July 7 is the date of the Tanabata celebration, and in the days leading up to it decorated bamboo branches can be seen around Japan. Jut over 100 years ago when Lafcadio Hearn (1850-1904) wrote fondly of the festivities. He was able to explore Old Japan just as it was modernising under the influence of the West, and he wrote in loving terms of its religious customs and festivals. Hearn was a romantic, so it is not surprising that the meeting of two lovers in the form of stars should have appealed to him so much. He wrote a lot on the subject, detailing the different practices in various regions. It provides a good example of Hearn as folklorist, one of the many guises of this remarkable author. Here are excerpts from his book The Romance of the Milky Way (1905), which give an indication of how important the event was in times past.

****************

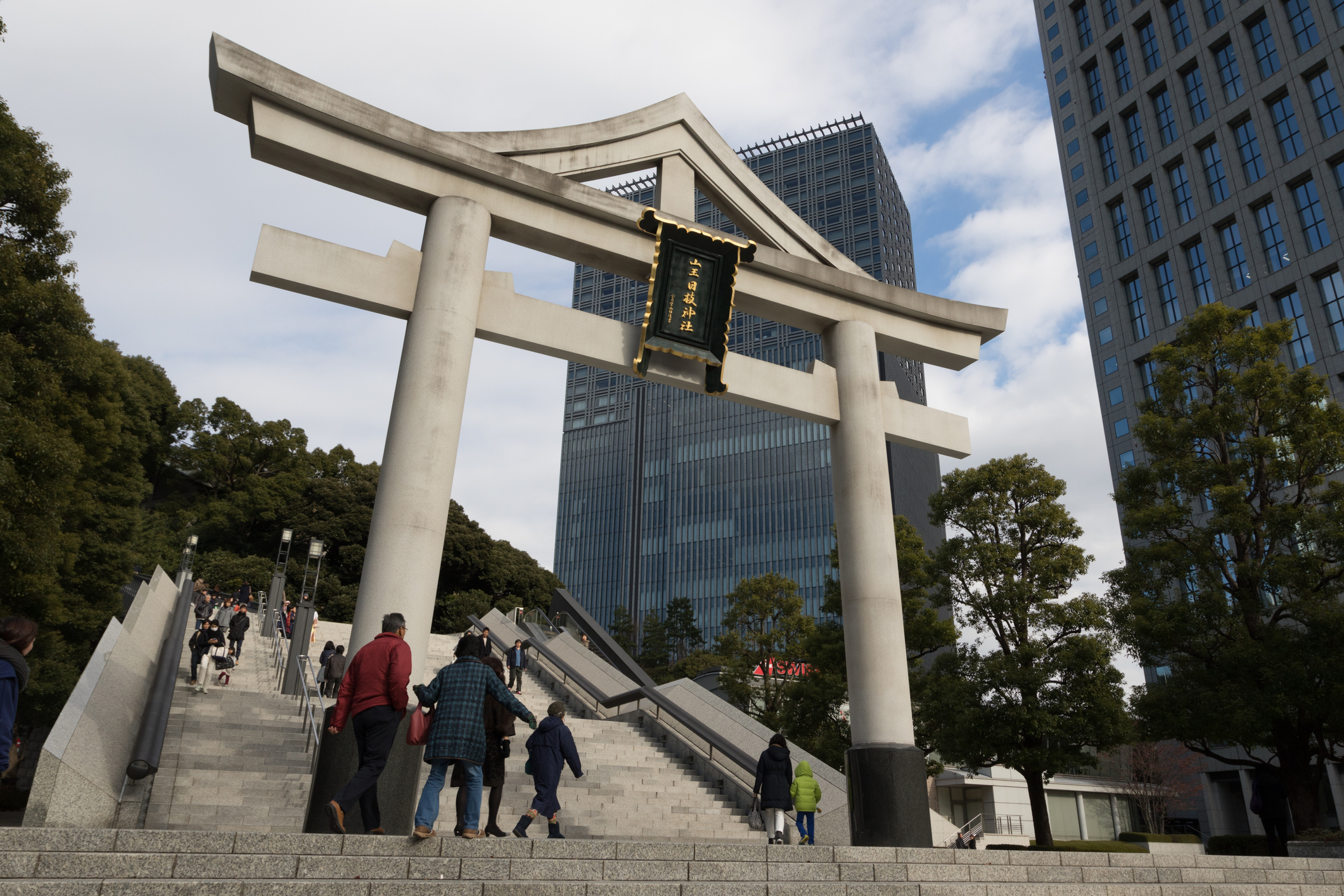

Among the many charming festivals celebrated by Old Japan, the most romantic was the festival of Tanabata-Sama, the Weaving-Lady of the Milky Way. In the chief cities her holiday is now little observed; and in Tokyo. it is almost forgotten. But in many country districts, and even in villages, near the capital, it is still celebrated in a small way. If you happen to visit an old-fashioned country town or village, on the seventh day of the seventh month (by the ancient calendar), you will probably notice many freshly-cut bamboos fixed upon the roofs of the houses, or planted in the ground beside them, every bamboo having attached to it a number of strips of colored paper. In some very poor villages you might find that these papers are white, or of one color only; but the general rule is that the papers should be of five or seven different colors. Blue, green, red, yellow, and white are the tints commonly displayed. All these papers are inscribed with short poems written in praise of Tanabata and her husband Hikoboshi. After the festival the bamboos are taken down and thrown into the nearest stream, together with the poems attached to them.

**************

The ceremonies at the Imperial Court were of the most elaborate character: a full account of them is given in the Kōji Kongen,—with explanatory illustrations. On the evening of the seventh day of the seventh month, mattings were laid down on the east side of that portion of the Imperial Palace called the Seiryōden; and upon these mattings were placed four tables of offerings to the Star-deities. Besides the customary food-offerings, there were placed upon these tables rice-wine, incense, vases of red lacquer containing flowers, a harp and flute, and a needle with five eyes, threaded with threads of five different colors. Black-lacquered oil-lamps