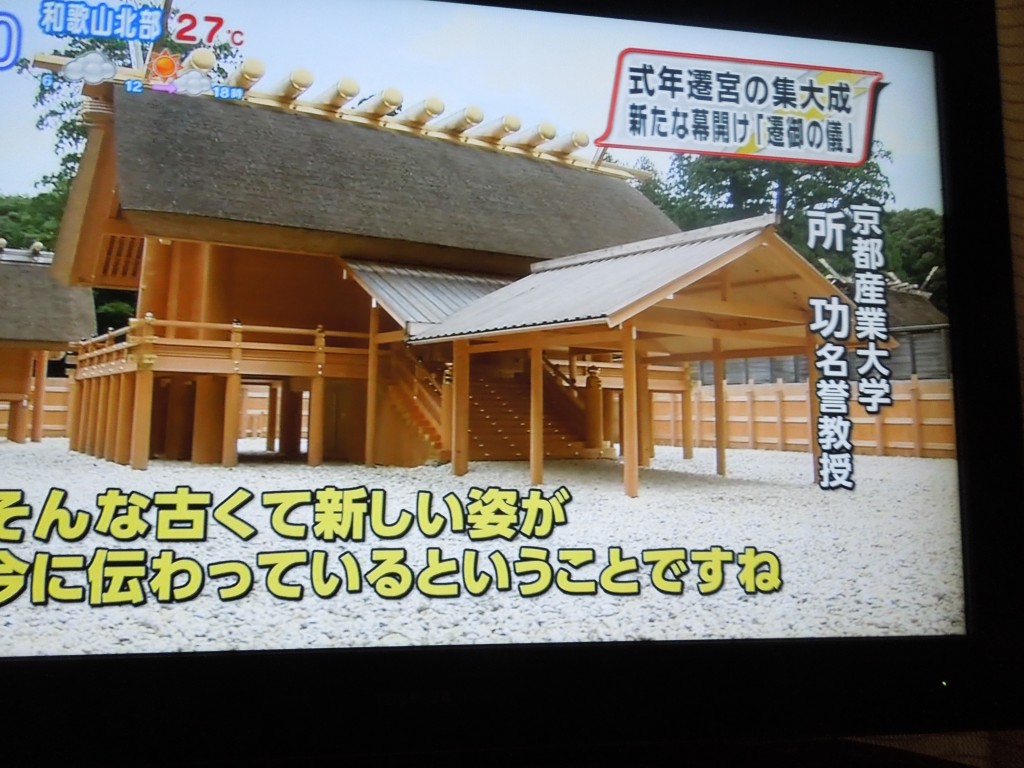

Tv coverage showing one of the many renewed offerings

**********************************************************************************************************************************************

First, there is the silence. Profound, impenetrable, and all embracing, the silence descends like a gentle cloud, enveloping everyone and everything. I sit patient and wordless, waiting for the ancient ritual of the Shikinen Sengu to begin. I am surrounded by nearly three thousand people, all guests invited to observe the Sengu, but I might as well be alone. The presence of so many others serves only to intensify the power of this awesome silence. Closing my eyes, I surrender to it, allowing the silence to sweep the crowd from my consciousness. Looking up, I gaze at the towering cryptomeria trees, silhouetted darkly against the twilight sky. For more than thirteen centuries they have stood here patiently, bearing faithful witness to the flow of pilgrims to this Shinto sanctuary and to the ceremonies that have marked the cyclical rebuilding of the Ise Shrines every twenty years. I feel utterly alone in Nature. Closing my eyes again and looking inward, I am adrift in a sea of Japanese history, a flow that extends back to the beginning of time and forward into the unknowable future. “Had I sat in this same spot a thousand years ago?” I wonder to myself. “Will I be sitting here a thousand years from now?” The silence reassures me that it will always feel the same.

