A deserted bay at Chichijima in Ogasawara, one of only two inhabited islands amongst the 30 or so in the archipelago

There can’t be many blog entries about Shinto in Ogasawara (aka the Bonin Islands)!

One reason would be their remoteness (25 hours by ship from Tokyo). Another would be their size (2 inhabited islands with a population of 2500). But the most telling reason of all would be that they were uninhabited until relatively recently – the 1830s – and even then they were settled by Westerners. It was not till the 1860s that the islands were claimed by Japan, and only afterwards did the setting up of shrines become a possibility.

Such is the curious history of the islands that descendants of the original American sailors remain to this day. Nathaniel Savory was their leader, and his descendants are now known as Saberi – they even have kanji for their name, which they were forced to adopt in World War Two. The descendants of a sailor called Washington made things easier for themselves. They changed the family name to Kimura.

One of several plants on Ogasawara that are endemic to the islands

What were the American sailors doing there in the first place? Well, they belonged to a founding group of over 20 people, some of whom were Europeans and several of whom were Polynesian ‘wives’. They were an outpost for the whaling expeditions being mounted in the Pacific, to provide fresh supplies. The group of 30 or so islands lay about 1000 kilometers south of Edo and were uninhabited.

A British ship called by at one stage and left them a Union Jack, hoping to claim them for the Empire. Some time later, in 1853, Admiral Perry came to visit and instructed the ragamuffins on how to form themselves in American fashion. As leader he appointed a sailor from Hawaii. It led to a spat between the UK and the US over ownership.

The group had settled on an island now called Chichijima, but at some stage an English sailor called James Motley took it upon himself to move to a neighbouring island, now known as Hahajima, with his wife Ketty. There they were joined by a German called Rolfs, originally from Bremen. When Motley died, Rohlfs married his widow – conveniently since there was no one else available on the island.

Things came to a head in 1861 when the Japanese government in Edo decided to establish their rule and sent an expeditionary force, but it was not until the 1870s that the islands were officially integrated into Japan. The Euro-Americans were allowed to remain, but Japanese settlers were brought in from Hachijo-jima. The mixed community survived by farming and fishing, until WW2 when the fighting in the Pacific forced evacuation of the islanders to Tokyo. (Iwo Jima lies not far away.)

After the US conquered the islands, they occupied them until 1968, when they were handed back to Japan. Some of the islanders returned, but only a small percentage. They have since been joined by others, looking to start a new life. Now descendants of the original inhabitants are few, and it’s said that 80 percent of the population are ‘newcomers’.

Shrines

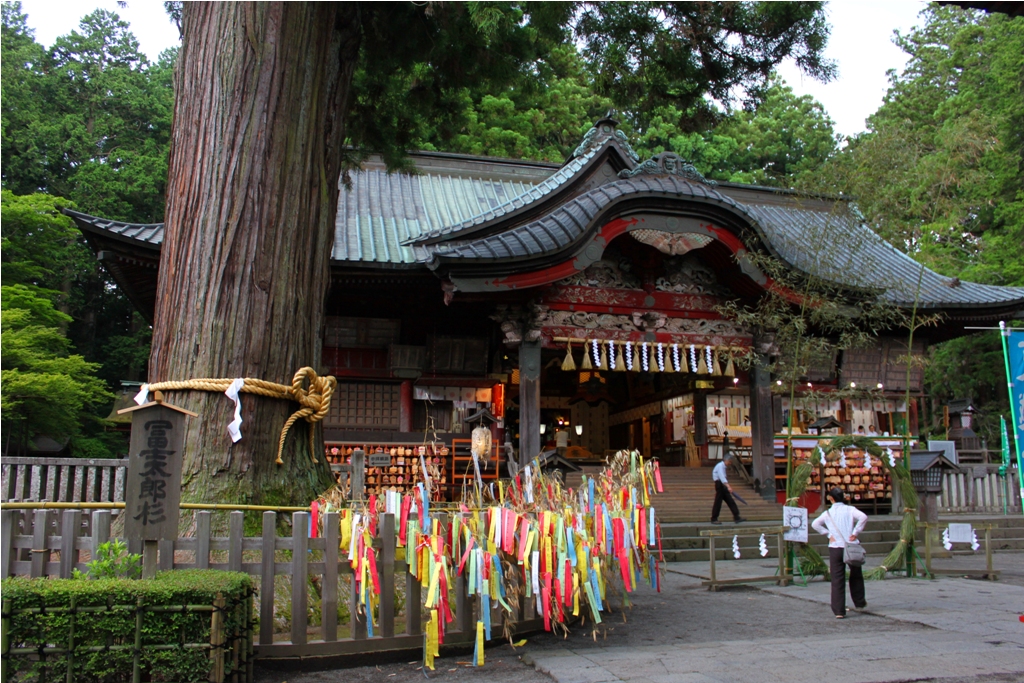

Ogasawara Shrine, which honours the putative discoverer of the islands as kami

Of the two shrines on Chichijima, one is dedicated to the supposed discoverer of the islands, a samurai called Ogasawara who according to tradition came upon the islands in 1597. (No one seems certain if this is true or just a legend.) Usually a founder-ancestor is honoured by a splendid shrine, but there was a desultory atmosphere with some ugly sheds nearby. But at least there was a view of the sea for the one-time mariner.

More impressive is the island’s main shrine, called Ogamiyama. It honours Amaterasu as well as the Kumano and Kasuga kami, and stands on a hill in front of the island’s harbour, with 125 steps leading up to it. There were two note-worthy features: one was that the wash-basin had a sliding panel in order to keep birds from washing themselves in the water. The other was that the shrine sported a sumo ring. Here on this Pacific Island, with its small population, the mainland tradition of wrestling for the pleasure of the kami is carefully cultivated.

