I’ve long been an admirer of the writings of Michael Hoffman, “special to the Japan Times”. He has an enviable ability to condense and clarify arcane matters in lucid terms. In an article from 2009 I’ve just come across he gives a lengthy but insightful overview of Japan’s Rising Sun emblem. It’s packed with useful information, and for those without the time or inclination to read through it all there’s a summary of key points and quotations below. (For the full article, click here.)

* The present emperor underwent a ceremony affirming his connection with the sun goddess, Amaterasu. He’s claimed to be the 125th descendant in direct line from her.

* The Rock Cave myth, central to Shinto, is funny and playful in a way characteristic of Japanese culture

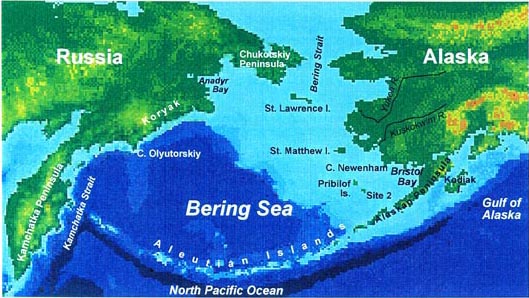

* Worship of a sun goddess was probably initiated by Ise fishermen, according to an article in The Cambridge History of Japan.

Opening the door of Amaterasu's cave

* The imperial clan orignally worshipped Takamimusubi. Contact with Korea motivated them to turn to the sun sometime in or after the fourth century. They looked to Ise, already a focus of sun worship and located in the direction of the rising sun. It led to the championing of a putative ancestor called Amaterasu (literally, Heavenly Shining One).

* Prince Shotoku (572-622) was the first Yamato leader to title himself “sovereign of the land of the rising sun”. The country’s name subsequently changed from Wa, or Daiwa, to Nihon, also read as Nippon (literally, sun source).

* First use of the rising sun flag was supposedly by the nationalist Buddhist priest Nichiren, who presented the shogun with a banner of a red sun against a white background at the time of the attempted Mongol invasion in 1274.

* The banner was subsequently used by various feudal lords and later by Hideyoshi when invading Korea.

* Nativist scholars of the eighteenth century rediscovered and championed Amaterasu. “The august imperial country (Japan) is the august country in which the awesome august divine ancestor Amaterasu Omikami came into being. The reason this country is superior to all other countries is, first and foremost, apparent from this fact,” wrote Motoori Norinaga.

* “Atsutane,” sums up the historian Goodman, “pointed to the remarkable coincidence of the centrality of the sun in the Copernican system and the central role of the Sun Goddess, Amaterasu Omikami, in the Shinto tradition, going so far as to suggest that heliocentricity may in fact have originated in Japan.”

* In 1870 the Meiji government made the Hinomaru the official flag of Japan as part of its ideology of putting the emperor at the centre of the nation’s affairs. It remains so to this day, and Amaterasu is still unofficially the emperor’s ancestor and Shinto’s supreme deity worshipped at Ise Jingu.

Sunrise and shimenawa: what could be more Japanese?