The Dutch scholar Mark Teeuwen, currently professor at the University of Oslo

‘What Used to be Called Shinto’ runs the provocative title of a paper by academic Mark Teeuwen (in Japan Emerging, ed. Karl Friday, 2012). In clear and systematic fashion, he questions the notion of Shinto as ‘Japan’s indigenous religion’ by arguing that Amaterasu’s prominence not only owes itself to continental influences, but was the product of seventh-century manipulation by a usurping emperor. In these terms Amaterasu herself, and the religion which champions her, can neither be called ‘indigenous’ nor said to exhibit continuity from early times.

After emphasising Japan’s ancient links with the Korean peninsula, Teeuwen points out the diversity of pre-Buddhist Japan, rendering the idea of a single belief system ‘unthinkable’. He also demonstrates the unreliable nature of the mythology in the Kojiki (712) and Nihon shoki (720). One example is the famous story of tenson korin (descent from heaven), when Amaterasu sends off her grandson to rule over earth. In the Nihon shoki, it’s Takami-musubi, Ninigi’s maternal grandfather, who performs this function.

The opening of the rock door covering the cave in which Amaterasu hides herself. Following this, she largely fades from the mythology.

Amaterasu plays little part in the subsequent mythology, until it’s mentioned that the Yamato leader, Sujin, was troubled by the presence of two competing kami in his palace – Amaterasu and Yamato Okunitama (Great Spirit of the land of Yamato). History tells how one was eclipsed by the other, and Teeuwen ascribes this to the later championing of the sun-goddess by Emperor Tenmu (c.631-686).

The Japanese leader only came to power by beating his nephew in the Jinshin War (673), having prayed to Amaterasu for victory beforehand. Since she was associated with metalwork as well as weaving, her role in the production of weapons made her a war goddess as well as one of creativity (not unlike the Greek goddess, Athena).

A key point made by Teeuwen is that Emperor Tenmu was fostered by the Owari clan, whose ancestor was Ame no Kaguyama, in charge of mirror-making and metalwork. In the championing of Amaterasu, Tenmu could have been acting in alliance with and out of allegiance to his adopted clan. It was in his reign, and that of his widow-successor Empress Jito, that the cult of Ise was initiated, and it was under Tenmu too that orders were given for the compilation of a ‘correct’ mythology.

Rather than Shinto as such, Teeuwen suggests that the resulting collection of myths belonged to a court cult known as jingi (heavenly and earthly deities). This had nothing to do with the beliefs of ordinary folk, but was aimed at boosting the prestige of the emperor and his allies. The central idea was that the emperor as heavenly descendant of Amaterasu would patronise all the earthly kami of the realm by sending them gifts, thereby confirming his authority over them.

The final part of Teeuwen’s analysis – for me, the weakest part – is a claim that Amaterasu underwent a gender change at the time of Empress Jito. However, there is no evidence to back up the argument, which is based upon the assumption that Empress Jito needed a divine role model for her intention to pass authority onto her grandson. This goes along with Teeuwen’s assertion that the sun is ‘obviously yang and therefore male’. However, it seems unlikely yin and yang would have played a part in the personifications of nature prior to the sixth and seventh centuries. Moreover, the sun is female in many cultures, notably in Mongolian shamanism which may have played a vital part in Japan’s religious development.

There are in fact good reasons for supposing Amaterasu to be indelibly female. For one thing, she is associated with weaving, which was the preserve of aristocratic women. For another it’s known that shamaness-rulers like Himiko played a leading part in ancient Japan and were seen as imbued with magical powers. Perhaps in ancient times a miko shamaness was revered as being as radiant as the sun, not unlike Louis XIV, and with death and the passage of time she became conflated with the very sun itself.

“The Shinto view of a purely indigenous Japanese antiquity is a myth,’ concludes Teeuwen decisively. One has the feeling that he’s here trying to bury the whole Nativist notion of an ancient and purely Japanese religion in order to get on with the question that is vexing him: why did the Japanese court not copy Chinese models, but invent a ritual and mythology of its own?

This is by far the clearest account I’ve read yet of the argument in academia about whether Shinto as such existed in ancient times. It surely places Teeuwen in the very forefront of a debate which is certain to rumble on for years. This short paper (11 pages) is intellectually stimulating, refreshingly clear of jargon, and is much to be recommended.

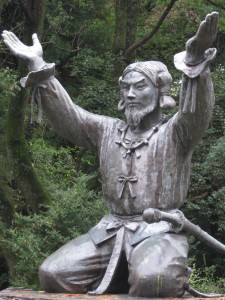

A modern image of Amaterasu. Did she undergo a gender change at some time?