A Konpira shrine with Buddhist statue to the left of the altar, indicative of its syncretic nature

Kompira (or Konpira) is one of the more popular kami in Japan, associated with the sea and with its main shrine of Kotohira-gu in Shikoku (known popularly as Konpira-san). The deity is said to be derived from Kumbhira, a Hindu crocodile god of the Ganges River. But what on earth would a crocodile god associated with the river Ganges be doing in Japan?

Well, it seems the truth of the matter is hard to come by, since various accounts exist. The Kokugakuin encyclopedia has this to say (Mount Zozu is the hill in Shikoku where Kotohira stands);

The deity of Konpira is a Japanese kami, but there is Buddhist influence on the Konpira faith at Mount Zōzu and the area was also a site of Shugendō activity. During the Edo Period the Indian deity Kumbhīra (a dragon king sea deity who protected the palace) was conflated with Konpira, and the cult spread along with the development of shipping and the creation of transportation networks.

For another version, I turned to Cali’s description in Shinto Shrines. Worship of a thunder deity existed on the mountain from at least the thirteenth century, he writes. Buddhist temples were erected, and it was not until 1575 that a shrine to Konpira was put up by a Shingon monk called Yuga motivated by mention in the Golden Light Sutra of Kompira/Kumbhira as an Indian protector of Buddhism.

In later times the mountain became a strong shugendo centre, but in 1872 the Meiji government broke up the complex. Shugendo was outlawed, and Buddhist names and objects removed from the shrine. In their place the kami Omononushi together with Emperor Sutoku were enshrined, to be known collectively as the Kotohira deity.

*************************************************************

The following is adapted from an article in Encyclopedia of Monasticism by Steve McCarty. For the full article , see http://www.waoe.org/steve/syncretism.html

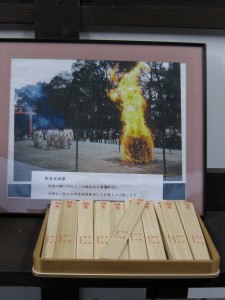

A statue of the Buddhist-protecting Hindu deity, Kumbhira

Kompira-san is thought to have been a seafaring capital of ancient Japan, worshiping a sea god (kami). Such sites could be termed proto-Shinto, reflecting the fact that Shintoism was late to institutionalize in response to Buddhism.

In Zentsuji some Kofun period tumuli have been turned into Shinto shrines as conduits to the kami (shintai), uniting ancestors with gods over millennia. Moreover, indigenous animism viewed a mountain such as Mount Kompira (or Zozuzan, Elephant’s Head Mountain) as itself the body of a god (shintaizan).

Into this entered esoteric Buddhism, reinforcing the deeper stratum of mountain worship by associating each temple with a mountain. A religious pluralism maintained that native deities emanated from original Buddhas (honji suijaku setsu).

Bureaucratic restrictions on the number of monks that could be ordained led to spontaneous forms of Buddhism that favored mountain asceticism (especially Shugendo). Mount Kumano and Mount Hiei demonstrate how geography was organized into a mandala of Buddhist-Shinto syncretism that the ritual practitioner could traverse.

Similarly at Mount Kompira, the Buddhist guardian Kumbhira, originally a Hindu crocodile god of the Ganges River, was said to have flown to Japan and became Kompira. He was accompanied by Elephant’s Head Mountain near Bodh Gaya, which figures in the hagiography of the Buddha. (Mount Kompira does indeed resemble an elephant’s head, although not as much as conventionalized views by Hiroshige and other artists.)

Given the animism of mountain worship, kami were perceived in Hindu fashion as riders on their mounts. Beyond being a crocodile god, suitable to protect seafarers, Kompira was elevated to a Great Incarnation of the Buddha (daigongen). Anthropomorphic iconography exists of Kompira Daigongen riding the mountain in the form of a white elephant – a creature associated with the Buddha, having served also as the mount of the ancient Hindu god Indra. [White is a standard animist/ shamanic sign of purity and distinctiveness amongst animals.]

In time Kompira Daigongen became identified with the Shinto kami worshipped at Mount Kompira, O-kuni-nushi-no-mikoto, one of the founding gods of Japan who was vaguely associated with crocodiles in the White Hare of Inaba myth in the Kojiki. When the Meiji government insisted on separating Buddhism and Shinto, the one-time temple of Konpira chose to become a shrine. It remains today a syncretic faith, which may explain why it’s not part of Jinja Honcho.

Kotohira-gu in Shikoku, head shrine of Kompira worship across Japan

A double dose of guidance offers more than usual information

A double dose of guidance offers more than usual information