This is the last in my mini-series on Hindu connections with Shinto, because I’ve now come across a page that carries a comprehensive overview of all the various links between Hinduism and Japanese culture. My purpose in drawing attention to the little known connection was to show how deeply entwined in continental beliefs Shinto is, rather than the ‘unique’ indigenous religion that nationalists like to portray.

Here is the page in question, which is a remarkable catalogue of facts and quotations:

http://www.hinduwisdom.info/Glimpses_XVII.htm

Someone has put an awful lot of work into the page, so I looked up the author. “My name is Sushama Londhe. I am an Indian-American who came to the U.S. as a graduate student 30 years ago, and I have settled here for good. This site is my personal endeavor to provide appropriate collection of information about Hinduism, as well as to attain a correct appraisal of India’s rich cultural heritage..” http://www.hinduwisdom.info/index.htm

Below I’ve included just a few highlights from the page……

*************************************

The belief prevalent in ancient Japan that there lived a rabbit in the moon was probably an outcome of the Indian influence.

Dr. D. T. (Daisetz Teitaro) Suzuki (1870-1966) was a Japanese Buddhist and Zen scholar, who has written several books, including Zen Buddhism and Its Influence on Japanese Culture. He said: “The study of Japanese thought is the study of Indian thought”.

Izanagi and Izanami churn the primordial liquid

Donald A. Mackenzie (1873 – 1936) author of Myths of Pre-Columbian America has written: “The Indian form of myth of The Churning of the Milky Ocean reached Japan. In a Japanese illustration of it the mountain rests on a tortoise, and the supreme god sits on the summit, grasping in one of his hands a water vase.

The Japanese Shinto myth of creation, as related in the Ko-ji-ki and Nihon-gi, is likewise a churning myth. Twin deities, Izanagi, the god, and Izanami, the goddess, sand on “the floating bridge of heaven” and thrust into the ocean beneath the “Jewel Spear of Heaven”. With this pestle they churn the primeval waters until they curdle and form land.”

Dr. Subhash Kak (1949 – ) is a widely known scientist and a Indic scholar. He writes: “Vedic ideas were also taken to Japan by the sea route from South India and Southeast Asia . That serves to explain the specific transformations of some Sanskrit terms into Japanese through Tamil phonology. For example, consider the transformation of Sanskrit homa, the Vedic fire rite, into Japanese goma, where the initiation is given by the achari (Sanskrit ācārya). The Sanskrit mantras in Japan are written in the Siddham script of South India .”

Indra, god of thunder found in the Rig Veda, is adored in Japan as Taishakuten.

Ganesha, the Indian god of wisdom, who has the head of an elephant and the trunk of a human being, is worshipped under the name of Sho-ten, (literally, Holy God), in many Buddhist temples, as one who confers happiness upon its votaries, especially in love affairs. In Japan we very often find figures of two Ganeshas, male and female, embracing each other (Mithuna).

The Japanese sea-serpent, worshipped by sailors, is called Ryugin/Ryujin, a Chinese equivalent of the Indian Naga.

Suiten (water-god) is a Shintoist name. But the god, widely worshipped by people in downtown Tokyo, was originally Varuna (water-god in India) and was introduced into the Buddhist Pantheon by esoteric Buddhism, and then adopted by Shintoists, though Shintoists may hesitate to agree with this explanation. Kompira, a god of sailors, is worshipped at Kotohira Shrine, in Kagawa Prefecture, on the island of Shikoku. Kompira is corrupt form of Kumbhira, a Sanskrit word for crocodile in the Ganges. Ben-ten (literally, Goddess of Speech) is the Chinese and Japanese equivalent of Saraswati.

Benten, the biwa player, who originated as the Hindu deity Saraswati

“Shintoism has been designated by some scholars as the Japanese version of Hinduism” – Chaman Lal.

The Hindu deities in course of time again passed through another phase of transformation to suit the Japanese thoughts and ideas, and many of these transformed deities gained highly revered positions which they had never before attained either in India or China.

In fact, several minor gods and goddesses who were too insignificant to merit careful attention in India, attained a considerably exalted position in Japanese Buddhist pantheon. It is commonly believed in Japan that the Hindu deities if worshipped properly, bestow quickly material benefits and other favors in day to day life on their devotees rather than any spiritual gain. This has made these gods and goddesses very popular in Japan as “the common people are more interested in worldly or material benefits than in the so-called abstract spiritual achievement.”

Co-existence of the native Shinto and Indian Buddhists and Vedic deities in the same temple was, and is a common feature in Japan. Like Buddhism, Tantricism, an inseparable part of Hinduism spread far beyond the boundaries of India, Nepal, Tibet and Burma. Thus, we find that the Hindu gods who were incorporated into Indian Buddhism gradually found their way to China and then to Japan where many of these Hindu deities found a status which they had never attained either in India or China. (source: India and Japan: A Study in interaction during 5th cent – 14th century – By Upendra Thakur p. 27 – 41).

