This month’s Kansai Scene has an article that covers the Japanese way of dealing with death that provides a comprehensive overview of the subject – appropriate perhaps as we approach 3/11 (see previous post), though the article is timed to coincide with higan this month. Traditionally the spring and autumn equinox, as well as Obon, are seen as times of year when the veil between this world and the other is at its thinnest, prompting care of one’s ancestors with a memorial visit to the grave.

*************************************************

Text: Alan Wiren

Japanese funerals are an assimilation of Shinto philosophy, Buddhist formalities, and modern culture. The combination may be disturbing, even shocking, to the uninitiated. If you are called to take part in a Japanese funeral, the more you know beforehand, the better able you will be able to support and comfort those who are going through it with you. At the same time, experiencing this unfortunate, but inevitable event is an opportunity for a deep insight into the Japanese culture and psyche.

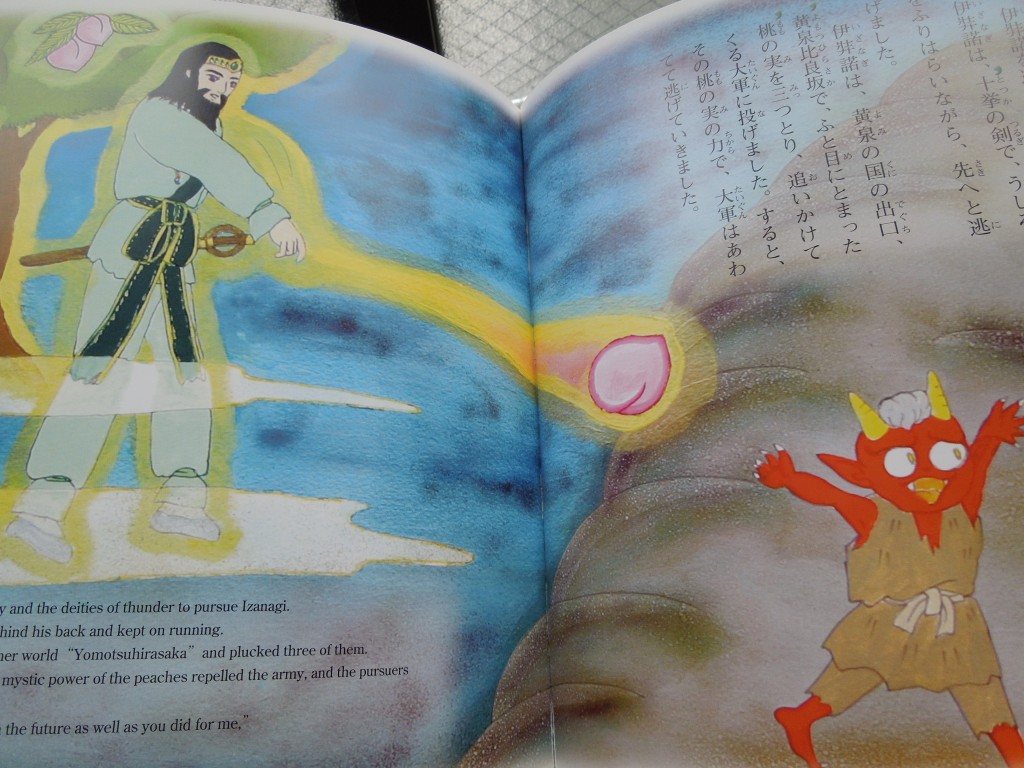

From time out of mind, Shinto tradition has had an answer to the perennial questions: ‘Where do we come from?’ and ‘Where do we go when we die?’ Japan’s agrarian society held that Nature’s greatest spirit would dwell in the mountains in winter and move to the fields in summer. Human spirits as well would come out from the mountain spirit to be born and, at the end of their lives, return to it. That philosophy dovetailed reasonably well with a Buddhist idea that would arrive later: the purpose of a funeral is to ease a soul’s transition from one life to the next.

