Remains of Nakajin gusuku (castle)

Much of the Okinawan World Heritage registration has to do with castles dating from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. Visiting them reveals how important a role the so-called ‘Ryukyu religion’ played, for sacred sites and altars abound. These were clearly a religious people, and as elsewhere in East Asia their religion combined ancestral worship with animism.

Spiritual authority was delegated to females, who were responsible in a literal as well as symbolic way for keeping the home fires burning. Traditionally it was the woman’s job to look after the household gods and ancestral spirits, as well as to pray for the well-being of the family’s males when they were away at sea or at war. During the time of the Ryukyu kingdom, the arrangement was systematised with a hierarchy of female priests to pray for the well-being of the nation and the king.

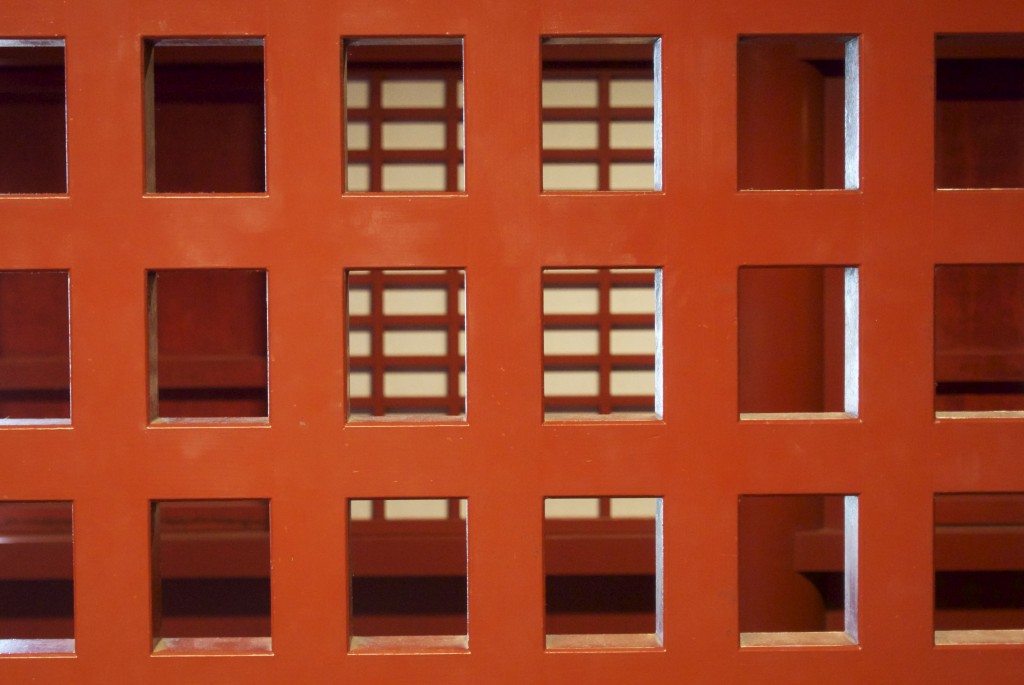

At Shuri Castle the outer courtyard features a utaki (sacred site) housing a sacred tree, while inside the palace is a space reserved for religious rites. Outside the palace is a gate which was never opened, for behind it stood a grove inhabited by spirits. Before departing, the king would stop and pray before it, while on his return he would give thanks for his safety.

Shuri Castle utaki (sacred site)

Sonohiyaun stone gate, which never opened

Space reserved for rites in Shuri Palace

Other castles too had their sacred sites, and I was lucky enough to catch a brief ceremony at one carried out by a local noro (priestess). It was at Nakijin Castle, a ruined castle in the north of the main island. First the group of four women honoured the Hinukan, fire god or god of the hearth. In terms of the wider community, the Hinukan was responsible for the social well-being. “Worship of the fire god [in Okinawa] is very old and predates worship of ancestral spirits (sorei) at the Buddhist altar, now the center of family ritual,” says the Kokugakuin encyclopedia.

As well as prayers, there were offerings of rice and incense – with one big surprise: the bunch of incense was lit with a blow-torch. Afterwards a similar ceremony was carried out at the ruins of a utaki (sacred site). Casual and done in squatting style, the ceremony reminded me of Korean shamanism, also carried out by females. It’s a reminder of how Okinawa lay at the maritime cross-roads of China, Korea, Japan and southern trade routes in times past. The resulting cultural mix produced the distinctive flowering of the Ryukyu kingdom, which was one of the chief criterion in the island’s World Heritage citation.

Ceremony in the castle ruins at the former utaki (sacred site). Notice the squatting style. The noro (priestess) conducting the ritual is in the centre of the utaki.

Two of the attendants at the Hinukan ceremony. As god of the hearth, the fire god has his own building. From what I could gather, the woman in white was the apprentice noro (priestess).

Sacred site at Nakagusuku castle ruins

Former atlar at the Nakagusuku ruins

1) What is the correct way to pass through a torii at the entrance to a shrine?

1) What is the correct way to pass through a torii at the entrance to a shrine?

The quiz was intended to prepare people for Hatsumode (New Year), and in true Japanese fashion it was all about the correct form. Belief in the kami was never mentioned or considered: it was irrelevant. Nor was the word ‘Shinto’ ever used; the ideology was irrelevant also. It was simply about how to behave correctly when you visit a shrine. Situational ethics, not faith, is the guiding principle.

The quiz was intended to prepare people for Hatsumode (New Year), and in true Japanese fashion it was all about the correct form. Belief in the kami was never mentioned or considered: it was irrelevant. Nor was the word ‘Shinto’ ever used; the ideology was irrelevant also. It was simply about how to behave correctly when you visit a shrine. Situational ethics, not faith, is the guiding principle.