Ise's log-style architecture, exemplified in one of its smaller buildings that has been recently rebuilt

Thanks to reader, Peter Grilli, Green Shinto can confirm the dates of the “Sengyosai” or ritual transfer of sacred objects from the old shrine buildings at Ise. It is the climax of the rituals of renewal known as Shikinen Sengu, marking the culmination of a 20-year cycle.

At Naiku, the ceremony will take place on October 2, between 6:00 and 9:00pm in the evening.

At Geku, a similar ceremony will take place on the evening of October 5.

These ceremonies are not open, however, to the public except by special invitation. (For anyone planning on visiting Ise, it is worth noting that Naiku will be closed to outside visitors from 1:00pm on Oct. 2. Presumably the same will apply to Geku on Oct 5.)

****************************************

For a short explanation of the Shikinen Sengu renewal rites, click here. The Kokugakuin Encyclopedia of Shinto carries the following information by Nakanishi Masayuki (abridged from the original):

The transfer of the deity to a newly constructed shrine (sengū) in prescribed years (shikinen).

Kazenomiya; one of the many buildings that is rebuilt on the adjoining space

This major traditional project involves building anew the Main Sanctuary and other buildings of Ise Jingū, renewing all vestments and sacred treasures stored in the buildings, and transferring the deity to the new shrine.

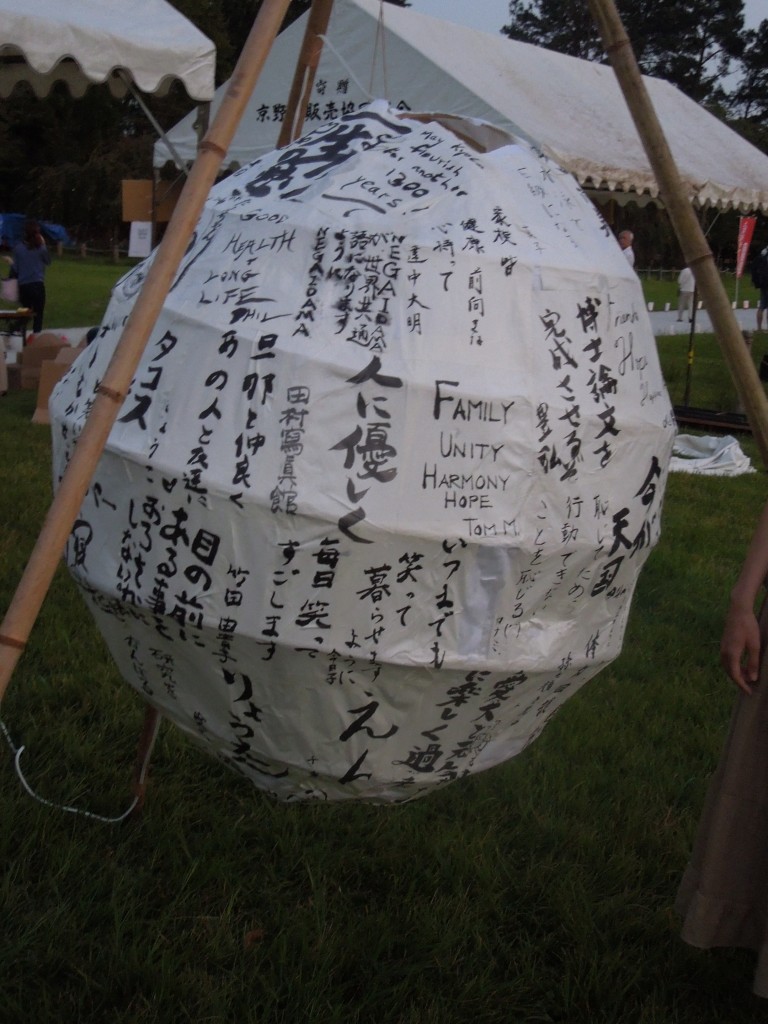

Sengū reibun provides the following definition: “The renewal and transfer of the two Grand Shrines of Ise every twenty years form the imperial family’s weightiest undertaking and a project of unparalleled scale among all the Jingū”. The sengū system was initiated at the wish of Emperor Tenmu, against the backdrop of what was the largest civil disorder of Japan’s ancient state, the Jinshin Uprising (672). During the reign of his successor Emperor Jitō, the sengū ceremony was first performed for the Inner Shrine in 690 and for the Outer Shrine in 692. Including its 61st celebration in 1993, the Shikinen sengū has been conducted for 1,300 years.

Ise Jingū’s architecture employs a unique style characterized by its linear storehouse shape, a thatched gabled roof on pillars sunk directly into the ground and an entrance on a non-gabled side. The building materials are simple, limited to cypress, miscanthus reeds and gold and copper hardware; with the ritual installation of a “sacred central post” (shin no mihashira or imibashira) beneath the Main Sanctuary’s floor. The very simplicity that is the feature of this architectural style inevitably leads to decay and dilapidation, providing a rationale for periodic renewal.

Entrance way to Ise leads through some wonderful ancient trees

Completed in eight years, the renewal process requires 14,000 pieces of timber, 25,000 sheaves of miscanthus reeds, and 122,000 shrine carpenters; this massive project reconstructs over sixty structures, including the Main Sanctuaries of the Inner and Outer Shrines, treasure houses, offering halls), sacred fences, torii gateways, the buildings of fourteen “auxiliary sanctuaries”. All offerings of vestments and sacred treasures presented by the imperial family are also replaced.

The first example of the replacement of imperial offerings dates back to 849 but the shrine’s current list totals 714 categories consisting of 1,576 articles (189 categories comprising 491 sacred treasures and 125 categories comprising 1,085 vestments). This diverse range of objects can be divided as follows. Vestments include room fittings, “kami seats” and rugs, furnishings, and ritual artifacts for the “transfer of the deity” (Sengyo) ceremony.

Sacred treasures include spinning and weaving tools, military weapons and wear, horse equipment, musical instruments, writing implements and daily goods. Reproduced every twenty years, these articles all embody skilled artistry and abundant experience and thus preserve Japanese tradition in terms of style, technique, and materials. They are thus also collectively described as “a modern equivalent of the treasures housed in Shōsōin [Todaiji treasure house in Nara].”

As the construction work progresses, various rites and ceremonies are performed at each stage of the process, including the felling and transport of timber, preparation of the construction site, and the building of shrine structures. These ceremonies can be grouped by content: the woodcutters’ ceremonies concern the felling and transport of timber; the shrine carpenters’ building rituals concern site preparation and shrine construction; and the shrine officials’ secret rituals that culminate in the Sengyo ritual.

After eight years of preparation starting with the Yamaguchi and Konomotosai ceremonies, the Sengyo ritual is held in October during the autumn of the prescribed year, forming the core of the Sengū celebrations. While the deity is being transferred in the dark, the imperial envoy proclaims “shutsugyo” three times to announce the august departure of the deity to the new shrine. At the same time, at the imperial palace, the emperor faces the direction of Ise and performs a “ritual of distant worship”.

Purification: Ise's sacred river serves as a natural temizuya

Kasuga School

Kasuga School