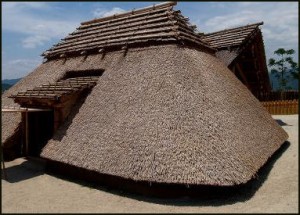

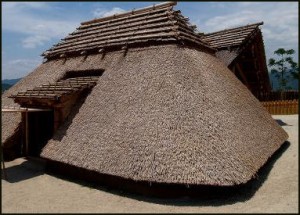

Yayoi housing (courtesy of Ray Kinnane)

Around 500-300 BC a wave of continental incomers arrived into Japan who were genetically and culturally different from the Jomon natives. They may have entered from Korea, or from China via Korea, or even directly from China. Most likely a combination of all three. These Yayoi newcomers brought with them a brand new culture based on wet rice cultivation, together with weaving, metalworking and a more advanced form of pottery. “DNA tests have confirmed the likelihood of this hypothesis. About 54% of paternal lineages and 66% of the maternal lineages have been identified as being of Sino-Korean origin,” says this site.

These newcomers brought with them two different strands of East Asian religion. A southern, Chinese agricultural-based strand. And a northern, Siberian shamanistic strand. What could bring these two together? Migration routes into Korea, it seems.

Wet rice culture started in the area around around the current border between Myanmar and China. In around 400 BC, it spread widely over the lower Yangtze region, before the Han (Chinese) people settled there. It seems the people from there didn’t go directly to Japan, but moved first into the southern part of the Korean peninsula. The reason is unknown, but probably fighting drove them to look for a more peaceful place. The fact that rice culture didn’t enter directly into Japan meant that it arrived with many features of Northern Tungusic culture, which had migrated southwards into the Korean peninsula. This mixing of northern and southern strands led to the fusion in Shinto of Siberian shamanism with Chinese folk elements based around the agricultural cycle.

Yayoi-era symbols of spiritual authority: mirror, sword and magatama jewel

Now let’s see what Wikipedia has to say on the subject….

“The origin of Yayoi culture has long been debated. Chinese influence was obvious in the bronze and copper weapons, dōkyō, dōtaku, as well as irrigated paddy rice cultivation. Three major symbols of the Yayoi culture are the bronze mirror, the bronze sword, and the royal seal stone.

“In recent years, more archaeological and genetic evidence has been found in both eastern China and western Japan to lend credibility to this argument. Between 1996 and 1999, a team led by Satoshi Yamaguchi, a researcher at Japan’s National Science Museum, compared Yayoi remains found in Japan’s Yamaguchi and Fukuoka prefectures with those from China’s coastal Jiangsu province, and found many similarities between the Yayoi and the Jiangsu remains.

“Some scholars also concluded that Korean influence existed. These include “bounded paddy fields, new types of polished stone tools, wooden farming implements, iron tools, weaving technology, ceramic storage jars, exterior bonding of clay coils in pottery fabrication, ditched settlements, domesticated pigs, and jawbone rituals. This assumption also gains strength due to the fact that Yayoi culture began on the north coast of Kyūshū, where Japan is closest to Korea. Yayoi pottery, burial mounds, and food preservation were discovered to be very similar to the pottery of southern Korea.”

I would add to the above the influence of Korean shamanism, particularly in the form of miko possession and rock worship. ‘Fossilised shamanism’ is how Gunther Nitschke describes Shinto in his book From Ando to Shinto (1993), but there’s more to it than that… it’s a concoction, with a fair dose of Daoism and Confucianism added later for good measure.

Yayoi-era doutaku bell

It’s thanks to these diverse roots that Shinto is so rich a religion. To what extent it can be called ‘indigenous’, however, is debatable. To me, it’s much more meaningful to call it East Asian. This is of course anathema to Japanese nationalists, who like to think racially and culturally Japanese are unique.

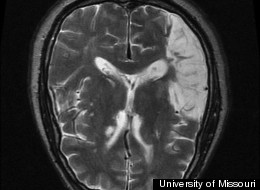

Based on skeletal, DNA and linguistic studies the scholar Satoshi Horai argues that modern Japanese are a mix of 65 percent Yayoi and 35 percent Jomon. Modern Japanese in the northern prefectures have rounder eyes, more body hair and wider faces, which suggests closer links to Jomon people. The archeologist Yasuhiro Okada told the New York Times, “People from northern Japan can be 60 to 80 percent of Jomon origin, while those from western or southern Japan are 40 percent Jomon or less.”

Based on skeletal, DNA and linguistic studies the scholar Satoshi Horai argues that modern Japanese are a mix of 65 percent Yayoi and 35 percent Jomon. Modern Japanese in the northern prefectures have rounder eyes, more body hair and wider faces, which suggests closer links to Jomon people. The archeologist Yasuhiro Okada told the New York Times, “People from northern Japan can be 60 to 80 percent of Jomon origin, while those from western or southern Japan are 40 percent Jomon or less.”

DNA analysis also indicates that Yayoi people and modern Japanese are similar genetically to modern Chinese and Koreans. This evidence strongly suggests that modern Japanese evolved from people who came from Korea or China, a notion that debunks the pre- World War II ideology that states that Japanese are racially distinct from other Asians. Some Japanese still hold this belief. In some museums in Japan you can find displays of ancient hunter-gatherers evolving into modern salarymen without any input from the Asian mainland.

DNA analysis also indicates that Yayoi people and modern Japanese are similar genetically to modern Chinese and Koreans. This evidence strongly suggests that modern Japanese evolved from people who came from Korea or China, a notion that debunks the pre- World War II ideology that states that Japanese are racially distinct from other Asians. Some Japanese still hold this belief. In some museums in Japan you can find displays of ancient hunter-gatherers evolving into modern salarymen without any input from the Asian mainland.

(The above is taken from an excellent website full of interesting facts and snippets about early Japanese: See http://factsanddetails.com/japan.php?itemid=484&catid=16&subcatid=105)

*********************************************************************************************

For the first part of this article, about Jomon Japanese and the Polynesian connection, please click here.

For information on Korean mountain worship and shamanism, see David Mason’s San-shin site here.

Korean priest - not unlike a Shinto priest

Korean offerings - not unlike Shinto offerings (except the pig's head!!)

Korean drum – with triple tomoe

Korean rock worship – origin of Japanese sacred rocks

Korean wrestling - much like sumo

Korean communal repaste after a ceremony – much like Japanese naorai

Based on skeletal, DNA and linguistic studies the scholar Satoshi Horai argues that modern Japanese are a mix of 65 percent Yayoi and 35 percent Jomon. Modern Japanese in the northern prefectures have rounder eyes, more body hair and wider faces, which suggests closer links to Jomon people. The archeologist Yasuhiro Okada told the New York Times, “People from northern Japan can be 60 to 80 percent of Jomon origin, while those from western or southern Japan are 40 percent Jomon or less.”

Based on skeletal, DNA and linguistic studies the scholar Satoshi Horai argues that modern Japanese are a mix of 65 percent Yayoi and 35 percent Jomon. Modern Japanese in the northern prefectures have rounder eyes, more body hair and wider faces, which suggests closer links to Jomon people. The archeologist Yasuhiro Okada told the New York Times, “People from northern Japan can be 60 to 80 percent of Jomon origin, while those from western or southern Japan are 40 percent Jomon or less.”