The most sacred mountain in Japan has now achieved World Heritage status. Apparently the delegates in Cambodia have given it official approval as Japan’s 17th World Heritage site. It’s undoubtedly the most famous of them all.

Green Shinto friend, Ted Taylor, has a well-timed article today in the Japan Times, giving an overview of the cultural associations of the mountain, along with its role as a sacred symbol. The cultural aspect was a key factor in the mountain’s registration and achievement of World Heritage status.

***********************************************************

Mount Fuji has long been an icon

BY TED TAYLOR SPECIAL TO THE JAPAN TIMES JUN 23, 2013

In the land of Yamato,

It is our treasure, our tutelary god.

It never tires our eyes to look up

To the lofty peak of Mount Fuji

—Manyoshu

'Sankin kotai' procession, on its way back from Edo and views of Mt Fuji (courtesy Japan This blog)

In 1635, the third Tokugawa shogun, Tokugawa Iemitsu created what was known as sankin-kotai (system of alternate residence duty). This required the daimyo (feudal lords) to reside for part of the year in the capital. Although the lords could return to their domains, they had to leave their wives and families in Edo in order to ensure their loyalty to the shogunate. The daimyo were made to use highways designated by the shogun, the best known of these being the Tokaido and the Nakasendo.

The Tokaido connected Kyoto with Edo, running along the seacoast of Honshu. The daimyo who traveled the highway did so accompanied by enormous retinues, as befitting their status. A prominent feature of the Tokaido would have of course been Mount Fuji, whose distinct shape accompanied the processions over a number of days.

With their elaborate road systems, the Tokugawa had also created a “culture of movement.” Pilgrims followed the Tokaido back and forth to the pilgrimage sites of Ise in what is today Mie Prefecture. This led to an increase in travel literature, both in the form of travel guides and ukiyo-e. The artist Hiroshige is the name most associated with the Tokaido, and his work “The Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido,” stands as the best sold series of ukiyo-e prints. It is said of Hiroshige that he was “perhaps less an artist of Nature than of the culture of nature.” His colorful images helped place Mount Fuji at the center of the Japanese consciousness.

As Edo grew, so did Mount Fuji’s reputation. Helping promote this were the many Fuji pilgrims and pilgrimage associations, known as fujiko. Along with the prerequisite temples associated with these groups, they also constructed artifices know as fujizaka. These miniature Mount Fuji’s were constructed from rocks and plants taken from the mountain itself. Soil from the actual summit of Japan’s highest mountain was placed on the summit of the fujizaka, in order to harness some of the spiritual power of the volcano.

Many pilgrims no longer had to go to the mountain, as the mountain had now come to them. At the height of the Edo Period (1603-1867), there were more than 200 fujizaka, and none have been constructed since the 1930s. Fifty-six survive today, including those at Teppozu Inari Shrine in Tokyo’s Hatchobori district, and Hatomori Shrine in Sendagaya.

Many pilgrims no longer had to go to the mountain, as the mountain had now come to them. At the height of the Edo Period (1603-1867), there were more than 200 fujizaka, and none have been constructed since the 1930s. Fifty-six survive today, including those at Teppozu Inari Shrine in Tokyo’s Hatchobori district, and Hatomori Shrine in Sendagaya.

During their stay in Edo, the daimyo lived in large estates across the capital, many of which had extensive grounds. More than one daimyo had a small hill known as a fujimizaka built upon the grounds in which to climb and observe Mount Fuji. Since the earliest times, mountains had been climbed in order to survey the land. These viewings were ritualistic, but also had certain political motives, as it was a symbolic controlling or pacifying of the land. A good example is at the Hama-rikyu Garden in Tokyo’s Chuo Ward.

The term fujimizaka is also shared by many of the hills around the city. Meaning literally hill from which to see Fuji, these spots had traditionally offered the best views of the mountains. Sadly in modern Tokyo, these views have been disappearing, with the coming of the modern high-rise. The final possible view of the mountain, albeit a modest section of Fuji’s northern slope, is about to be lost to yet another construction project.

