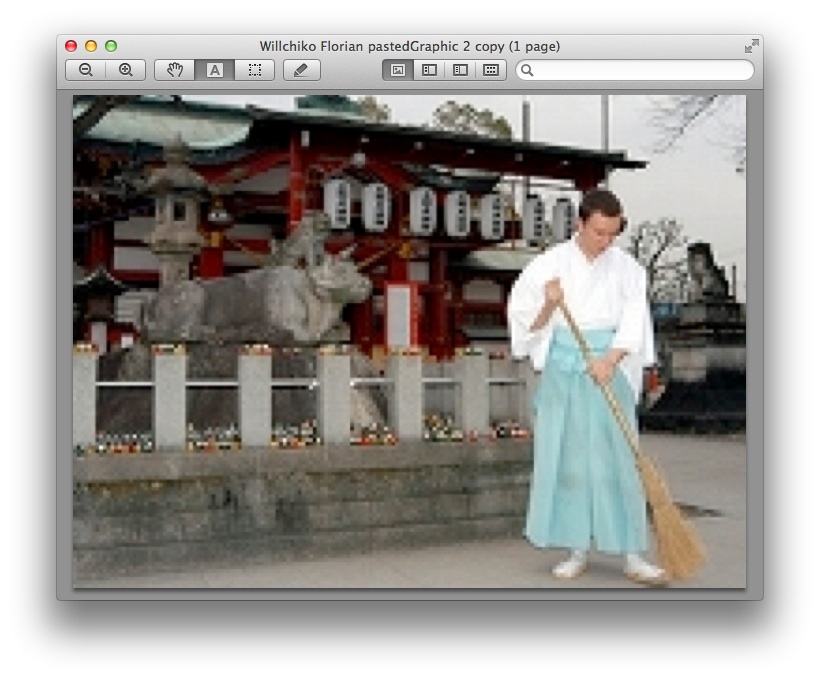

Shimogamo Jinja's sacred grove

The Greening of Shinto

Last weekend I went to a talk on Sacred Landscapes in Britain by Martin Palmer who runs an organisation called ARC (Alliance of Religions in Conservation). There were many fascinating aspects, but the most striking in Shinto terms was that ancient Long Barrows in Britain served as ritual sites for ancestor worship. More of that, later.

Martin Palmer’s organisation works with sacred forests worldwide, and he himself has worked a lot in China where Daoism and Buddhism are beginning to claw back some of the influence lost under Communism. I took the opportunity to ask him about Japan and Shinto, in response to which he told me of conversations he’d had with representatives of Jinja Honcho (Association of Shrines).

When they first asked to join the organisation around 2000, he asked them whether they were concerned only with kami in Japan or with kami everywhere. When they responded that there were only kami in Japan, he told them that it was impossible for them to join because the organisation was predicated on a global and universal basis. There could be no narrow nationalistic concern for sacred landscapes in one country only.

When they first asked to join the organisation around 2000, he asked them whether they were concerned only with kami in Japan or with kami everywhere. When they responded that there were only kami in Japan, he told them that it was impossible for them to join because the organisation was predicated on a global and universal basis. There could be no narrow nationalistic concern for sacred landscapes in one country only.

The rejection apparently came as a shock to Jinja Honcho and led to eighteen months of internal discussions, following which the representatives came back and said that kami must exist overseas as well and that therefore they were concerned with sacred landscapes worldwide. Membership of ARC duly followed.

Since that time Jinja Honcho has thrown themselves into the activities of ARC and are involved with projects that concern the management of forests in overseas countries. For progressives, this is a great leap forward in the internationalisation of Shinto and a welcome sign of the slow but steady opening up of the religion to the wider world.

One day the tribal may truly become global.

The path to globalisation?