Kyoto's Yasaka Jinja, known popularly as Gion-sha and once part of a syncretic complex which worshipped Gozu Tenno

Before its conversion to a ‘purely’ Shinto shrine by Meiji nationalists, Yasaka Jinja in Kyoto was a syncretic miyadera (shrine run by a temple), under the control of the Tendai sect on nearby Mt Hiei. The main deity worshipped was a curious ox-headed deity called Gozu Tenno.

In Shinto Shrines p. 144, Joseph Cali has an excellent overview of the cult of Gozu Tenno, described as ‘an Indian-Buddhist-Shinto syncretic deity with the power to protect against (or cause) illness.’

The early history of Yasaka Shrine is uncertain, but Cali says it is clear that the deities worshipped on the site were a mix of both Buddhist and Shinto from ancient times. The temple area was called Gion, named after the first monastery in India built for the Buddha (Jetavana Vihara was translated into Japanese as Gion Shoja).

The protector of the Indian monastery was the ox-headed deity Gavagriva, known in Japanese as Gozu Tenno. According to legend he gave a prince some magical grass which he wore around his waist to protect himself from disease. This became the origin of the chinowa ring, used today in midsummer purification rites.

In 869 a severe outbreak of pestilence was attributed to the anger of Gozu Tenno, and a great festival was organised by the authorities to appease the deity. Sixty-six halberds were raised in the imperial garden of Shinsen-en, representing the sixty-six provinces of Japan. It was the origin of the Gion Matsuri, which became a yearly event from 975.

According to the Encyclopedia of Shinto, “With origins as a spirit causing disease, Gozu Tennō was in time transformed into a tutelary that protected its worshipers from such epidemics, taking on further characteristics as a deity of justice, a deity that ascertained truth, and a deity of the cardinal directions. As observances of the Gion-e type spread regionally, Gozu Tennō was also established as a local tutelary deity (chinju no kami).”

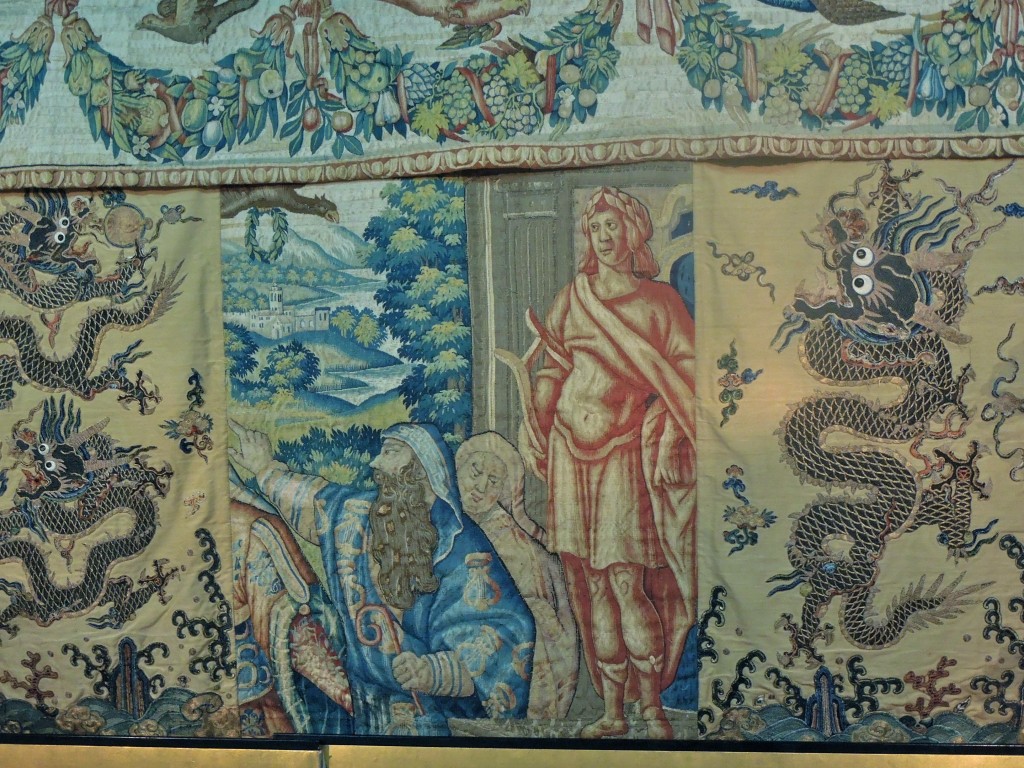

A variety of ritual formulae and sacred histories purport to explain the origins and nature of Gozu Tennō; historically originating in India, the deity’s features underwent successive transformations and systematic development as it was transmitted to China and Japan. The actual details of its transmission and the process of amalgamation with other deities, however, are complex issues and not universally agreed upon. In India, the deity was called Gosirsa Devaraja, a minor tutelary deity in Buddhism known as a protector of the Monastery of the “Jeta Grove” (known in Japan as Gion), while in Tibet it was known as the deity of “Ox-Head Mountain” (Jp. Gozusan). Transmitted to China, the deity’s cult merged with esoteric Buddhism, Daoism, and Yin-Yang beliefs, and then was transmitted to Japan, where it experienced further mingling with Japanese Yin-Yang (Onmyōdō) divination.

The concept underlying the Gion Festival has to do with turning vengeful spirits into protective deities by placating and pleasing them with entertainment. This is known as goryo-e (meeting with angry spirits). It stemmed from the Buddhist notion that kami were in need of enlightenment, a teaching that enabled Buddhist priests to assert supremacy over Shinto in the same way as they had done previously in India with Hinduism.

Susanoo, the storm god, here slaying the eight-headed Orochi monster

At some point the imported Hindu deity became identified with Susanoo no mikoto, the Japanese storm god who was also associated with disease (pestilence was carried on the wind). When the Meiji nationalists insisted on a clean separation of Shinto and Buddhism, they specifically cited Gozu Tenno as an example of the ‘distortion’ of Shinto.

A renamed Yasaka Jinja was therefore forced to give up worship of Gozu Tenno for Susanoo no mikoto. The shrine’s new name was a reference to the Yasaka clan of Korean immigrants who had settled in the area, and today it stands at the head of around 3000 Yasaka Shrines nationwide.

The old Buddhist-Shinto fusion is not forgotten however, and lives on in the festival where floats are full of syncretic practice. (For an example, see the En no Gyoja float here.) Also every school child learns by heart a passage in the Tale of the Heike about the old temple bell that rang out over the area: “The bell of the Gion temple tolls into every man’s heart to warn him that all is vanity and evanescence.” (The bell is housed now at Daiun-in temple.)

In the sound of the Gion bell were echoed the Hindu origins of Gozu Tenno.

The Gion Matsuri – first inspired by appeasement of an imported Hindu deity

Of the eight shrines in the World Heritage registration, Fujisan Hongu Sengen Taisha is the most important. Established at its present location in 806, it boasts an unusual two-storey sanctuary as well as ponds fed by underground water from Mt Fuji. It stands at the head of some 1300 Sengen shrines nationwide.

Of the eight shrines in the World Heritage registration, Fujisan Hongu Sengen Taisha is the most important. Established at its present location in 806, it boasts an unusual two-storey sanctuary as well as ponds fed by underground water from Mt Fuji. It stands at the head of some 1300 Sengen shrines nationwide.