Torii – entrance to a sacred world

The origins of the torii are something this blog has explored before, noting the Korean connections and the possibility that tori-i (bird’s roost) may have served as a perch for chickens and roosters at the gateway to villages. Roosters are special in Shinto because they wake up the sun in the morning, and in the famous Rock Cave myth they wake up the Sun Goddess herself.

Now a long article on torii origins has been published on the fascinating Japanese Mythology website. The website declares its purpose as ‘to map the mythologies of Japan and to back-track the trails of their origins outside of Japan.’ It’s a refreshingly broad and international approach to what can often be stiflingly insular.

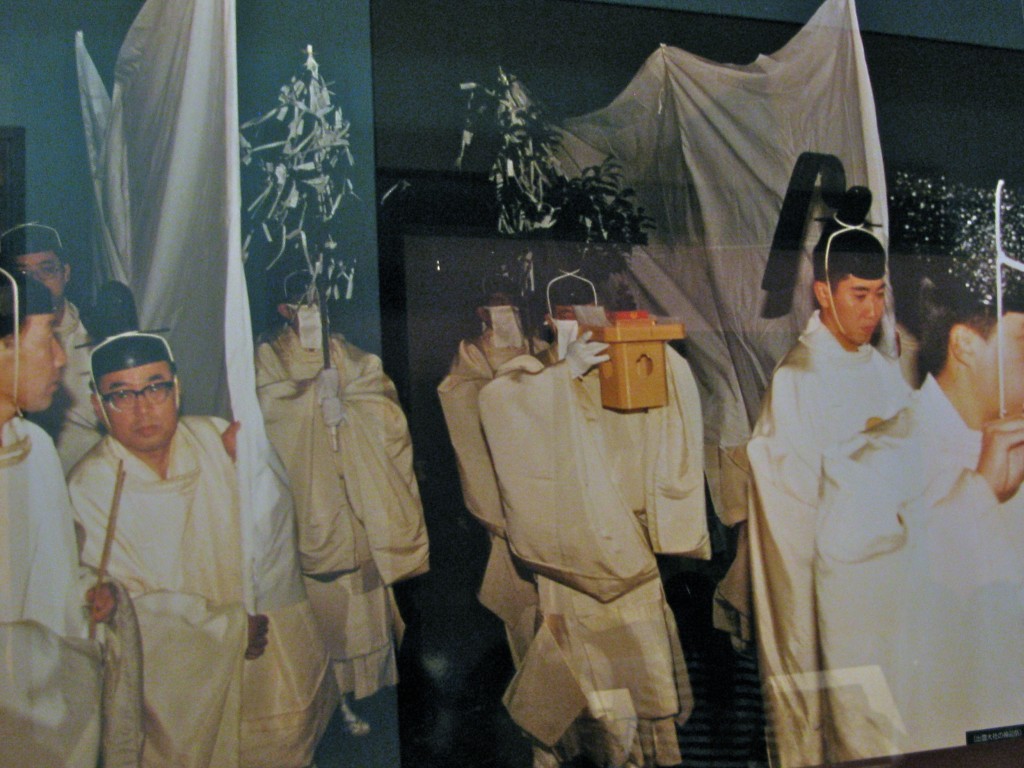

Mikoshi with phoenix on top being borne in a festival at Hakone Jinja

One possibility the article explores is the notion that the bird in question is not the rooster, but the phoenix. Strange one might think, ’till one realises that the phoenix sits on top of the mikoshi which bears kami in parades. Intriguing… it is after all a symbol of renewal, and renewal lies at the very heart of Shinto.

Moreover, it’s associated with fire, and fire is the very essence of the sun. ‘To the Japanese the Phoenix is a Talisman for Rectitude…. and they consider it a manifestation of the Sun,’ wrote William Thomas and Kate Pavitt in1922 (The Book of Talismans, Amulets and Zodiacal Gems).

The Japanese Mythology website traces the phoenix gate connection back to Persia, or to Indo-Iranic influences spread by Saka migrants. Photos show evidence of the trail of symbolic gates across Asia from India up to Korea, from where they may have spread to Japan. There’s even analysis of blood groups to back up the possibility of immigrants into Japan bringing such customs with them….

It may be that early forms of the eruv doorpost emerged from and were carried by an extremely ancient migratory lineage of Semitic-Arab origin who are represented by haplogroup D-bearing (Y-DNA) ethnic population groups including the Druzes, the Kalash(pre-Vedic culture of Pamir-Hindu Kush mountains), the Sindhi of Pakistan, etc. (see the map of the haplogroup D trail) who eventually reached Japan during the Kofun Period in substantial numbers as bearers of pre-Vedic rituals and horse and sacrificial culture with them.

Gate before a Korean burial mound in Seoul

Most fascinating of all, to me personally, is the notion that the sixth-century Japanese capital at Asuka may derive its name from the Persian for ‘Ark Saca’ or sacred place of the Saccas (Scythians).

It’s noted too that the written characters used for Asuka – 飛鳥 – mean ‘flying bird’. Flying bird?!! For shamanic cultures flying birds were emissaries from on high, acting as the intermediaries between earth and heaven. Is this linked to the introduction of the torii in Japan, and if so which sacred bird would it be referring to?

The Japanese Mythology site has its own suggestion, deriving from the area around the Indian subcontinent. But while travelling through Manchuria, I came across bird representations associated with shamanism that led me to suppose they may well be linked with or been imported into Japan. It’s surely no coincidence that the emperor of Japan has a bird-shaped walking stick, not unlike the bird-surmounted pillar that stood in the Manchurian emperor’s palace.

Whatever the truth about its origins, the torii like other components in Shinto clearly shares a common heritage with East Asia. There’s nothing unique about it, but there is something deeply appealing about it.

Gate at Yoshinogari Yayoi site in Kyushu acting as bird perch (tori-i)

A model of how Yayoi-era rituals may have looked in Himiko’s time during the third century

The most famous torii in the world? Itsukushima Shrine set in the Inland Sea