If one can presume that ancient Japanese had close links with Korean shamanism, and that Korean shamanism derived from that of Mongolian/Siberia through southern migration, then it would be surprising if there were not close affinities between Shinto and Mongolian shamanism. Below are just a few of the similarities. The list could be easily extended, but I think it suffices to show how closely Shinto is bound to East Asian shamanism.

The cave at Takachiho into which Amaterasu supposedly withdrew

Worldview

Mongolian shamanism, indeed shamanism in general, is animistic, polytheistic, and aims at living in a state of harmony or balance with the world. There are countless deities and spirits, including ancestral, spirits of place, and beings that live in the upper world (tenger in mongolian is cognate with tenjin in Japanese). There’s no fixed doctrine and no holy books. Ancestor worship blends into nature spirits. In Mongolia ancient legend tells of the sun goddess Naran Goohon becoming sick and making the world dim but being restored after a meeting of the gods. In Shinto Amaterasu retreats into a cave, making the world dim, but light is restored after a meeting of the gods.

3 worlds

In Mongolian shamanism there is an upper world, this world and a lower world where the dead go. The

lower world is dimmer than ours and can be entered through caves and tunnels etc. Human souls awaiting reincarnation can be found there, and it operates with only half a sun and half a moon. The upper world is brighter than ours and is where the chief deities reside. In Shinto mythology there is an upper world called Takamagahara (High Plain of Heaven) where the chief deities reside, as well as earth and an underworld (Yomi) where the dead reside.

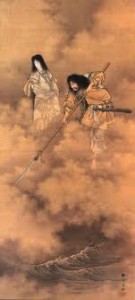

Izanagi and Izanami on the floating bridge of heaven

Bridge to heaven

In Mongolian mythology a rainbow connects the upper world and this world. In Shinto mythology the two worlds are joined by Ama no ukihashi, the floating bridge of heaven, commonly thought of as clouds or a rainbow.

Dreams

In both Shinto and Mongolian shamanism dreams are messages sent by the spirits. They often disclose sacred sites or events of special significance. The location for many Shinto shrines and the identity of kami were ‘revealed’ in this way.

Mongolian ritual 'minaa' used to whip away impurities (courtesy of 3worlds website)

Pollution and Purification

Both Mongolian shamanism and Shinto believe that spirits are offended by disrespect, lack of hygiene, the violation of taboos, or contact with blood and death. Merit accumulates through an upright life, religious acts and sacrifices. Before rituals, purification is carried out with such means as smoke, salt, fasting and washing. A ‘spiritual cleaner’ is used to sweep away impurities (minaa in Mongolian, haraigushi in Japanese). The minaa can be used like a whip to clear negative energy, and is also applied to the body as a means of healing.

Sacred tree with shimenawa at Omiwa Jinja

Sacred trees

Trees are seen as a manifestation of the earth’s power, and remarkable trees represent a special mark of the lifeforce. Ribbons or silk scarves are tied to their branches in Mongolia; in Japan sacred trees are marked with a shimenawa rice rope.

Ancestral spirits

In both Mongolian and Shinto traditions, human spirits are thought to remain behind after death as protector and helper of the household. After several generations they no longer remain as individual entities but merge into an anonymous whole. Those who exhibit exceptional power, such as Chingis Khan and Tokugawa Ieyasu, are worshipped as deities regardless of anything to do with morality

Angry spirits

In both Mongolian and Shinto traditions, people who die too young or unjustly may plague descendants and need placating. Also those who are too strongly attached to things in this world may linger on unrequited.

Animal familiars

In Mongolia animal spirits are used by shamans as aides in their otherworldly journeys. Totem animals play a symbolic role as ancestors of various clans, and deities may be associated with a particular animal. In Shinto animal spirits once also served as figureheads for clans and deities. Deer for the Fujiwara clan; crow for the Kamo clan; fox for Inari; dove for Hachiman, etc.

Spirit bodies

In both Mongolian shamanism and Shinto, objects made of material such as wood and rock, or simply a doll or a paper drawing, are used as a ‘spirit body’. The spirit is drawn into the object in a special rite conducted by the shaman/priest.

Shinto drum on display during a ritual at Yoshida Jinja

Drums, bells and rattles

In shamanism the rhythmic repetition of the drum, quickening in tempo, leads to an altered state of consciousness. In Shinto the drum is a treasured item. In Mongolia bells and rattles are thought to attract the attention of the spirits. In Shinto a bell is rung at the shrine to attract the kami, and miko use a kind of rattle (suzu) when dancing in order to catch the kami’s attention.

Divination

In Mongolian shamanism, as well as ancient Japan, the shoulder blade of a sheep or deer was burnt in order to interpret the burns and cracks. Divination remains an important part of Shinto and shamanism.

Communion

At the end of rituals in both Mongolia and Shinto, participants partake in food or beverage as a means of communing with fellow humans and with the spirits.

Mirrors

Mirrors play a very special part in shamanism. Ancient mirrors are thought to possess a spirit, and they act as important sources and absorbers of energy. Shamans wear round mirror discs on their robes. In Shinto the mirror was elevated into a central focus of worship, as representative of the spirit of Amaterasu.

Shaman costume (courtesy of the Danish National Museum)

Manchurian shaman's costume

The pictures here come from a site called Mongolian Shaman, which has this to say on the subject of the shaman’s mirror. “The heavy shaman’s mirrors act in a double capacity – they protect the shaman by deflecting harm, while revealing what is normally invisible to the human eye. The number of mirrors on the costume indicates the shaman’s powers and maps a geographical cosmos. By wearing the costume, the shaman is located in the centre of this cosmos. During performance, a shaman is seized by one or more ancestral spirits, so that what is inside the mirror-costume is the spirits, rather than the shaman’s body. Here, the body is something open to forces that can control it, inhabit its form and shape its physical features.”

**********************************************************************************************************************************************

Information draws on two books by Mongolian shaman Sarangerel – Riding Windhorses (2000) and Chosen by the Spirits (2001). The author was born in the US of Mongolian stock, and went to Siberia for training then worked closely with the shaman centre in Ulan Bator. Sadly she died in 2006, aged just 43.