The cliff-hugging Yamadera in Yamagata Prefecture

What is it about rock temples? Some of the most stunning spiritual sites are those that perch on cliffsides in China and Burma. Tohoku too boasts the wonderful Yamadera. And on my recent World Heritage trip to the Deep North, I was delighted to come across two more little treasures set in rock.

One of the discoveries was the Takkoku no Iwaya, outside Hiraizumi in Iwate Prefecture. The other was Oya Temple, near Utsunomiya which is the gateway to Nikko. Both reflect the mountain yearnings of esoteric Buddhism; both are embedded in the spirit of rock; and both are deeply syncretic.

Shinto of course has a close connection with rock. Its gods arrive by rock-boats; kami manifest in large boulders; and Amaterasu withdrew into a cave when she fell out with her sibling Susanoo. Some of my favourite shrines are set near cliffsides and honour large rocks as the ‘body-spirit’ (goshintai) of their kami. You could say indeed that Japanese religions are no less built upon rock than Judaism and Christianity!

A Tendai temple

Rock-cliff temple near Hiraizumi, Iwate Prefecture

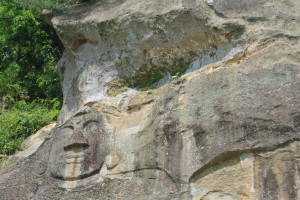

Cliff face at Takkoku

The Tendai temple of Takkoku no Iwaya (pictured above) was established after the military leader Sakanoue no Tamuramaro claimed the area in 801 on the orders of Emperor Kammu to subdue the ‘northern barbarians’. He gave thanks by having a hall dedicated to Bishamonten (deity of conflicts). It was modeled on Kiyomizu-dera Temple in Kyoto, and being a long-term citizen of the ancient capital I’m always pleased to find echoes of the city in far-flung parts of the country.

A Buddhist image (see left) was carved on the rock beside the hall, as if the cliff itself has grown a face. Temple and mountain, human and nature, seem here perfectly complementary. In the main hall stands the imposing figure of Bishamonten. As one of the Seven Lucky Gods, the deity is a well-known figure in Shinto shrines where he and his colleagues often show up in a Lucky Treasure Boat. Buddha or kami? For Tamuramaro, perhaps it spanned the divide.

A Shingon Temple

Oya Temple, outside Utsunomiya

Oya Temple also claims a ninth-century foundation, in this case by the legendary Kukai (also known as Kobo Daishi). That shows it belongs to the Shingon sect, said to be the closest in Japan to tantric Buddhism. Its cosmos is filled with numerous Buddhas, some of which are carved out of the cliff-face in which the temple is set. Recent work has shown the site to have Jomon remains, dating back as far as 10,000 years.

Inari shrine guards over Oya Temple

The cliff setting has resulted in a closeness to nature and awareness of its numinous power, made manifest in a protective shrine to Inari which guards over the temple. Shinto is said to be a religion of awe, and there is definitely something awe-inspiring about the surrounding setting and sculpted artwork at Oya.

The awesomeness is nowhere more apparent than in the massive Heiwa Kannon which was carved by hand out of the nearby rocks from 1948-54. It remains the largest stone Buddha in Japan. Dedicated to the war dead, it also serves to draw visitors to the area, as the nearby coach park attests.

Religious devotion or tourist attraction? The two have long gone hand-in-hand in Japan, since the erection of the Great Buddha of Nara in 751 if not before. Hachiman was brought from Usa in Kyushu to act as protective guardian at Nara. Here at Oya, Inari fulfills a similar function.

One type of deity (buddha) is represented in rock; the other (kami) is invisible but manifest in rock. Despite the best endeavours of the Meiji ideologues to separate Shinto and Buddhism for nationalist ends, the interconnectedness of the two faiths is set in the rock of ages. Complementary and symbiotic, the natural syncretism of Japan continues to find its greatest expression in the rhythms of rock.

The Heiwa Kannon, largest stone buddha in Japan at 27 meters tall

Mongolian grand sumo champion Yokozuna Hakuho performs the “ring entering ceremony” during a dedication at Meiji Shrine, Tokyo, Japan, on January 6, 2012. {Photo UPI/Keizo Mori}

Mongolian grand sumo champion Yokozuna Hakuho performs the “ring entering ceremony” during a dedication at Meiji Shrine, Tokyo, Japan, on January 6, 2012. {Photo UPI/Keizo Mori}