The wash-basin shielded by a box with sliding panel to keep away birds that want to purify themselves

The sumo ring with seating behind, where the island's young men display their robustness to the kami

The Ogamiyama Jinja, main shrine on Chichijima Island

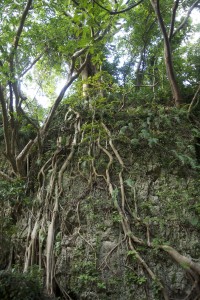

On the smaller island of Hahajima, the Tsukigaoka Shrine stands on a small but steep incline in front of he port. The building itself is nothing special, but behind it is a most wonderfully atmospheric area of gnarled trees and strangely shaped rocks. The path leading through it is overgrown and apparently little used, but the early settlers of the island must surely have sensed here something of the fecund spirit of the island.

The shrine at Hahajima. Notice the buddhist-style bell hanging from the tree.

Part of the atmospheric surrounds behind the shrine

World Heritage

Last year the Ogasawara islands were made a World Heritage Site because of the unique nature of the environment. While the rest of Japan was once joined to the Asian continent, Ogasawara was not. It led to a distinctive evolution for its flora and fauna, and the islands have been nicknamed ‘the Galapagos of the East’.

There are several trees and flowers endemic to the island, while on a night tour I got to see the Bonin bat as well as a unique type of fluorescent mushroom. The early settlers introduced animals and plants that have proved destructive of the natural environment; wild goats for instance eat endangered species, and feral cats have hunted a rare type of pigeon almost to extinction. As a result there are measures to remove the outside species and to prevent seeds and spores being brought in from elsewhere. Tourism is limited, with no airport and the only means of access the Ogasawara maru out of Tokyo.

The intention now is to preserve the environment of the past for future generations. In this way the spirit of place honoured by the Shinto shrines finds harmony with the Unesco programme of preservation. Long live Ogasawara! With their clear blue seas, coral reefs, thickly wooded hills and unspoilt nature, these are islands to savour and treasure.

Coastal view on the sparsely populated Hahajima

A turtle enjoys the clear waters around the islands

The vegetation on the islands is lush and in many cases unique

The distinctive Octopus Tree (tako no ki), named after the many 'legs' it has

Well, there’s a lot more that can be said about the shrine. In fact, I did myself in a previous blog entry! (click

Well, there’s a lot more that can be said about the shrine. In fact, I did myself in a previous blog entry! (click

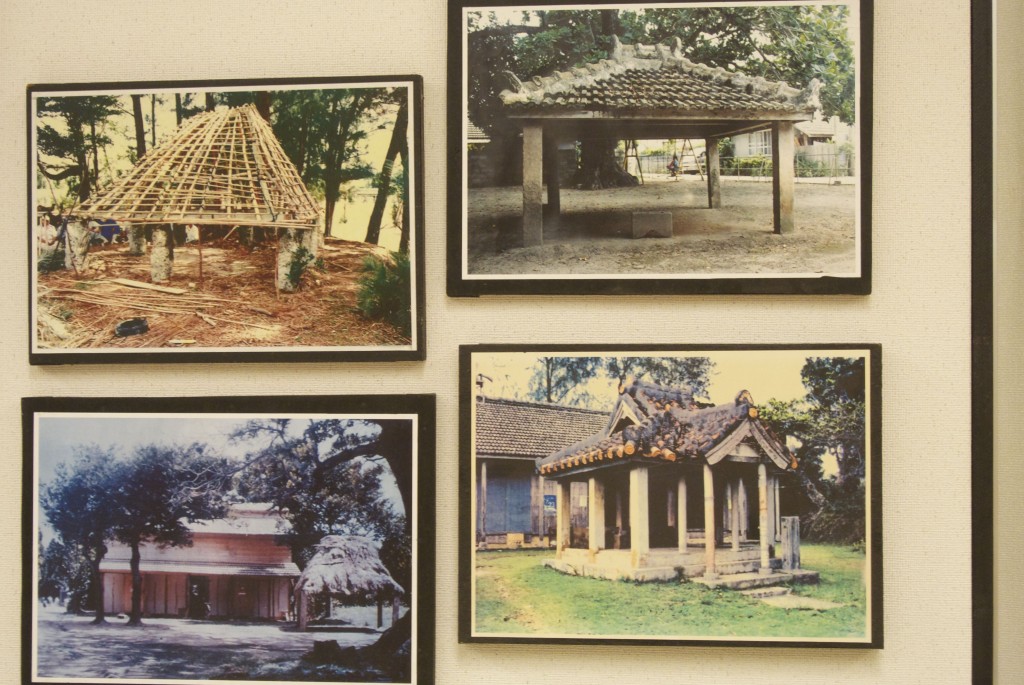

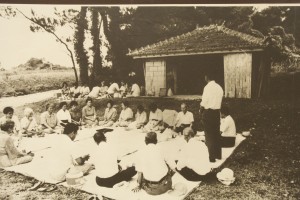

The kamiasagi on the other hand were not hallowed ground as such, but places where gatherings could be held. Since they were easily accessible by villagers, they acted as an intermediary point between the village and the sacred site. Not every village had one, I was told, but most did.

The kamiasagi on the other hand were not hallowed ground as such, but places where gatherings could be held. Since they were easily accessible by villagers, they acted as an intermediary point between the village and the sacred site. Not every village had one, I was told, but most did.