Polychromed detail at Toshogu Shrine

A syncretic mausoleum

As the centrepiece of Nikko, Toshogu is one of the most famed destinations in Japan. Ornate, colourful, elaborate, it acts as mausoleum for Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616), founder of Japan’s most successful shogunate dynasty,.

Unfortunately for me, my visit happened to coincide with a holiday weekend, so that the shrine was overrun with daytrippers. On the other hand, I was fortunate to have with me the entry from Joseph Cali’s forthcoming book on Shinto Shrines. It not only provides a guide to the physical features, but explains the historical and spiritual background.

“The area is rightly famous for its natural beauty, and long before Ieyasu was enshrined at Toshogu, Nikko was an important center of shugendo mountain asceticism. The origin of the shrine-and-temple complex is the area around Mount Nantai. Together with Mounts Nyoho and Taro, it became one of the three holy mountains of Nikko.”

The original shrine and temple, founded in the eighth century, have evolved into the present-day Futarasan Jinja and Rinno-ji, which stand just next to Toshogu in the woods. Together the three institutions make up the World Heritage Site of Nikko. It’s a must-see for anyone visiting Japan.

Ieyasu's grave, visited by climbing a few hundred steps

Deification of a shogun

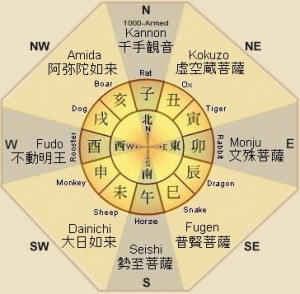

Ieyasu’s wish to be enshrined here came at an interesting time in Japan’s religious development, as Cali makes clear. Yoshida Shinto was making an attempt at primacy by denigrating Buddhism as a foreign religion. But Tendai Buddhism based on Mt Hiei came up with a strong counter-theory….

A wish-fulfilling tree at Ieyasu's grave

‘Around the time of Ieyasu’s death,’ writes Cali, ‘the monk Tenkai (1536-1643) devised the doctrine of Ichiijitsu Shinto…. According to this doctrine, Ieyasu is a manifestation of the Buddha in the form of Tosho Daigongen.’ [Gongen is an avatar, in this case a Shinto avatar of a deeper Buddhist reality.]

The first Japanese leader to be posthumously apotheosised was Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536-98), at his own command. But with the defeat of his Toyotomi clan at the battle of Sekigahara in 1600, his cult soon fell into desuetude. It was supplanted by the Great Avatar, Illumination of the East, as Ieyasu was posthumously titled ~ Toshu Daigongen.

Work started in earnest in 1634, with a small army of 15,000 people. Two years later, in time for the twentieth anniversary of Ieyasu’s death, the project was completed. Toshogu alone has 42 buildings, while Futarasan Jinja has 23 and Rinno-ji 16 (with a further 22 at the mausoleum of Ieyasu’s grandson, Iemitsu). ‘It represents the greatest expression of power and wealth of any group of structures in Japan,’ comments Cali.

Real elephants or imaginary animals?

