View towards the main shrine

Fox, messenger of the kami Inari

May. Sunshine. Fertility. Inari…..

What a blessing at this time of year to live in Kyoto and be able to walk up the sacred mount at Fushimi. I’ve never seen the shrine so radiant, for it stands freshly restored and repainted. The vermillion colours sparkled in the sunshine, and the lacquered woodwork stood pristine against the verdant surrounds. The spirit of place was clearly delighted, happy to receive the pilgrim tourists drawn to its slopes.

Inari was founded in 711 by a member of the influential immigrant Hata clan. There’s a hokora (small shrine) dedicated to him as you mount the steps behind the main shrine. Further up the hillside there’s an iwakura (sacred rock) for him too. I often pay respects there, and while doing so I recall the curious founding myth of the shrine.

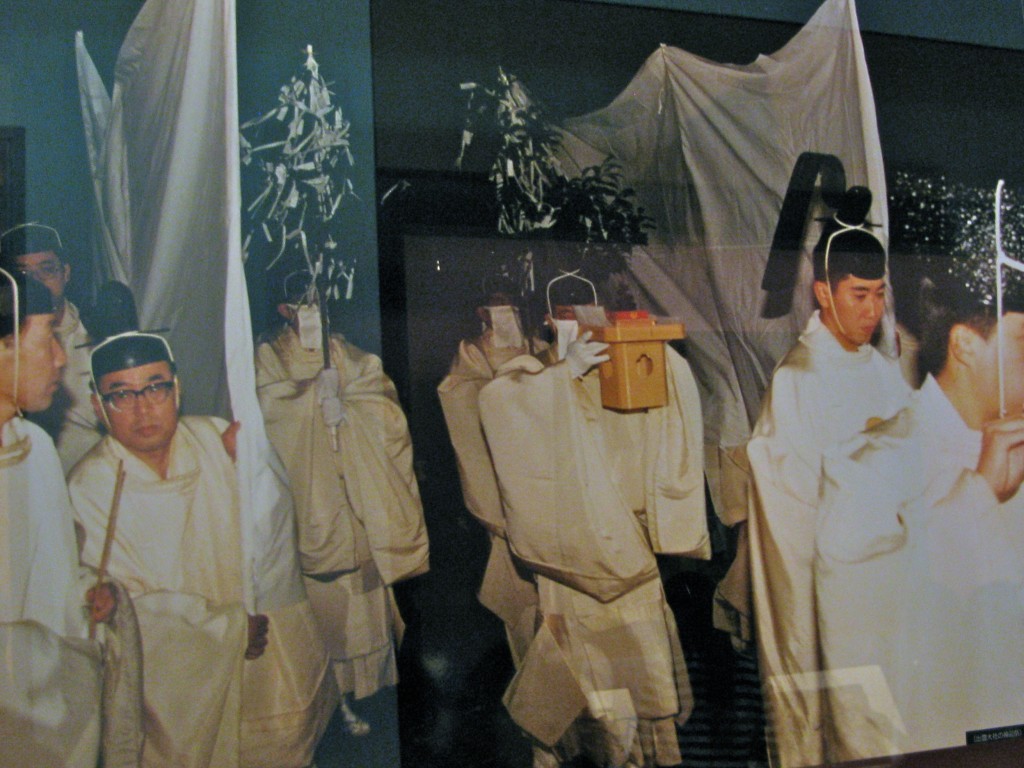

Foundation myth

Legend has it that clan leader Hata no Irogu one day used a large white rice cake (mochi) as a target for archery practice. When his arrow pierced the cake, a white bird flew up to the top of the hill and settled in a tree beneath which a rice field appeared. Seeing this, Irogu was moved to found a shrine.

One interpretation is that since rice was the staple of life for ancient Japanese, it was regarded as sacred, so shooting at a rice cake was sacrilegious. Consequently the rice spirit took flight and by revealing the newly grown rice field indicated the miraculous nature of the crop. Realisation of its vital role in the life of man led Irogu to build a shrine in gratitude to the ‘earth goddess’ that caused the grain to grow.

For myself, however, I can’t help seeing Taoist symbolism in the myth. A white circle; a red arrow; penetration. In the coming together of yin and yang was born new growth, crops, the stuff of life. The fertility theme is reinforced by subsequent developments, for the shrine’s original kami, known as Ugadama or Ugamitama no mikoto, became Inari in Heian times when it merged with the fertility couple of Sarutahiko (a deity with a phallic nose) and Ame no Uzume (a dancer who exposed her genitalia). Later still two others were added, so that Inari became a ‘five pillar’ deity, worshipped today as the deity of rice.

Inside a tunnel of torii, celebrating the rebirth

Tunnels and foxes

Fushimi is the head of some 30,000 Inari shrines around the country, characterised by their red tunnels of torii. Fushimi itself boasts some ten thousand altogether, and passing through the lower tunnels is a symbolic marker as one ‘enters into the mountain’.

For many, Fushimi is more than a form of tourism; it’s a form of pilgrimage. In ascending to the topmost altar, one sloughs off the mundane and takes on a new persona in the rarified air of the hill. Physical exertion is accompanied by spiritual refreshment, so that returning through the womb-tunnel one is symbolically reborn. (As Inari is a fertility goddess, she is also associated with childbirth.)