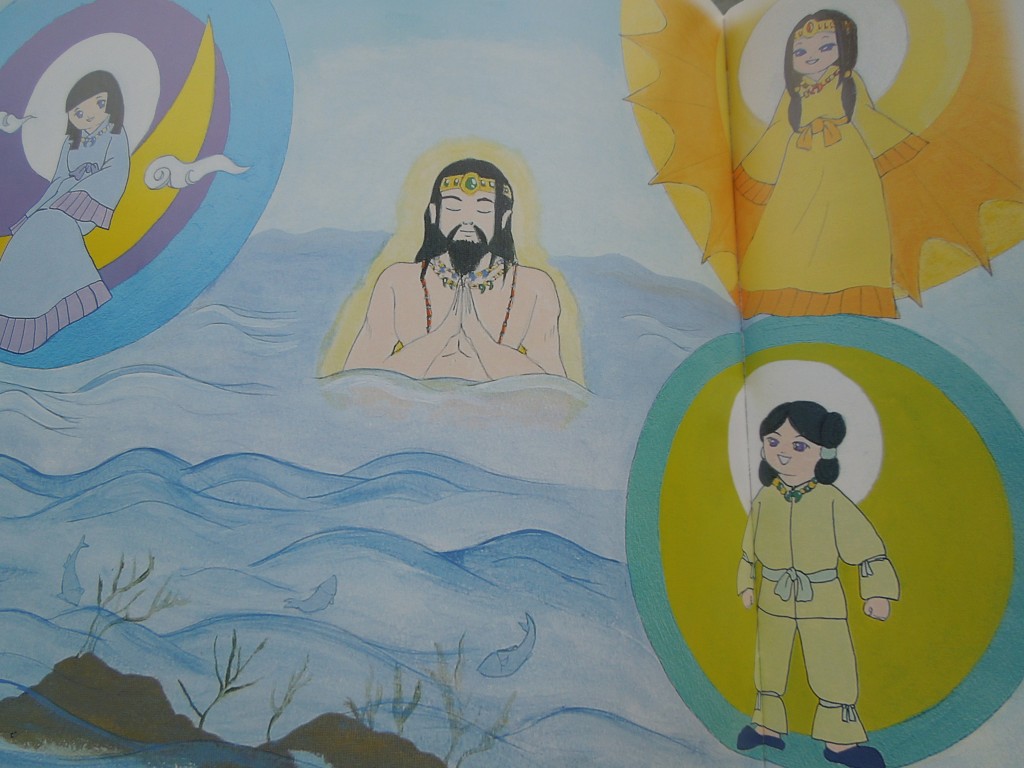

Enma, god of judgement in the afterworld. Note the circular mirror before him.

Buddhist funeral services were, at first, reserved for Buddhist priests, but between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries they began to be offered, first to the important patrons of temples, and then to common folk as the need for support grew among competing sects. Buddhist funeral rights and ancestor worship were all but taken for granted after 1638 when, in an effort to stamp out Christianity, all Japanese families were required to be registered with a Buddhist temple.

The rites begin nearly at the instant of death. If at all possible, the body of the deceased will rest for one final night at the home where he or she lived. A futon is made up with new sheets in a common area of the home. Men of the family may be asked to help place the body onto it. The body is then be packed with ice, and covered with a sheet. The face is covered with a smaller, white cloth.

Then a kind of informal wake begins. Members of the immediate family including children of all ages, relatives living close by, neighbors, anyone in the vicinity with a connection to the deceased will drop by to offer their condolences and to visit with the body. It is not uncommon for visitors to sit with, touch, and talk to the body as if it were still living. A priest from the deceased’s temple will be called in to offer a session of sutra reading and prayer.

The following morning the body will be moved to the place where formal services will be held. This may be a temple or a more secular facility. The body is usually carried in a hearse in a slow procession, demonstrating reluctance in bringing the body towards its end. At the destination the body is placed into a coffin and packed with dry ice. Once again, during this process the men of the family may be conscripted for lifting.

