Otafuku mask at Kinefuri Matsuri (photo by mboogiedown)

Otafuku is a curious crossbreed character, familiar to anyone who lives in Japan. She’s a dumpy, homely, cheery faced figure who’s also a bringer of happiness. At some shrines she’s given out as an engimono (good luck charm). But who on earth is she?

Accordng to Hirata Atsutane (1776-1843), the erratic polymath of Shinto studies, there are two theories about her origins. (The following passage comes thanks to Norman Waddell’s translation in The Religious Art of Zen Master Hakuin.)

According to one source Otafuku first appeared around the end of the Ashikgaga period (1392-1569) as the name of a miko named Kamejo (Tortoise Woman) at a certain Shinto Shrine, whose face resembled the traditional mask known as Okame (Tortoise). She was devoted to the goddess Uzume no mikoto, and had a charming exuberance that seemed to radiate from her very being. Despite her homely appearance, her sincerity and purity of spirit was such that even a villain of the most dastardly stripe would undergo a change of heart just by gazing at her face. Because of this a mask resembling her was fashioned and given the name Otafuku (Much Good Fortune). From the beginning the name Otafuku became known through the land. However, there is another theory that Otafuku’s face was modelled after the goddess Uzume no mikoto.

Statue of Ame no Uzume at Takachiho Shrine

Uzume no mikoto is a well-known figure from Japanese myth. It was she who danced provocatively before the assembled kami when Amaterasu retired into the Cave, inducing guffaws and roars by lifting up her skirt and exposing herself. Later she was sent to entice Sarutahiko, when the Yamato clan “descended from heaven”.

Otafuku too has a sexual connotation and is known as a fertility symbol. But whereas accounts of Ame no Uzume usually suggest she was beautiful, Otafuku is regarded as plain albeit homely and humorous. So how is one to explain the association with the divine Uzume?

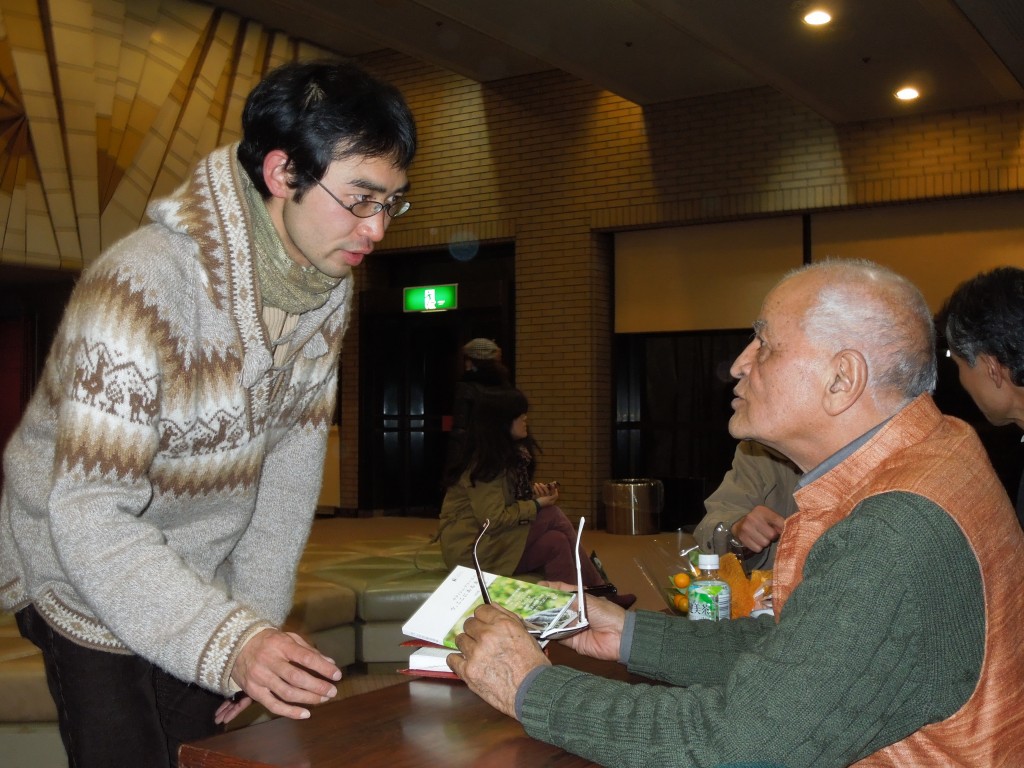

Katsuhiro Yoshizawa, author of the book on Hakuin, has an intriguing suggestion. Perhaps, Uzume resembled the ideal of feminine beauty in classical Japan – a stout-looking woman with full cheeks and thick black eyebrows.