Key holder

Just as numerous and noticeable as the torii are the statues of foxes, messengers of the kami. Sometimes the animal holds in its mouth an ear of rice, or the key to the rice granary. Sometimes too it carries a wish-fulfiling jewel. Here again there may be a fertility element, for the key is a phallic symbol and the jewel a female symbol.

Continental foxlore which entered from China in the eighth and ninth centuries attached itself to the Fushimi deity, and the Hata clan made a cult of the animal. Foxes are liminal creatures, that hover on the edge of woodland and move mysteriously in the twilight. In this way they came to capture the Japanese imagination.

Rise to prominence

Already from the early ninth century the shrine developed strong Buddhist connections, for the founder of the Shingon sect, Kukai (774-835), used wood from Mt Inari to build his Kyoto headquarters at Toji and enshrined the kami as the temple’s protecting deity. (The Buddhist version of Inari has a boddhisattva named Daikiniten riding witchlike on a flying white fox.)

A noticeboard at Fushimi says that the shrine first came to national attention in 852 after successful prayers for rain, and later it was included among the prestigious 22 Shrines deserving imperial patronage. By Edo times it was established as a magical Shinto-Buddhist complex with strong drawing power. ‘If sick pray to Kobo Daishi (i.e. Kukai), if making a wish pray to Inari,’ ran a popular saying.

The kami was among the most accessible for ordinary folk, especially women (many Buddhist places, including sacred mountains, were off-limits to women). Perhaps as a result, Inari became a focus for female shamanic types working with healing. divination and other-worldly contact. Tales of fox-possession were rife, and ridding a person of the fox-spirit a common means of treatment for physical and mental ailments.

Guardman at the entrance to the shrine

It was in this age too that the shrine became associated with wealth and business. Rice was used for currency and taxation, with peasants forced to hand over the greater part of their yield to the daimyo (lords). (In Edo times the total rice levy was 30 million bushels, of which the Tokugawa took 7. Next to them were the Maeda lords of Kanazawa, notable for their hyakumanben income (1 million bushels).

As a result Inari is today one of Japan’s most flourishing shrines, with the highest number of New Year visitors in Kansai. The constant stream of purifications attests to its appeal. It’s particularly popular with businesses, which patronise it in the hope of winning success.

Highs and lows

In her book The Fox and the Jewel Karen Smyers describes the tensions that exist between believers who frequent the upper reaches of the hill and the shrine nestled at its base. She casts it in terms of a clash between a female shamanic tradition and the male priests. The former seek direct contact with the kami on the private land above the shrine; the latter follow ceremonial order and propriety. One strand of Inari worship inclines to mysticism and individualism, the other to rationalism and conformity. (It’s a division that reminds me of neighboring Korea, where I once attended a female shamanic rite which preceded a male-dominated Confucian ceremony – both celebrating the same event yet very, very different in nature.)

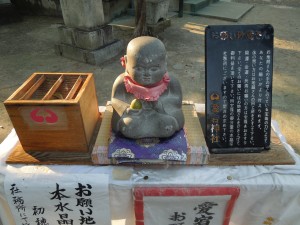

One of the 10.000 'otsuka' altars on Inari hill

There are some 50 priests working at Fushimi, all of whom are male. There are also some 600 ‘ko’ (fraternities) associated with the shrine, which centre their belief around Mt Inari and make pilgrimages to the hill. Many of them are far from orthodox, some being led by shamanic figures and some by Buddhists.

I’ve often come across groups performing rituals in front of a particular ‘otsuka’, or altar. There are some ten thousand of these rock monuments, which were put up for the most part in a spontaneous development at the end of the Edo era. They were initially opposed by the shrine’s priests, who saw control slipping out of their hands. Now, sensibly, they sanction and regulate the erection of the otsuka, charging some Y16,000 for the privilege.

Each of the otsuka bears a name or names of the manifestation in which Inari appeared to the worshipper ~ Great Being of Light, for instance. It’s said that the names are revealed in the dreams of believers, prompting them to put up a monument to their personalised manifestation, complete with fox guardians. In many cases family descendants continue to visit the monument, and one often sees fresh offerings and newly sewn red bibs on the foxes.

On a visit once I was puzzled to hear what sounded like Buddhist prayers being chanted though I could see no people. As I made my way towards where the voices were coming from, I virtually fell on top of a small group crouched in a hollow before a particular rock, on which lay offerings of rice and saké. Here on the hilltop I had a sense of how worship must have been in ancient times – outdoors, direct and informal. Here, you could say, the spirit of place was in situ.

Inari in her female form as goddess of rice (the deity also has a male manifestation in the form of an old man)

It’s the one-year anniversary of this blog, and I couldn’t have asked for a better year… There have been over 170.000 hits, far more than expected, and the positive feedback has given me the incentive to keep posting and to try and improve the content…

It’s the one-year anniversary of this blog, and I couldn’t have asked for a better year… There have been over 170.000 hits, far more than expected, and the positive feedback has given me the incentive to keep posting and to try and improve the content…