The formal wake begins when the coffin — which may be elaborately decorated or a plain, wooden box, but usually has a window in the cover, for viewing the body’s face — is placed in front of an arrangement of sculpture and ornament, adorned and surrounded with flowers, and lamps, to suggest Paradise. A black-framed portrait of the deceased is set within the arrangement. Incense is lighted and must be kept burning as long as the coffin is present.

Mortuary tablets

Guests attending the wake will bring with them envelopes containing money and bound with black and white string. The envelopes are available in most stationary stores and the appropriate amount of money is determined by the closeness of their relation to the deceased. The priest begins chanting a sutra. While he does, first the immediate family, including the spouse, children and grandchildren, and their spouses, then the guests, will, one by one, approach an alter that has been set in front of the coffin. They will transfer some granular incense to a burner, pray to and then bow to the portrait. The guests will finally bow to the immediate family, before returning to their seats. When everyone has performed the ritual, the wake is finished.

On the following day the funeral takes place. In form it is precisely the same as the wake, but the atmosphere is more formal. At the wake there may be warmth, smiles, and handshakes. At the funeral there is solemnity. The bows are more precise. Expressions are dour.

As soon as the funeral ends the flowers are taken from their arrangements and given to the family members. The coffin is opened and the flowers placed inside, around the body. After that the cover will be closed again, and may be nailed in place.

Next the coffin is brought to the crematorium. Although cremation has had a checkered history in Japan — it was legally banned in the nineteenth century when Buddhism suffered the same fate a Christianity in the seventeenth — it is now virtually universal. This is the last time that male strength may be conscripted. The coffin is placed into a furnace and the closest relative may have the responsibility of turning the fire on and off, although this is sometimes handled by the crematorium staff. While the fire burns, the family will adjourn for the funeral feast.

Funeral rites are marked by prayer and incense

When both the family and the flames have consumed their due, the family will assemble in a chamber where the slab bearing the deceased’s bones, and still radiating heat, is brought. The crematorium staff will usually give a short guided tour of the skeleton. In particular showing the hyoid bone from the neck, which seems to have a figure of a seated Buddha within. Then family members from toddlers to the aged will take up chopsticks, one bamboo and one willow to signify the physical and the spiritual worlds, and transfer bones from the slab to an urn. Mothers may encourage their children to take bones from the head to foster their intelligence. Others may take up certain bones to combat illness or injury.

All of this is just the beginning. Buddhism holds that the soul remains in the world of the living for seven days and can benefit from prayers and remembrance for even decades to follow. So Buddhism prescribes memorial services every day for the first seven days after the funeral, then once a week until the 49th day, one on the 100th day, and then one every year until the 50th year.

In Japan this schedule is varied to accommodate travel costs and cultural traditions. The first seven services may be replaced by one, following the cremation, but those on the first and third anniversary are sure not to be missed. They comprise the same ritual of incense burning and prayer, conducted in the family’s home.

The other annual memorials are commonly replaced with holiday observances. The Japanese calendar reflects the Buddhist idea that Paradise is in the west. The equinoxes, one this month, the other in September, when the sun sets directly in the west, are national holidays to allow families visit the graves of their ancestors. The period in mid August, called Obon, however, has become the occasion when most Japanese families gather to welcome the spirits of their ancestors for a few days.

Kyoto cemetery at the time of Obon, when lanterns are put out to welcome spirits back

Nakanishi performed just such a ceremony on Wednesday (Feb. 29) at Georgetown University’s Berkley Center for Religion, Peace and World Affairs during a program on the “Shinto response” to the disaster.

Nakanishi performed just such a ceremony on Wednesday (Feb. 29) at Georgetown University’s Berkley Center for Religion, Peace and World Affairs during a program on the “Shinto response” to the disaster.