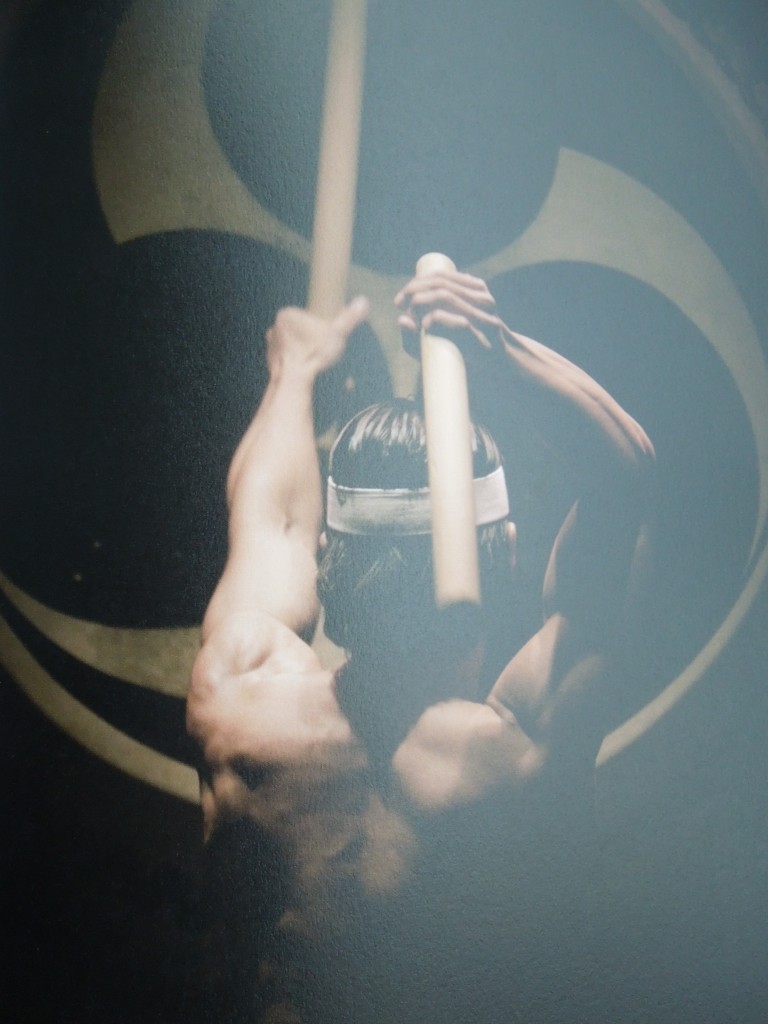

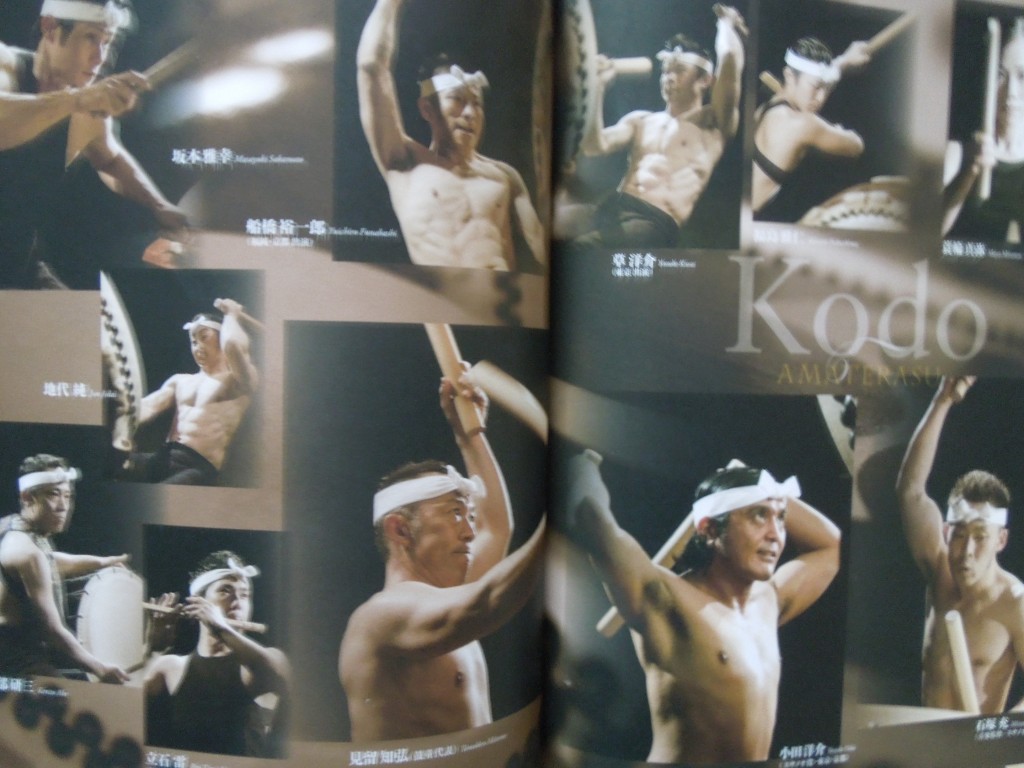

One of the preliminary rites during the Ise shikinen sengu renewal

The evening is hot and tense with expectation. Every person in the crowd has been invited to participate in the ancient rituals that celebrate the renewal of the Imperial Grand Shrines and the transfer of sacred objects from the old shrine into the new. Everyone knows that he or she is in the presence of the most sacred sanctuaries of Japan, but few know what to expect. Everyone knows that it has been exactly twenty years since the last Shikinen Sengu, but few are aware that the preparations for this evening’s events began almost as soon as the last Sengu had ended in 1993. The myriad activities that go into the rebuilding of the Grand Shrines at Ise, begun twenty years ago, had continued apace until this very moment. The passions and energies of thousands of people in hundreds of locations throughout Japan had been focused on this single date, and now it has arrived. Over two long decades, with every passing day or month or year, the tempo of preparations had slowly and imperceptibly intensified. Now, the long work was finally complete and the new shrines were about to be unveiled.