were placed beside the tables, to illuminate the feast. In another part of the grounds a tub of water was so placed as to reflect the light of the Tanabata-stars; and the ladies of the Imperial Household attempted to thread a needle by the reflection. She who succeeded was to be fortunate during the following year. The court-nobility (Kugé) were obliged to make certain offerings to the Imperial House on the day of the festival. The character of these offerings, and the manner of their presentation, were fixed by decree. They were conveyed to the palace upon a tray, by a veiled lady of rank, in ceremonial dress. Above her, as she walked, a great red umbrella was borne by an attendant. On the tray were placed seven tanzaku (longilateral slips of fine tinted paper for the writing of poems); seven kudzu-leaves; seven inkstones; seven strings of sōmen (a kind of vermicelli); fourteen writing-brushes; and a bunch of yam-leaves gathered at night, and thickly sprinkled with dew. In the palace grounds the ceremony began at the Hour of the Tiger,—4 A.M. Then the inkstones were carefully washed,—prior to preparing the ink for the writing of poems in praise of the Star-deities,—and each one set upon a kudzu-leaf. One bunch of bedewed yam-leaves was then laid upon every inkstone; and with this dew, instead of water, the writing-ink was prepared. All the ceremonies appear to have been copied from those in vogue at the Chinese court in the time of the Emperor Ming-Hwang.

It was not until the time of the Tokugawa Shōgunate that the Tanabata festival became really a national holiday; and the popular custom of attaching tansaku of different colors to freshly-cut bamboos, in celebration of the occasion, dates only from the era of Bunser (1818). Previously the tanzaku had been made of a very costly quality of paper; and the old aristocratic ceremonies had been not less expensive than elaborate. But in the time of the Tokugawa Shōgunate a very cheap paper of various colors was manufactured; and the holiday ceremonies were suffered to assume an inexpensive form, in which even the poorest classes could indulge.

**********************

For an authoritative overview of the origins and development of Tanabata festivities, please see this site.

********************

Japan Today feature, 7/7

Tanabata wishes

Visitors attach paper strips with their wish written on them to a bamboo branch for the Tanabata Star Festival at a temple in Tokyo on Tuesday. According to legend, deities Orihime (Vega) and her lover Hikoboshi (Altair), separated by the Milky Way, are allowed to meet only once a year during this period. People celebrate the festival by writing wishes on strips of paper and hanging them under bamboo trees.