Priest Volkhvy in the honden of the minzoku neo-Shinto shrine

Why and how did you come to formulate something called “minzoku NEO-shintô”?

When asked to define my spiritually, I usually call myself a poly-affined poly atheist. Poly-affined means maintaining membership in multiple communities, and poly-atheist means not “believing” in a lot of gods; or rather while acknowledging their existence, not assigning them the status of “god” (at least not in the Western sense of the word).

I’ve been exploring various alternative religions and philosophies for over 45 years now. The ones that attracted me most were the “folk religions”; that is the common peoples’ expression of a particular religion. These are not religions as they’re practiced in temples and shrines, or taught in theological seminaries or academic universities. Instead they are the religious practices that the common people of a culture engage in to help get them through the day.

The honden as seen from the outside

The more I learned, the more I saw that these folk religions had much in common with each other. The cultural forms are different, but the reasons behind the actions are shared. People everywhere, being people, have the same needs and engage in similar practices to fulfil those needs. This being the case, I wondered if it was possible to integrate the practices of my many communities in way that would be acceptable to each community. “Minzoku NEO-shintô” is one attempt to achieve that goal.

There are several reasons why minzoku shintô (folk Shinto) was chosen for the framework.

* First, minzoku shintô is unabashedly syncretic. It readily borrows from other sources, both Eastern and Western. This syncretism allows for the merging with other folk religion practices.

* Second, it’s truly polytheistic, crossing boundries between disparate religious systems. It has a very pragmatic outlook that declares, “if it works, it’s true”.

* Third it’s animistic — and that’s not animistic in the ‘how primitive’ sense. Rather it’s animism in the sense of imbuing our view of the world with a sense of wonder, mystery, and awe. Much of what many modern groups are trying to do is re-enchant a worldview turned coldly mechanistic, and relearn how to live in a world that’s alive.

* Fourth, because it’s based on folk practices, it can be practised anywhere; it doesn’t need an “official” priest or a shrine, just an interested lay person. A shrine or priest are nice to have access to, but realistically for most of those who live outside of Japan neither are readily available.

* Fifth, it is very local specific. What is practiced in one location, can vary greatly from the practices in a nearby location; each location has its own unique set of practices.

* Finally, Shinto has the extremely useful concept: kami — that which inspires feelings of reverence, awe, gratitude, fear/terror. A word that encapsulates a number of related ideas. That they’re everywhere and in everything. That we are not alone, they’re our neighbors and we share the world with them. That we are all interdependent and need to respect one another.

Could you tell us about the ‘shi-yaku-jin no hokora‘ and the kami involved?

the shi-yaku-jin shrine

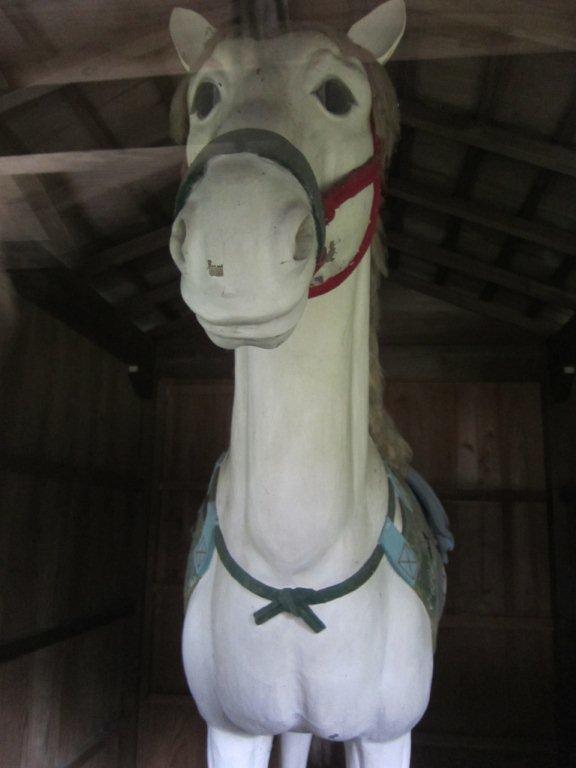

The shi-yaku-jin no hokora is a small family owned shrine. It is called a hokora as the person who maintains it, its kannushi (priest), is a layperson and not a professional Shinto priest. It occupies two rooms on the top floor of the family home. As a response to the current recession, it was established on November 1, 2010 to calm the shi-yaku-jin — the four misfortune kami — and mitigate their effects on eastern Minnesota and northwestern Wisconsin.

There are seven kami enshrined within the hokora. Baba Yaga, hi-no-kami, and tsuki-no-kami are charged with the task of watching over and prevailing on the shi-yaku-jin — binbô-no-kami (kami of poverty), ekibyô-no-kami (kami of epidemic disease), kyô-no-kami (kami of disaster and famine), and shi-no-kami (kami of death) — to moderate their effects upon the Twin Cities Metropolitan Area.

The “names” of the enshrined kami were deliberately chosen to indicate that they are autochthonous kami — in fact in minzoku NEO-shintô, as practiced locally, names that can be tied to locations within Japan are generally avoided. The “honden” (sanctuary) also contains the family ancestor altar and a butsudan (Buddhist altar). The rooms occupied by the hokora are currently in the process of being renovated. Unfortunately, more than likely because of the presence of binbô-no-kami, the renovation is taking much longer than originally planned.

