An attractive Benzaiten shrine in the Saito compound of Hiei's Enryaku-ji

Mt Koya and Mt Hiei are the twin peaks of Japan’s esoteric Buddhism. Mt Koya houses the head temple of Shingon, and Mt Hiei that of the Tendai sect. Both complexes are much smaller now than they were in the past, and in the middle ages they counted amongst the greatest mountain temples in the world. Both are now World Heritage sites.

The Tenjin ox welcomes visitors on the way to Enryaku-ji's main building, the Konponchudo

Shingon and Tendai both acknowledge kami and take a combinatory approach. I recently posted an article on the shrines that were a part of Kukai’s original project on Koyasan. Today I visited Hieisan and took photos of some of the small shrines that stand amongst the large temple buildings.

It’s been a while since I was last up on the mountain, and as ever I was impressed by the huge scale and the sense of history that the area exudes. I was also heartened to see several monuments and noticeboards affirming commonality with China and Korea.

Hieisan’s main shrine of course is the atmospheric Hiyoshi Taisha, towards the bottom of the mountain on the Sakamoto side. Joseph Cali has written of it in Shinto Shrines, from which the following quotation is taken:

It’s said that in the eighth century, Saicho’s devoted Buddhist father prayed to the kami of Hiei for a son. When his prayers were answered, he built a small shrine at the foot of the mountain and dedicated it to the kami. His son came to the mountain to worship as a Buddhist priest and began to worship here before the new capital of Heian-kyo (Kyoto) was founded in 794.

The temple Saicho established (known as Enryaku-ji, was appointed protector of the new capital, partly because it guarded the north-east corner through which the devil was likely to slip. It meant that Hiyoshi Taisha as protector of the temple was given high imperial status, and in medieval times it had over 100 buildings (the temple on the other hand numbered in thousands).

My purpose on this occasion was not Hiyoshi Shrine, however, but a tour of the impressive temple buildings. In amongst the scattered halls (grouped into three main complexes) I came across several small shrines. One of them stands right on the way to the main building, the awe-inspiring Konponchudo, and is dedicated to Tenjin. As a seminary Enryaku-ji is scholastically oriented (its Lecture Hall is given prime importance), so I presume there’s a link in the educational role of Tenjin.

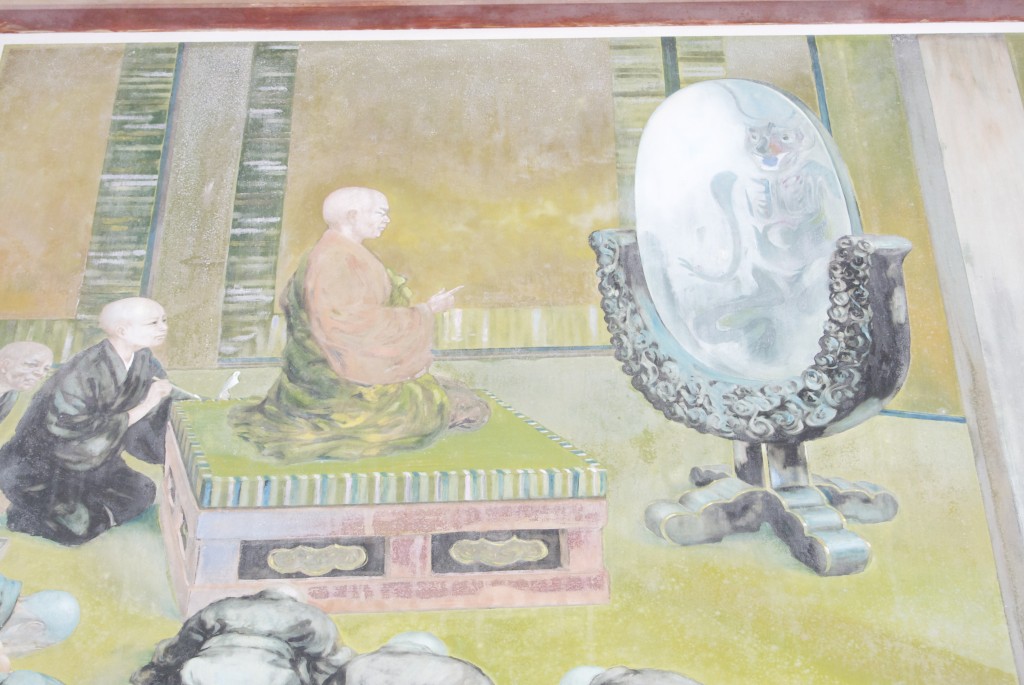

The demon seen by Gansan Daishi, now put on ofuda to be placed on door entrances to scare away evil

Amongst the other shrines I noticed was one to Inari and several to Benzaiten. The latter derives originally from India, and as a Hindu goddess she was embraced by early Buddhism, so perhaps it’s no surprise to find her well represented. I’m used to seeing her surrounded by water (as in the famous Benten pond at Todai-ji), but I couldn’t in these cases find any evidence of a pond. So why were the monks so keen on cultivating her, I wondered…

It was one of several questions I wanted to discuss, but on this occasion I didn’t get a chance. I did however get to talk to an apprentice, who told me an interesting tale about the altar mirror at the temple to which he was attached. Shaped like a Shinto mirror, it was associated with a monk called Gansan Daishi who lived at a time when the plague was prevalent.

When he looked into the mirror, Ganshin saw a demon there and his companions managed to ‘capture the reflection’ by drawing its image. When the picture was put on the front door of houses, it turned out to have a miraculous protective power against the plague. The demon was thus able to serve as a valuable assistant to the work of the monks. It’s a reminder of how Japanese demons (oni) should not be ‘demonised’ – the ascetic En no Gyoja, for instance, was served by two ‘demon’ assistants. It also says something about the curious nature of mirrors – though quite what is something on which I’ll have to reflect!

A painting of Gansan Daishi looking in the mirror and seeing a demon

A shrine to Benzaiten in the Yokowa area of Enryaku-ji. This one did have a pond, full of irises.

Inari Shrine in the woods... living close to nature, the Enryaku-ji monks have a fine sense of the spirit of place.

Another Benzaiten shrine, this one opening onto the slopes where the Buddhist monks practise their austerity rites