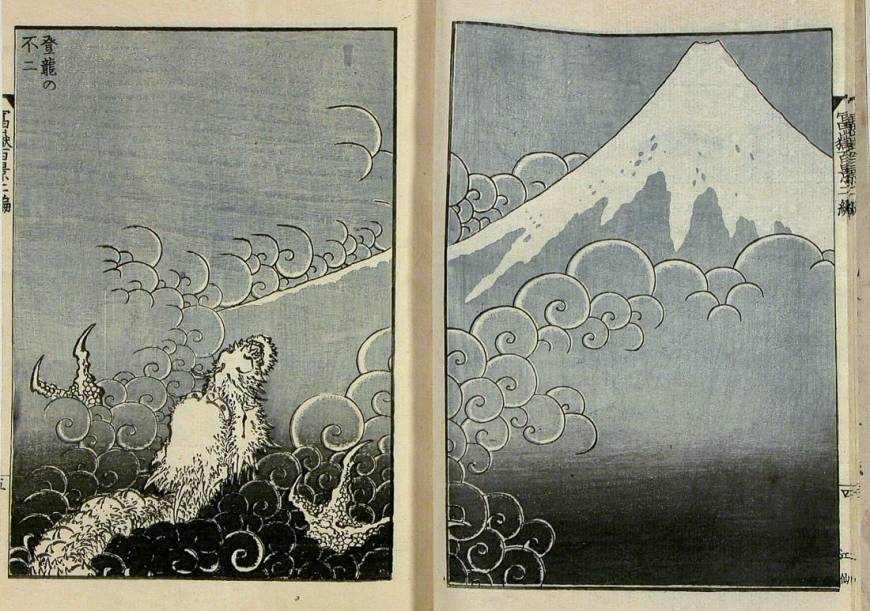

Along with the fujiko and their fujizaka, ukiyo-e served as the third form of media that led to the urban appreciation of Mount Fuji. Hiroshige’s contemporary, Katsushika Hokusai, found the mountain to be his greatest muse, publishing two great works of the subject. His “One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji” set the mountain as a common feature across the Edo landscape — on the horizon, between buildings, through a window — emphasizing the relationship between the lair of the gods and the shogun’s city. The face of Hokusai’s Fuji is seen from every angle, with the commonality between them all being Hokusai and the viewer.

With the fall of the Shogunate and the end of the feudal period in 1868, “Westernization” came into vogue, and traditional Japanese arts and crafts were considered old-fashioned and hackneyed. Ukiyo-e had lost their value to the point that they were used as packing materials. In this way, they came into possession of Europeans, and served as a source of inspiration for the impressionist, cubist and post-impressionist art movements. Claude Monet was particularly influenced by the strong colors and lack of perspective, and Vincent van Gogh was known to have owned a copy of Hiroshige’s “53 Stations of the Tokaido Road.”

Mount Fuji as a common motif of ukiyo-e was thus exported through these prints to become an understood icon of Japan. European travelers of the period longed for their first shipboard view of the mountain, which no doubt signified the end of a long sea voyage.

********************************************************************

For more on the sankin-kotai (alternative residence system of the daimyo), see here. For Hokusai’s images of Fuji, see here. For the Wikipedia page on his 36 Views of Fuji, see here.

*****************************************************************(*

Dragon ascending Mt Fuji, from Hokusai's "One Hundred Views of Mt Fuji'

Bishamonten can sometimes be seen in Shinto shrines as one of the Seven Lucky Gods. He’s recognisable by the pagoda he holds in one hand and often a spear in the other. He is closely associated with the north, of which he is the guardian.

Bishamonten can sometimes be seen in Shinto shrines as one of the Seven Lucky Gods. He’s recognisable by the pagoda he holds in one hand and often a spear in the other. He is closely associated with the north, of which he is the guardian.