What is your relationship to other groups in the region?

Twin Cities Pagan Pride

The hokora tends the Memorial Ancestor Shrine for the local Neo-Pagan comunity. It maintains cordial relations with the Sacred Cedar Shrine, the Minnesota Heathens community, TwinCities Pagan Pride, Iowa Pagan Pride, Greater Chicagoland Pagan Pride, and several other local groups that sponsor meetings and Pagan festivals in the area.

How long have the projects been going, and what kind of reaction have you got (including from Japanese)?

Although I have been interested in Shinto for many years, it wasn’t until mid 2009 that I started seriously researching it, and subsequently started writing minzoku NEO-shintô: A Book of Small Traditions in early 2010. I gave the first public presentation on minzoku shintô in September 2010 at an event sponsored by Twin Cities Pagan Pride. Encouraged by the response, I established the shi-yaku-jin no hokora on November 1, 2010 and launched the companion website in December 2010.

It’s difficult to judge the reaction of the Japanese as most of the feedback received so far is from America and is not usually identified as being from a person of Japanese descent. That said, I have yet to receive any negative feedback. After public presentations, I have been told by several of people that they were pleasantly surprised that there were active practitioners of Shinto in the Midwest. I have also received encouragement and support from a number of local Neo-Pagan leaders. Even though it is family owned, the hokora has fifteen, for lack of a better word, ujiko (parishioners) who are willing to share the shinsen (offerings), despite knowing which kami are enshrined there.

What rituals and activities are performed?

The hokora is tended daily during which each of the gosaijin (enshrined kami) are invited to attend, offered norito and other forms of entertainment, and any special kigan (prayers) are made. Full shinsen are made twice weekly to the kami, the ancestors, and the butsu (Buddhas). ‘Ooharae for hokora ujiko’ (purification for parishioners) is performed on June 30th and December 31; at these times the hokora is thoroughly cleaned.

Carrying out one of the annual rituals at the shrine

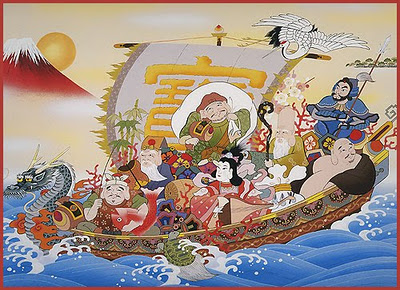

Throughout the year the hokora also performs rituals for:

shôgatsu

Koliada (Slavic midwinter feast)

shimeyaki shinji (fire ritual)

higan / shunbun no hi (vernal equinox)

geshisai (midsummer)

Kupalo (Slavic midsummer feast)

higan / shûbun no hi (autumnal equinox)

obon

Samhain ritual

tôjisai (midwinter)

oomisoka (New Year’s Eve)

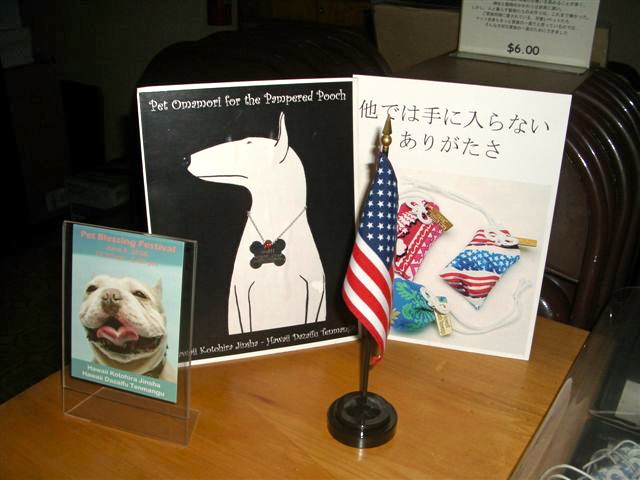

In addition, the hokora offers: ofuda (talisman), omamori (amulet), omikuji (fortune slips), and ema (votive tablets).

Then there are the daily “little traditions”: misogi (cold water austery) in the shower and at the sink, praying at the family ancestor altar, making offerings to the Domovik and the Domovika (Slavic domestic spirits), saying itadakimasu (for what we are about to receive) and gochisô-sama deshita (thank you for what we received) at meals; chanting rokkonshôjô (purifying the six senses) for self-purification; bowing and clapping in front of the altars; and using honorifics and polite forms of address.

What plans do you have for the future?

First and foremost, continue tending the hokora. It’s a bit like grabbing a tiger by the tail — once you grab hold, it suddenly seems like a really bad idea to let go. As a result, one of the top priorities is to find a successor to act as kannushi to the hokora. The hokora has someone willing to be a miko, so a training regimen needs to be developed for her. Work on expanding minzoku NEO-shintô: A Book of Little Traditions and continue fostering an active “minzoku NEO-shintô community” in the Midwest. Hopefully in the future the hokora will be in a position to sponsor an annual matsuri (festival) on its founding date.

***************************************************************************************

The shi-yaku-jin hokora has a participatory virtual shrine where visitors can wash their hands, ring a bell, pick their fortune and purchase goods. Click here.

***************************************************************************************

The Memorial Ancestor Shrine

the shi-yaku-jin hokora, shrine of the minzoku neo-shinto