MAY 16, 2013 Japan Times

“The number of Shinto shrines in Japan has changed over centuries due to various political and social changes. There were about 190,000 shrines during the early Meiji Era (1867-1912), before a drastic change came about in the merging of shrines and temples. The number of shrines was greatly reduced, and now there are only around 80,000. That’s not much more than the number of convenience stores across Japan.”

This is how Tsunekiyo Tanaka, president of Jinja Honcho (Association of Shinto Shrines) began a lecture — with a little humor. Established after World War II, Jinja Honcho was created to supervise Shinto shrines throughout in Japan, and Tanaka was speaking at a recent special public event hosted by “The Grand Exhibition of Sacred Treasures from Shinto Shrines” at the Tokyo National Museum.

Accessory box with maki-e lacquer and plum blossom design (courtesy Japan Times)

The exhibition celebrates the 62nd “grand relocation” of the Ise Grand Shrine and is being held with special assistance from Jinja Honcho and with the cooperation of numerous individual shrines throughout Japan.

Although Shinto, the way of kami (gods), is believed to be an indigenous faith of Japan, few Japanese are devoted Shintoists. Instead, many visit Buddhist temples as well as pray for luck and happiness at Shinto shrines. It is believed that before Buddhism was introduced in Japan, however, Shinto was born from an existing primitive form of religion that worshipped nature.

The ancient people of Japan honored sacred spirits that they recognized in nature, manifesting in mountains, rocks, rivers and trees. As communities grew, they began erecting shrines where they could worship these deities, and the shrines became centers of regional life and culture.

The arrival of Buddhism, however, brought with it stylistic carved figural icons, an art form that influenced Shinto imagery, and as Shinto-Buddhist syncretism progressed, many Shinto shrines and their deities were combined with Buddhist temples and figures. Even Japanese who still follow Shinto find it difficult to grasp what it really means, although many Japanese customs, such as an emphasis on purification and aesthetics in harmony with nature, appear to be derived from Shinto.

Tanaka, a Shinto priest of Iwashimizu Hachimangu, Kyoto, explained it as simply as he can: “In comparison to Western religions, such as Christianity, for which people believe in an absolute God, followers of Shinto sense kehai (presence of spirits) in the nature.

“Shinto never had holy scriptures like the bible to follow, nor does it have a doctrine. It’s more of a way of living, or the wisdom of how to live in harmony with the nature, while being grateful and respectful of all the spirits of life,” he continued. “Shinto has permeated everyday life in such a way that most people are not particularly conscious of its influence.”

Omusubi (rice balls), for example, originally symbolized the tying of the “souls” of ine (rice plants), which themselves are believed to be inherited from kami.

Child-bearing magatama beads found at the Okinoshima site in Kyushu (courtesy Japan Times)

“You take firm hold of the rice, the souls, and mold them with both hands, which have been purified with a little salt and water,” Tanaka said. “Mothers’ hands are ideal to make omusubi, as the mother represents life, love and care. Now, though, people often buy omusubi at convenience stores.”

As Tanaka explained in his talk, it is rare to have the relocation of two major shrines, Ise and Izumo, in the same year — and so he hopes these events will help “revive the relationship between people and kami by evoking the awareness of its tradition and rich cultural background”

Ise Grand shrine in Mie Prefecture, the most venerated of shrines in Japan, is dedicated to Amaterasu, the Sun Goddess, who, according to myth, is the original ancestor of the imperial family. The first relocation ceremony of Ise was in 690 AD, and since then the ritual is repeated every 20 years. It involves the temporary relocation of the shrine’s kami during the renovation of the grounds’ buildings. The procedure not only ensures the preservation the original design of the shrine, but it also gives craftsmen the opportunity to showcase and pass down their skills to the next generation.

“It is believed that the kami are also rejuvenated through the renewal of buildings and furnishings,” said Hiroshi Ikeda, special research chair of the Tokyo National Museum. “And that implies the idea of everlasting youth, known as tokowaka.”

Numerous sacred treasures — including 160 designated National Treasures and Important Cultural Properties — from various shrines have been brought together for this commemoration of Ise’s grand relocation. Unprecedented in scale and scope, the exhibition showcases Shinto artworks that vary from symbolic objects such as a bronze mirror and Japanese magatama beads, to more practical items including arms and armor, beautifully embroidered garments, furniture, a writing box and an accessory box complete with a toiletries set of combs decorated with mother-of-pearl inlay and maki-e lacquer.

“The sacred treasure items are often oversized or undersized, emphasizing that they were not for human use,” Ikeda explained. “They emulated the styles once popular in the residences of imperial and aristocratic families, and so such objects came to represent court society life and aesthetics, from which Japanese style, known as wayo developed.”

