Islands are one of Japan’s greatest assets. These little microcosms dotted around the mainlands offer idlyllic escape from the rat race and transport the visitor to an earlier age of timeless traditions. The Shinto practised here is unencumbered by the machinations of mainstream politics, and the faith in animist and ancestral spirits finds outlet in sake´and celebration. Like the fresh sea air, it is pure and invigorating.

The Japan Times recently carried an article on the Oki Islands, which lie off the Shimane coast in the Japan Sea. There are 180 islands in all, though only four are inhabited. I’ve long wanted to visit them, and any excuse to reconnect with the haunting Matsue area has to be welcome. After reading the article, I’ve moved the islands up my list of priorities.

In the extract below can be sensed the appeal of Japan’s traditional spirituality, with shrines that speak to safety at sea and gratitude for the bounty of its produce. (For the full article, click here.)

For a longer, detailed account of shrines on the Oki Islands, see Joseph Cali’s excellent blog on the Shinto Shrines of Japan.

*************************************************************

Nishinoshima coastline (photo by Angeles Marin)

BY STEVE JOHN POWELL

The next day, exploring the small town, we were intrigued by the ubiquitous sight of what looked like white socks spinning round on small motorized clothes-driers. Closer inspection revealed that the “socks” were squid torsos, gutted and impeccably cleaned. Squid are a major concern in the Oki Islands, where fishing and tourism are about the only money-spinners.

Then later, at the end of one tiny inlet, we stumbled across small but beautiful Yurahime Shrine, dedicated to the guardian deity of the sea and said to have been founded in 842. And as if they sense its spirituality, sometimes in winter so many little cephalopods throng the adjacent Ikayosenohama (Squid-calling Harbor) that, the priest assured us, you can catch them with your hands.

However, our main challenge that day was to find mysterious Takuhi (Burning Fire) Shrine, hidden away near the island’s highest point. The helpful lady at the little tourist office recommended us to hop a bus as far as it went, then booked us a taxi to take us from the bus stop to the foot of the mountain.

The countryside was delightful: Narrow roads wound round soft green hillsides dotted with mossy shrines and cattle with oddly twisted horns grazed on the slopes while black butterflies the size of bats flopped around like lovesick fedoras.

When the asphalt ran out and a steep overgrown path began, the taxi driver stopped. He instructed us to help ourselves to a stout stick from a box by the path.

“Walking sticks?” I asked.

“To ward off snakes,” he explained, gesturing that we should beat the undergrowth as we walked.

The constant chirping of cicadas revved up to an intimidating roar as we beat our way up the narrow path through thick dank vegetation. But the tree cover gave us welcome shelter from the sun’s midday ferocity. Occasional clearings offered stunning views of the shimmering golden sea, with mist-shrouded islands stretching away like a dragon’s tail.

Fortunately, the mountain’s summit is at a none-too-lofty 450 meters, and before long we were confronted by a magnificent 800-year-old cedar that stands before the shrine up there — a building every bit as impressive as we’d been promised. Built out from a huge cave in the mountainside in the mid-Heian Period (794-1185), so that it’s half inside it and half in the open, the astounding structure looks as if its builders just gave up and left it there.