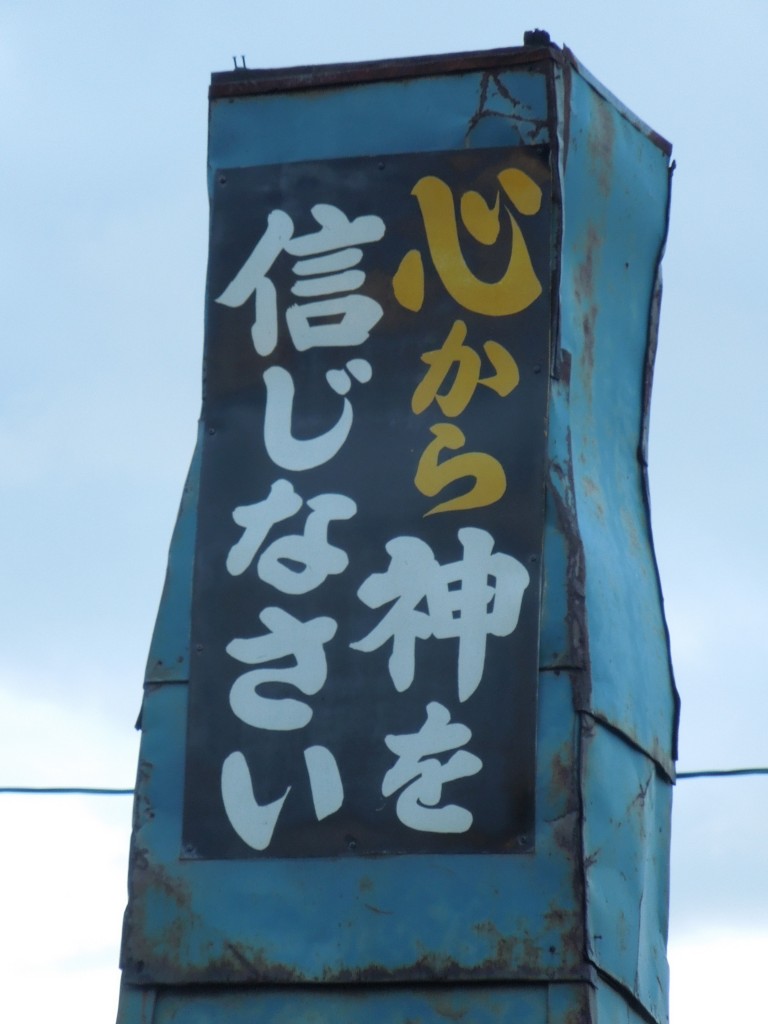

Meiji separation

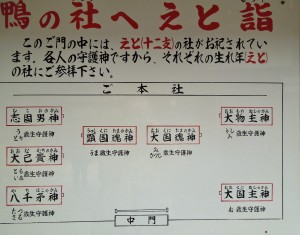

In its desire to differentiate itself from Tokugawa Buddhism, the Meiji government of 1868 decided to artificially make Shinto into a distinct religion. At the syncretic complex of Nikko, they faced a hard task. The temple of Rinno-ji was physically relocated to enforce its separateness, but nonetheless some striking examples of syncretism remain, as Cali’s guide makes clear.

Inside the Shinto torii marking the approach to Toshogu stands a five-storey Buddhist pagoda. Both represent examples of Edo engineering skills. The torii has joints in its crossbeams to allow for movement in case of earthquakes, while the pagoda has a central pillar to provide stability (a feature deployed in the recently constructed Tokyo Skytree, tallest tower in the world and second only in height to Dubai’s Burj Khalifa).

At the entrance to Toshogu is another striking example of syncretism. In place of the usual guardians is a Niomon gate housing the two terrifying figures that guard Buddhist temples. Cali tells us that these were removed to Rinno-ji by the Meiji government, but intriguingly made their way back here in 1897.

Inside is a veritable treasure house of imagery and polychromed patterns. One single gate – the Yomeimon – has more than 500 statues. Taken overall, the shrine has an interesting menagerie of real and imaginary creatures. There’s an elephant done by someone who had clearly never seen a real one. There’s the life cycle of a monkey, which includes the trio of ‘see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil’. And there’s a cat sleeping near some sparrows, which famously symbolises the peace and harmony Ieyasu brought to the realm.

The Tokugawa legacy is exemplified in the sumptuous display of arts that even today continues to draw gasps of astonishment from those who come to visit. Shinto could be said to centre around the ancestral cult of the imperial family, founded by Amaterasu the sun-goddess. Here however is an alternative vision, raised to the founding figure of a shogunate dynasty. Nothing could be further removed from the simplicity of the wooden structures at Ise!

As the saying goes, ‘Never say kekko (wonderful) until you’ve been to Nikko.’

One of the grandest hand-washing basins you're ever likely to see!

Tokugawa splendour: you can't get more sumptuous than that!

*******************************************************************************************

For Cali and Dougill’s guide to Shinto Shrines, see http://www.uhpress.hawaii.edu/p-8926-9780824837136.aspx