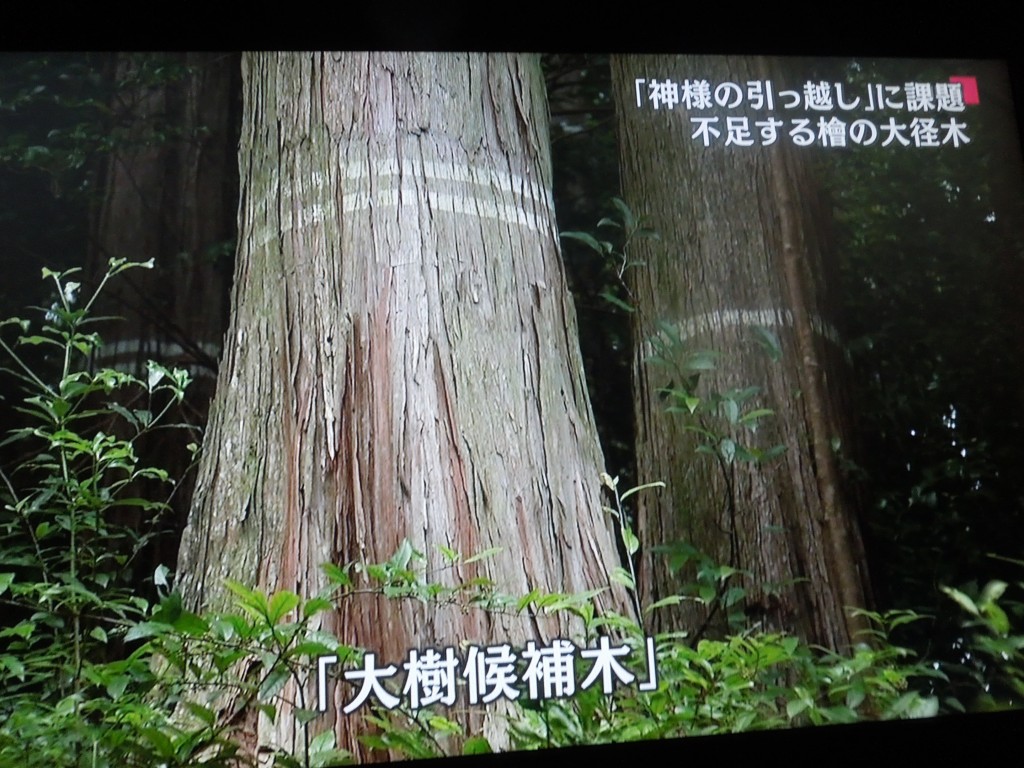

Entire forests of hinoki and sugi trees had been felled in distant forests, and each tree – tens of thousands of them – had been carefully wrapped and transported to Ise. There, the wood was first dried and cured in massive storage sheds, then sliced and planed by legions of shrine carpenters until its flat surfaces were as smooth to the touch as silk. The skill of the Ise carpenters is legendary and their daily labor of shaping the wood and cutting the joinery that holds the nail-less shrine buildings together is as dedicated as the ritual observances of the Ise priesthood. Working alongside the carpenters were scores of other craftsmen preparing the thatch for the roofs of the many shrine buildings, cutting the gold sheets used to decorate certain of the ridge poles, placing the white stones in the open spaces surrounding the shrines, attending to the millions of other architectural details that combine in the perfection of the finished shrines. Throughout Japan, hundreds of other craftsmen had been at work over the years, dedicating their superb artistry to creating objects of lacquer or ceramic, weaving fabrics or reed baskets, fashioning thousands of ritual utensils for the shrines at Ise. Twenty years ago, this day had seemed far off. Now, it is upon us.

As darkness envelops the shrines and the huge crowd of guests invited to participate in the Sengu ceremonies, the silence gives way to the insect symphony of the forest night. From time to time it is pierced by the call of a bird settling into its nest or the cry of a distant deer. The only human sounds are the occasional crunching of feet against the gravel paths as priests or guests pass by in solemn procession. First come the Ise carpenters, a cohort of more than one hundred men who have spent lives devoted to creating the sacred sanctuaries. They are considered the finest woodworkers in Japan. The youngest of them, in their thirties or forties, have worked on the Ise shrines only once. Their fathers and grandfathers are proud to have completed the rebuilding process once before, or even twice. Venerated for their superb craftsmanship, the Ise carpenters are accorded seats of special honor at the Sengu.

Television coverage of the procession of priests and dignataries

Next, Prime Minister Abe arrives, accompanied by Cabinet members and an entourage of deputy ministers and government officials. They are guided up the steep stone stairway leading to the Naiku and disappear behind the first of four fences surrounding the inner precincts of the shrine. Silence descends again, only to be broken a few moments later by a procession of Shinto priests representing major shrines all over the country. Their footsteps fade as they too are escorted up the stairs and disappear behind the fences. Again silence. Then again, the crunching footsteps of the next procession is heard approaching through the trees: this time it is Prince Akishinomiya, second son of the Emperor, leading a delegation from the Imperial Palace in Tokyo. Finally, there arrives a procession of chief priests of the Ise Shrines, a group of more than one hundred men dressed in robes of black or red, reminiscent of 12th-century court attire. They are led by Princess Sayako, daughter of the Emperor, wearing magnificent red robes. She has been designated as the special representative of the Imperial Court, and is the only woman to participate in the Sengu ceremonies. By now, the darkness of night has completely enveloped the forest, and this final procession is guided into the shrine by attendants carrying flaming torches.