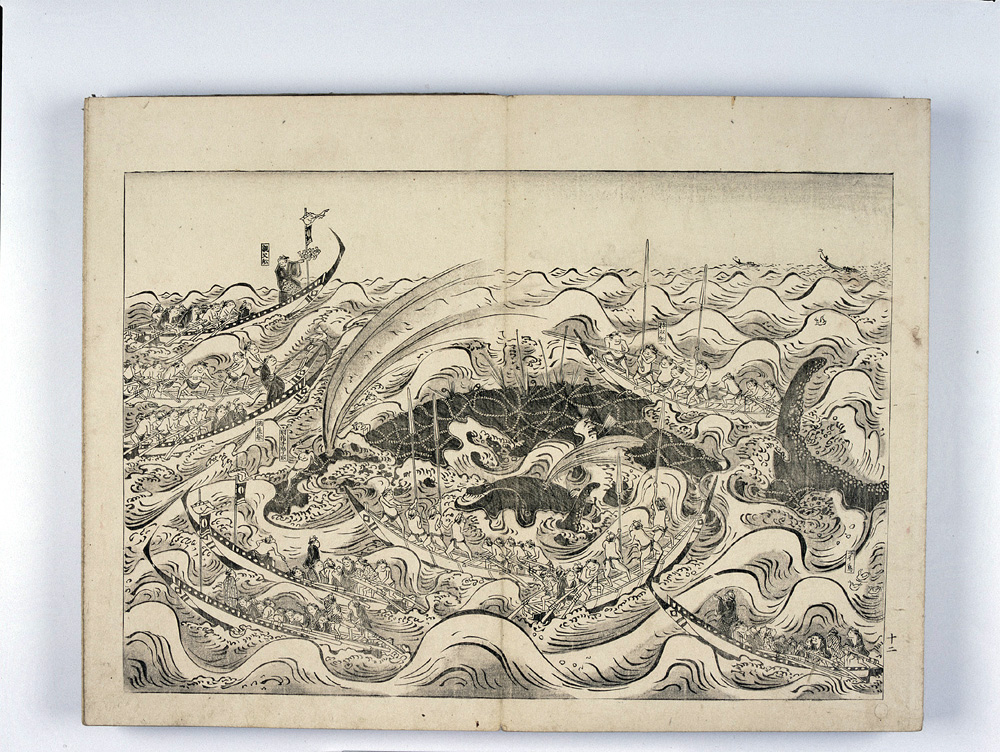

Like Yurahime, Takuhi is dedicated to the sea-guardian deity. In olden times, islanders used to light a beacon outside it to guide boats into the bay in bad weather — hence it’s called either the Burning Fire or Torch shrine. Hiroshige made a woodcut print of the scene, and boats still sound their horns when they come in sight of this shrine.

Before leaving Nishinoshima, we returned to the Kuniga cliffs, this time to see them from above. A regular bus service took us from the port to the wide-open spaces of the clifftops, with their delicious breezes and lush pastures. Up there, it felt a world away from the humid claustrophobia of Takuhi’s snake-and-mozzie kingdom. The cliff-top trail has been voted one of Japan’s Best 100 Hikes.

Cows and horses rule these heights. They love to prove the point by resolutely dozing in the middle of the road, holding up traffic as if in sit-down protest. Atop the cliffs in blissful satori, we watched entranced as wraithlike wisps of mist streamed over the rocky coves below.

For our fourth and final day, we took a short ferry ride over to Nakanoshima, more commonly known as Ama, where we arrived at midday to find the town buzzing in anticipation of the evening’s matsuri (festival). The cool of evening brought a colorful parade, spurred on by mighty taiko drums and the consumption of much beer and sake — along with lashings of scrumptious festival food: takoyaki (octopus balls), baked sweet potatoes, dumplings, taiyaki (fish-shaped buns) and, of course, heaps of skewered roast squid. After a few days communing with the mountain gods, it was a cheery welcome back to the world.

Following a stellar fireworks display, launched from a floating platform out in the bay, a free bus was laid on to take everyone home. We were debouched in the middle of nowhere in utter darkness, but the jolly island ladies who packed the bus assured us that our minshuku, booked for us by the tourist office in Ama port, was just a few yards down the road. They were right.

Next morning we awoke early and strolled round Oki Shrine, which was handily just across the road. The priest arrived in his white tunic and baggy purple pants and told us the story of how the emperors Go-Toba (1180-1239) and Go-Daigo (1288-1339) were banished to these islands. I suppose exile is always a bit ignominious, especially when you’ve been brought up as a demigod. But, gazing around at the forested hillsides glistening in the soft morning sunshine, I couldn’t help feeling that, as banishings go, this really wouldn’t have been such a terrible punishment.

Ferries to the Oki Islands leave from Matsue and Shichirui in Shimane Prefecture and Yonago and Sakaiminato in Tottori Prefecture. There are daily JAL flights from Osaka Itami Airport to the largest island, Dogo.

Kayaking into a different dimension (courtesy visitshaimane.com)

The Japanese have long made a cult of cherry blossom. It used to be plum blossom until Heian times, a custom adopted from China, for the reawakening of nature after the long sleep of winter was marked by the miraculous first flowering of the fruit tree. But the Japanese preference for cherry gradually prevailed, driven by an affinity with the evanescence of its blossom.

The Japanese have long made a cult of cherry blossom. It used to be plum blossom until Heian times, a custom adopted from China, for the reawakening of nature after the long sleep of winter was marked by the miraculous first flowering of the fruit tree. But the Japanese preference for cherry gradually prevailed, driven by an affinity with the evanescence of its blossom.