A 'shinzo' representation of a kami (courtesy Japan Times)

Ikeda went on to explain that shinzo, (Shinto kami statues), were also made in the style of Japan’s aristocrats. Kami, which were originally understood to be invisible and intangible deities, first began to be represented in figural form in the 8th century, because of the influence of popular Buddhist statues.

“The earliest surviving examples of Shinto statues date from the 9th century,” Ikeda said. “And as there were no iconographic rules for Shinto kami statues, as there are for Buddhist ones, they were represented more freely, modeling court style.

Other sections of the exhibition focus on discoveries at ceremonial sites that indicate the beginnings of a ritual celebration of kami, and on objects — including costumes, instruments and masks — used at ceremonial performances at festivals. Such rituals involved asking kami and ancestral spirits for divine protection, and praying or giving thanks for peace and a bountiful harvest.

At festivals, specially prepared foods were presented as offerings, to be enjoyed alongside a variety of ceremonial performances, including music, dance and Noh plays. All of this harks back to the original purpose of food and performing arts in Shinto — the idea that those involved in the preparation of food and musical or Noh activities would devote themselves to the skills of their art form to please kami, with the belief that kami also reside in the highest achievement of art.

In the words of Tanaka: “In Japan, anything in your life can be the ‘way’ of something, or a discipline, which is something I believe was influenced by Shinto. Take for example, the way of the sword, calligraphy, singing, or even cooking noodles — these can be accomplished with the sincere aim of excelling to the highest achievement, the results of which can be only offered to kami.”

*****************************************************************************

“Grand Exhibition of Sacred Treasures from Shinto Shrines” at the Tokyo National Museum runs till June 2; open 9:30 a.m.- 5 p.m. (Fri. till 8 p.m., Sat, Sun till 6 p.m.) ¥1,500. Closed Mon. www.tnm.jp The exhibition next venue will be the Kyushu National Museum from Jan. 15-March 9, 2014.

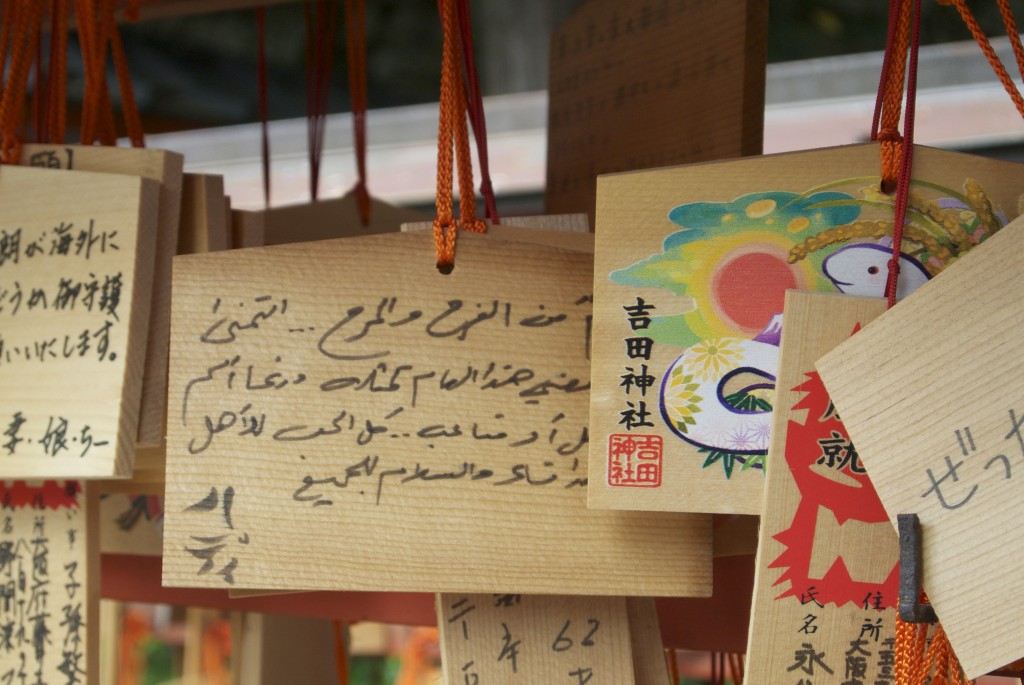

The Way of Slicing Fish - a demonstration at Yoshida Shrine in Kyoto. “In Japan, anything in your life can be the ‘way’ of something, or a discipline, which is something I believe was influenced by Shinto."