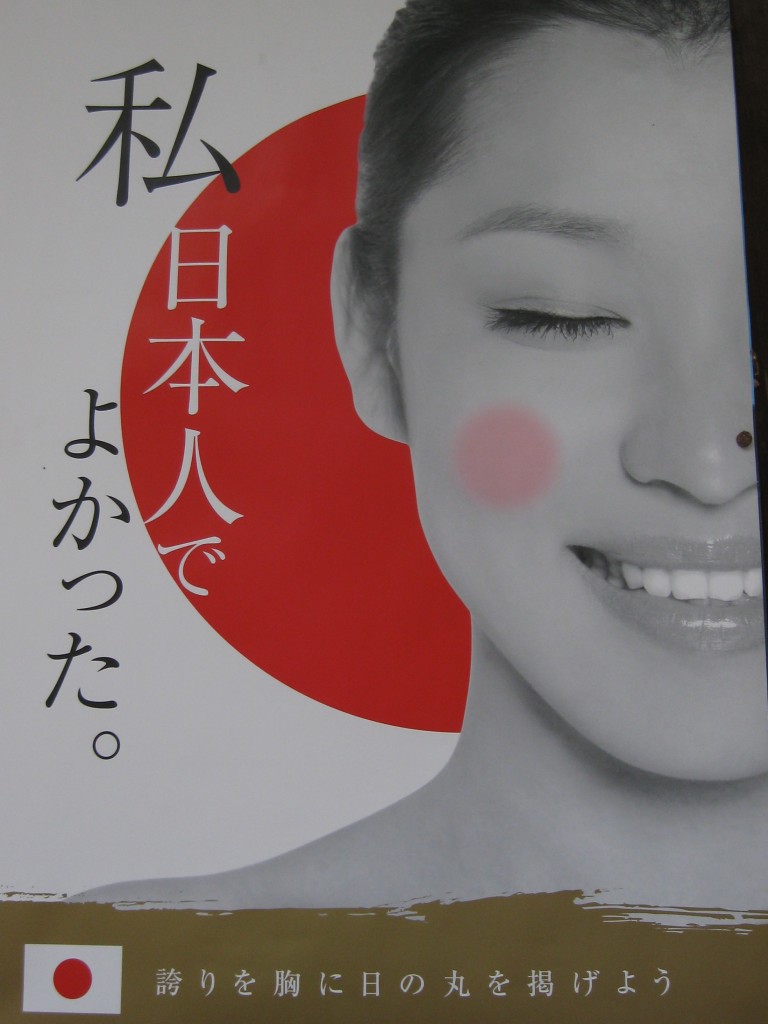

Priest in the elegant surrounds of Kasuga Taisha

Kasuga Taisha is one of Japan’s foremost shrines. It is associated with the Fujiwara family, once the most powerful in the land, and is famous for its setting on the edge of Nara Park where it is surrounded by a primeval forest at the foot of two sacred hills. (Both shrine and the forest are part of the World Heritage listing of the ‘Historic Monuments of Ancient Nara’.)

According to legend, the Fujiwara invited a powerful deity to Nara who arrived riding a white deer, which is why the animal is regarded as sacred and allowed to wander at will around the grounds. Three other kami are enshrined, one of them being the founding ancestor of the Fujiwara. For centuries the family were able to marry their daughters to prospective emperors, so that even after the capital at Nara was abandoned in 784 Kasuga survived thanks to imperial patronage.

A deer grazes in the main compound, in a form of nature worship, with some of the 1000 bronze lanterns at the shrine

In the late Heian Period (794-1185) the shrine came under the auspices of Kofuku-ji, the Fujiwara family temple. The powerful Shinto-Buddhist complex (175 structures at its height) only came to an end following the Meiji Restoration of 1868 when the new government separated the two religions. Until then Kasuga maintained the shikinen sengu tradition of rebuilding every 20 years, in keeping with the notion of renewal that lies at the heart of Shinto.

The approach to Kasuga is lined with lanterns, donated in the past by worshippers of all classes. Lighting a lantern was the customary way to greet the spirits of the dead, and there are 2000 stone lanterns in all, some of which are so tall that they dwarf their human admirers. There are a further 1000 bronze lanterns hanging at the shrine, so that the total matches the 3000 Kasuga branch shrines throughout the country. When all of them are lit, which happens twice a year, the effect is spectacular.

Inside the shrine is a chumon gate dating from 1613, to the left of which is a Japanese cedar estimated to be eight hundred years old. The main compound with its vermilion pillars houses four sanctuaries, one for each of the kami enshrined. They are in the kasuga-zukuri style featuring a canopied entrance beneath a gabled roof, which is thought to have originated in the eighth century and which became a model for other shrines.

The cypress-bark roof harmonises with the surrounds, exemplifying the Shinto thinking that humans are an integral part of nature. The woods here have been sacred since 841, when hunting and tree-felling were prohibited, and the only human intervention apart from reforestation after typhoon damage is in the form of footpaths, one of which leads up the hill past stone statues and waterfalls.

Near the shrine are a number of other attractions. One is the nearby Wakamiya Shrine, an auxiliary shrine founded in 1135 which is famous for its Onmatsuri traditional dance festival. Opposite stands the Meoto Daikokusha, an enmusubi shrine where a pair of married deities bring good luck in match-making. Kasuga also owns a Treasure Hall containing precious items, many of which were imperial offerings in the Heian Period – items such as mirrors, masks, furnishings, calligraphy, decorated weaponry and musical instruments.

Near the Treasure Hall is a Botanical Garden featuring 250 plants from the Nara Period, as well as a section containing 200 wisteria trees of 20 different types (the tree is a shrine symbol since Fujiwara translates as ‘field of wisteria’). Next to the garden is the Nintai tea room, built in the eighteenth century, which serves a ‘Manyo porridge’ eaten in the Nara Period. In this way the shrine and its surrounds offer the perfect opportunity to eat, breathe and soak in the atmosphere of the eighth century when Heijo-kyo (Nara) was the country’s capital and Japanese culture as we know it was being shaped.

*****************************************

For more about the shrine, see p.161 of Shinto Shrines (Univ. of Hawaii Press)

Shrine overview, with the chumon gate built in 1613 connected to the surrounding corridor

Deer and stone lanterns - two of Kasuga's motifs