‘Many fragments of the Japanese myth-mass were unmistakably Indian. The original homeland of the first man and women of Japanese mythology is said to have been in the Earth-Residence-Pillar i.e. Mount Meru of Indian mythology. There is another story of Buro-no-Kami whose identity has been established with the deity called Brave-Swift-Impetuous-male. This Kami may be none other than the Indian deity Gavagriva, the Ox-head deity. The story recounts in the style of the Jatakas how the deity punished the heartless rich brother and rewarded the king hearted poor brother. In India one of the names of the moon is Sasanka (lit. having a rabbit in the lap) and there is an ancient Indian legend why it is so called. The belief prevalent in ancient Japan that there lived a rabbit in the moon was probably an outcome of the Indian influence.

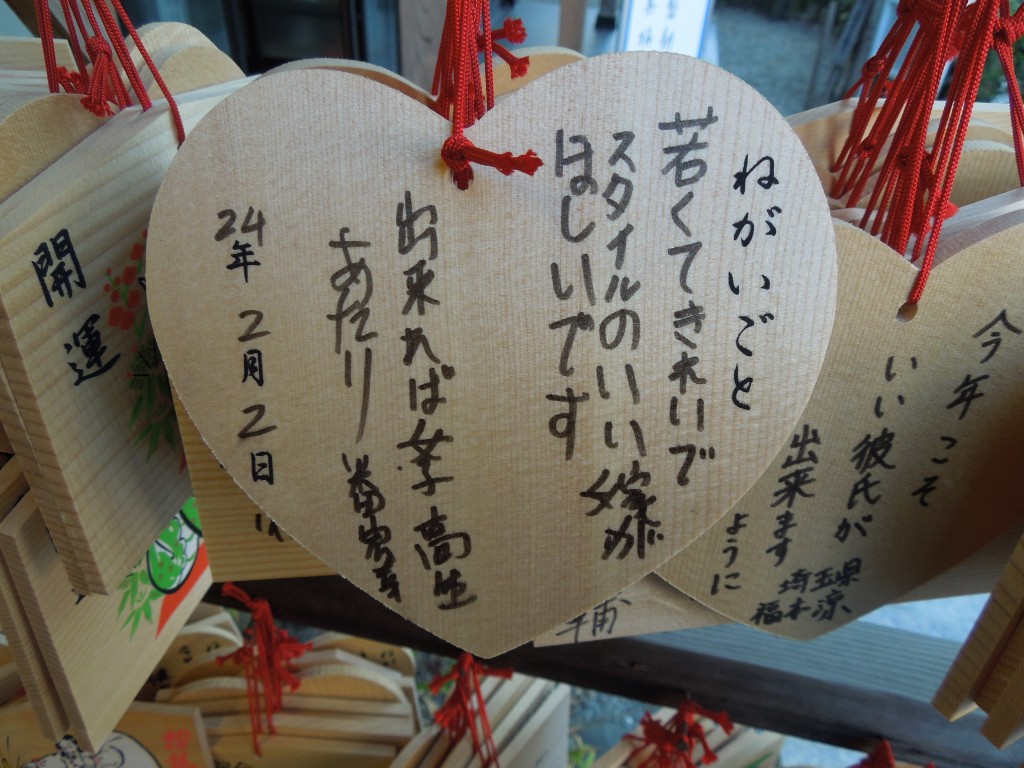

Some Japanese warriors in medieval Japan went to the battle ground with helmets bearing Sanskrit characters for blessing (mangala) on their heads. While scaling the sacred Mt. Ongake as a religious observance, the Japanese climbers wearing traditional white dress have inscribed on their robes Sanskrit Saiddham characters of early type. Sometimes they put on white Japanese scarfs (tenugui) carrying Sanskrit character Om, the sacred sound symbols of the Hindus.

One can also see the influence of the Indian epic Ramayana in the traditional Japanese dance forms of ‘Bugaku’ and ‘Gigaku’

Does sacred dance have its origins in India too?

Apart from the widely known fact that Buddhism in Japan has its origin in India , not many probably know that so many Hindu deities surround the life of a Japanese. Speaking at a lecture titled ‘Hindu Gods and Goddesses rooted to Japan’ here Friday, Lokesh Chandra, the director of International Academy of Indian Culture, highlighted how deeply Indian religion and culture has influenced Japanese culture and tradition over the past centuries. He said that many temples across Japan are full of Hindu deities.

Together with Hindu gods and goddess, ancient Japanese society was also introduced to Indian dance forms and musical instruments. A typical example is the ‘ Biwa ‘,which actually had its origin from the Indian ‘Veena’.

“It is the Mantrayana sect of Buddhism emphasising mantras (chants) and rituals through which Hindu deities reached Japan,” Dr Chandra said. “The Japanese also perform “homa” known as “goma” to their deities even today, they get ghee flown from Australia,” he added.

Philipp Franz von Siebold (1796 – 1866) German scholar has written that in 1832 there were 131 Shrines dedicated to Goddess Sarasvati and 100 to Lord Ganesha in Tokyo itself .

The earliest known music dance of Japan is Gigaku a kind of mask-play which Mimashi brought to Japan from Korea in 1200 AD. This art (Gigaku) was of Indian origin as indicated by masks representing Indian features which are still preserved in a considerable number in the temples of Nara. There were characters among the dancers who represented a lion and an eagle which does suggest links with India, because in China and Japan there were no lions. Moreover, the term for the eagle character is Karuna which is nothing but the derivative of the Sanskrit world Garuda.

The Goma ceremony, here performed by Shogo-in yamabushi, originated in India

For an academic paper on the subject, see Medieval Shinto as a form of ‘Japanese Hinduism’