For the next few hours, no one enters or leaves the shrine, and the crowd outside sits in utter silence. Not a single voice is raised, not a single chair moves (in fact, each of our chairs has been fixed to the flooring in special grooves that prevent any movement). The silence is total and profound. The movement of torches or bonfires can be seen through the shrine fences, but they are distant and silent. The only other illumination is from lanterns hung along the long avenue leading through the trees up to the main buildings of the Naiku (Inner Shrine). Standing next to each lantern is a white-garbed shrine attendant who from time to time silently replaces the candles burning in the lanterns.

Torchlight atmosphere as shown on NHK

After nearly two hours, the silence is suddenly pierced by the sound of a single flute, accompanied a moment later by the voices of chanting priests. The repetitive four notes of the flute and the constant drone of chanting priests penetrates the otherwise silent night and casts a trancelike atmosphere over the worshipers inside the shrine and the thousands of observers outside. At this point, all torches and all lanterns are extinguished and the area is plunged into total darkness. The flute and chanting continue for another quarter of an hour or so, and then – slowly and barely audible — the sound of moving footsteps begins to be heard from deep inside the shrine precincts. Moving solemnly forward, the footsteps come closer and begin to descend the stone stairway out of the shrines. A few small torches are lit to guide the feet of the priests as they descend in single file down the steep stone stairway, but almost nothing can be seen until the priests pass only a few feet from where I stand. Their chant continues, four notes whispered in constant repetition. Each priest seems to carry some object, small square boxes at first, then larger ones and long objects wrapped in white cloth. Larger boxes emerge, shrouded in white cloth and carried on poles supported on the shoulders of two priests. Then even larger boxes are carried past on the shoulders of four priests. These are the sacred objects housed in the shrine buildings within the Naiku, but the content of the boxes is unknown and their outlines can barely be discerned in the darkness. One after another, they descend the staircase emerging from the old shrine buildings, pass before us in solemn procession and then ascend the stairs leading into the new shrine and disappear. Finally, a long white curtain, held aloft by fifteen or twenty priests passes by and disappears into the new shrine. I know that within this curtain are the most sacred objects of all, but it is impossible to know their function or their size or number. Secretly, silently, they pass before me and into the darkness of the shrine.

Suddenly, only a moment after the sacred objects disappear into the shrine, a gentle breeze rustles through the trees and passes over the crowds assembled around the shrine. Soft but unmistakable, the cool fresh air washes over my face. Instantly, the breeze is also felt by everyone around me. A lump forms in my throat, and I hear muffled sobs from others nearby.

And then it is over. The transfer of the venerated objects has been accomplished. The symbols of spiritual presence have departed from the old Ise shrine buildings and have been transferred successfully into new homes. The new shrines at Ise have been fully consecrated. The old shrine buildings now stand empty and soon will be removed. Their purpose for the last twenty years has been fulfilled and they are no longer needed, except for one final, exceedingly Japanese, function. After the old buildings are carefully taken down, their enormous quantities of spent wood will be cut into small pieces, then lovingly cut into smaller fragments – some as tiny as toothpicks. Imbued with the ageless sanctity of Ise, each of these slivers of wood is wrapped in white paper and distributed to other shrines throughout Japan or presented to faithful pilgrims as talismans to carry home and preserve in the small domestic shrine (kamidana) that graces every Japanese home.

At dawn, the new shrine buildings at Ise glisten in the early morning sun. Fresh, clean and fully consecrated, they begin their twenty-year life as shelters for the deities of Sun and Agriculture. By 5:00am, more than ten thousand people have gathered at the entrance to pay their respects to the new shrines. Following the ageless rituals of the Shikinen Sengu, the shrine buildings – and with them the nation and the people of Japan — stand refreshed and renewed.

Renewed and refreshed: the newly built shrine buildings as shown in the morning news on television

One of the subshrines, Kazenomiya, with an empty space next to it awaiting the next shikinen sengu renewal in 2023. (The small box covers the mibashira around which the new shrine will be built.)