The depictions of Ame no Uzume I’ve come across certainly look like that. In which case it occurs to me then that Otafuku might represent a later caricature of the ancient ideal… an extension for comical effect that plays on the sexual attractiveness and turns her into a figure of fecundity (her cheeks are said to resemble buttocks).

Known also as Ofuku and Okame, Otafuku is a popular figure in folk tales and paired with a male caricature called Hyottoko, also with podgy cheeks. With her ribald and good-hearted nature she spreads a smile whenever she appears. She features too in Shinto festivals, and here’s an example from the Kokugakuin online encyclopedia:

An annual festival held September 16 at Togakushi Shrine in Wara Village, Gujō District, Gifu Prefecture. On the day of the festival, two large floats are decorated with mechanical dolls. The dolls on one float represent priests while the other float carries dolls that bear the faces of a plump, cheery woman (otafuku), a good luck symbol.

Priests and cheery women. Now I wonder how that connection arose…..

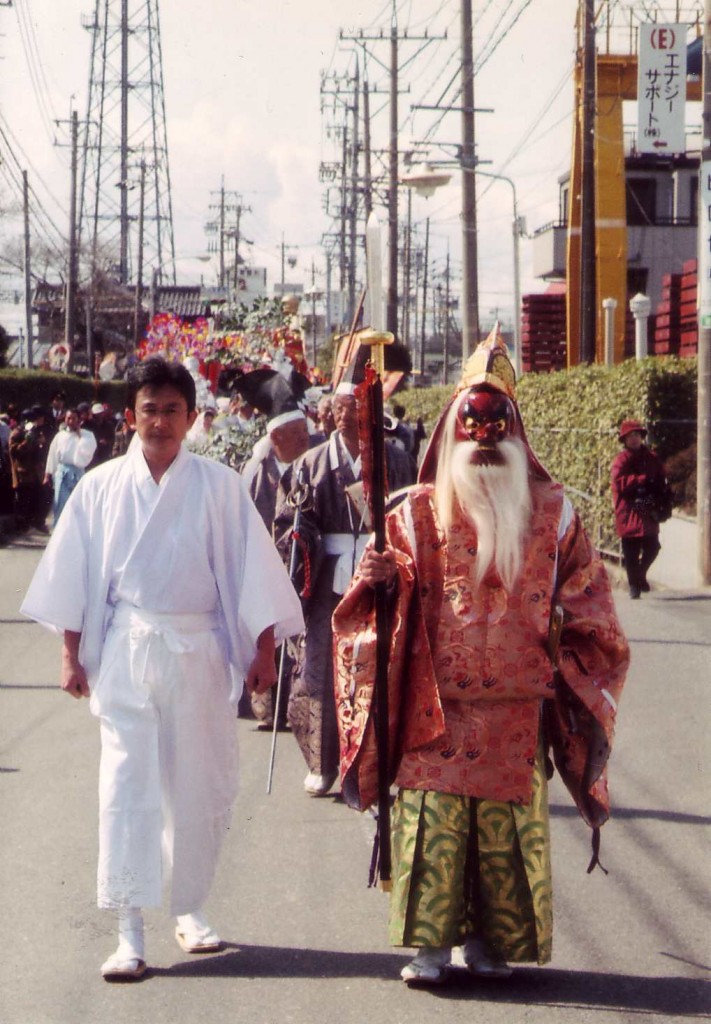

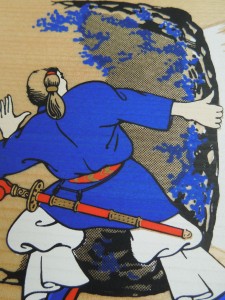

Ame no Uzume's meeting with Sarutahiko Okami when the 'heavenly kami' descended to meet 'the earthly kami'. (Photo from the ema of Tsubaki Shrine in Mie Prefecture)

***************************************

Jake Davis has some good photos of Otafuku, particularly of her sexual guise, at the following link…http://ojisanjake.blogspot.jp/2008/12/otafuku-mask.html

The Daruma museum by Gabi Greve also has a piece on Otafuku/Okame, including the intriguing Ofuku Daruma http://darumadollmuseum.blogspot.jp/2005/12/otafuku-daruma.html

Readers may be interested in the role of Okame in contemporary goddess worship; see http://journeyingtothegoddess.wordpress.com/2012/11/21/goddess-okame/#comments

Could you tell us about your background?

Could you tell us about your background?